South Africa's corruption-buster stands her ground

- Published

Thuli Madonsela is surprised to be fighting the government in court

She speaks in the hushed, unthreatening tones of a primary school teacher explaining a bad school report to some indignant parents.

But Thuli Madonsela's conciliatory demeanour is misleading.

As South Africa's chief corruption-buster - officially known as the Public Protector - the dignified 51-year-old lawyer has earned a reputation for ferocious resolve in a country increasingly swamped by allegations of official graft.

And right now Ms Madonsela's resolve is being tested like never before.

"Things have just turned in a strange way," as she put it this week, with typical understatement, facing the cameras at a crowded news conference in Pretoria.

"Not in my wildest dreams did I think we'd end up in court."

For months, the Public Protector has been investigating the government's decision to spend 206m rand ($20m; £12m) of taxpayers' money on "security upgrades" for President Jacob Zuma's private rural home in a village called Nkandla - a home not used for any official state functions.

The spectacularly lavish renovations, external - I've driven past the hillside complex which now resembles a rather grand country club - have provoked some outrage here.

So have the increasingly robust efforts of the state to bury, block or generally sidestep any final public reckoning on the issue of exactly who paid whom for what.

The chalets and refurbishments at Nkandla are said to have cost $20m (£12m)

President Zuma has repeatedly insisted that he paid for the renovations himself and that the security upgrades - which reportedly include underground tunnels and a bunker - were a separate matter.

Earlier this month, after many delays, the Public Protector prepared to release her own forensic analysis of what has, inevitably, been dubbed Nkandla-gate.

At which point President Zuma's closest aides leapt to his defence, rushing to present Ms Madonsela with notice of a court action to block the draft report's release, on the grounds that the president's domestic security might be compromised.

"Did they really just say that?" Ms Madonsela asked, remembering the astonishment of her team when the court papers arrived. "Our report was prepared with extreme care to avoid any security breaches.

"It's a straightforward investigation. We're a friend to government when we conduct [our investigations] because we show how money can be clawed back."

Then, with a demure smile, she slipped in the knife: "Perhaps people speak fast and don't have the opportunity to read [the relevant documents]. Ministers have never cited any constitutional or statutory provision that gives them the rights they claim in the court papers."

If this were merely a squabble about what sort of bulletproof glass Mr Zuma has in his living room, and whether he'd be safer if the matter were kept private, then perhaps we could dismiss it as such.

No fear

But there is reason to believe that more is at stake for South Africa and its democratic institutions.

Critics of the president - a growing crowd these days - point back to 2009, and the unexpected emergence of a wiretap that suggested there was political meddling in a corruption case against Mr Zuma.

The case was promptly dropped, allowing Mr Zuma to become South Africa's president a few months later.

At issue then, and now, is not so much the issue of Mr Zuma's innocence or guilt. We should, presumably, assume the former.

Rather it is the danger that South Africa's young institutions - the prosecuting authority, the state intelligence services, the public protector's office and so on - are being weakened by political forces anxious to protect individuals from legitimate scrutiny.

"I don't really fear for my job," said Ms Madonsela, after being asked about newspaper reports that she was being threatened with arrest. "I can't really know how safe I am. I'm not a security expert."

At this point it is worth mentioning that South Africa is in full pre-election mode, so every issue and every conflict takes on a particularly shrill tone.

After all, the Nkandla scandal - however it plays out - seems unlikely to win the governing African National Congress too many votes.

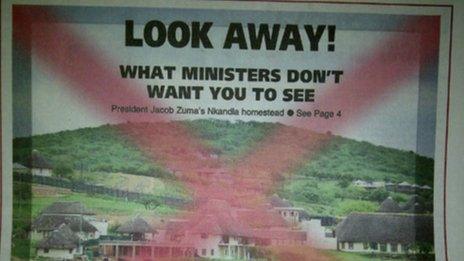

But electioneering alone cannot explain the latest moves by South Africa's security ministers, who are now vigorously warning the media that they will be prosecuted if they dare to publish any close-up images of Nkandla. The threat has provoked a robust "So, arrest us", external headline from one local newspaper.

But it has also fed into a growing sense that, after 20 years of democracy, the lines between the state, the government, and the ANC are becoming increasingly blurred - at least in the eyes of some of those in power.

For now, Ms Madonsela is holding her ground and trying, as she put it, to "depoliticise" her report.

A nice, gentle-sounding word. But as usual it hides a more formidable intention - to ensure that the security ministers to whom she had given an early copy of the report (something she now admits was a mistake) are now kept out of the loop.

She says she'll take note of their concerns, and consult with technical experts from within government and, if necessary, outside it.

But no-one outside her small team will see the full report until she releases a draft, "in a manner I deem fit," perhaps in "a month from now."

"This is where we begin the healing… now we have the task of rebuilding trust," she said, flashing another disarming smile and noting that in the past she had sought to avoid conflicts by "whispering" to relevant government officials.

The time for whispers, Ms Madonsela seemed to be implying, may now be over.

- Published22 November 2013

- Published6 April 2018

- Published19 December 2012

- Published9 July 2024