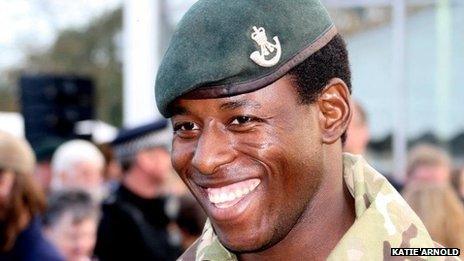

Paul Apowida: From Ghanaian 'spirit boy' to UK soldier

- Published

The so called "spirit children" are said to typically be born with physical disabilities or identified as being the cause of misfortune

Paul Apowida is a soldier and accomplished painter whose first book has just been published.

But his life - which has been so rich and varied - was nearly snuffed out soon after it began.

Attempts were made to kill him as a baby because he was labelled a "spirit child" - a youngster possessed by an evil force.

The conclusion was drawn because Apowida's parents and six other relatives died suddenly soon after his birth in Sirigu, a rural town in northern Ghana, near the border with Burkina Faso.

So-called spirit children are typically born with physical disabilities or identified as being the cause of misfortune, as in Apowida's case.

The attempts on his life, his formative years growing up in an orphanage and his return as an adult to Sirigu form the basis of his book, Spirit Boy.

"All they think is that when a child is born and has deformities, or things start happening, is that the child is evil," he told the BBC.

"I wrote this book to show there's no such thing as a spirit boy. I wouldn't have done so many good things if I was evil."

It is nearly 30 years since attempts were made to poison Apowida.

He was fortunate enough to be saved by a local nun who moved him to an orphanage hundreds of miles away, in southern Ghana.

After a stint at an art college in the capital, Accra, he joined the British army and has served in Afghanistan.

'Deformities reversed'

He is one of the few "spirit children" able to progress to adult life.

But the practice of killing youngsters continued in Sirigu long after he was moved from the town.

To locals, the town has become synonymous with infanticide.

These children were accused of being "spirit children"

However, the killing of spirit children is an established practice across the Kasena-Nankana district of Ghana's Upper East region.

Six months ago, local leaders in northern Ghana announced the abolition of the ritual killings across seven towns in the region.

They said anyone caught trying to harm children would be handed over to the police.

The "concoction men" who used to give poisonous drinks to children have been given new roles.

Working in partnership with UK campaign group Afrikids, they agreed to work with disabled children to promote their rights.

It is the culmination of a relationship built between the charity and the local community over the last decade.

But, half a year on from the announcement of the ban, what has changed?

Afrikids says there have been no recorded instances of infanticide for the last three years.

Raymond Ayine, from the group, said awareness campaigns led by the group, as well as improved access to education, now mean more people understand that physical disabilities have a medical explanation.

"There are a number of children for whom we funded medical operations. Some of their deformities were reversed after surgery.

"They are living and the community now says if they were spirit children, they would have died. The longer they live, the more they are accepted."

Similarly, local chief Naba Adumbire Akwara said the "traditional methods of killing and dumping spirit children are a thing of the past" in Sirigu.

Ghana's constitution prohibits all forms of harmful cultural practices. But, in reality, little has been done by police over the years to end the practice.

The only recorded arrest of concoction men took place after an investigative journalist claimed a baby was killed in Sirigu early this year.

The apparent shift has been welcomed by Ghana's Minister of Gender, Children and Social Protection, Nana Oye Lithur.

'Fetish priests'

"We are happy to hear that the practice of killing spirit children no longer exists in these districts," she said in September.

"What is even more significant is the involvement of the practitioners of the tradition known as concoction men in the solution process," she added.

However, there is no way to prove that the practice is not continuing secretly.

Paul Apowida was deployed to Afghanistan

Attitudes are hard to change, as Angela Aposelse found out when she gave birth to a child who had no legs.

"My husband insisted the child is a spirit child and wanted to kill her, so the midwife contacted Afrikids who initially took custody of the child," she said.

"When I got my child, every night my husband and his people tried to kill her, but I stayed awake.

"It's been three years now. My husband still doesn't love the child. My neighbours also mock me that my child is not able to walk and has no future. But she is my child and God gave her to me," Ms Aposelse said.

Despite such stories, anecdotal evidence suggests attitudes are shifting.

In Sirigu, children were killed by herbalists - called concoction men - and the dead body would be taken to the top of a hill in a wooded area known locally as the Evil Forest.

The bodies were dumped in shallow graves, covered by stones. Pregnant women were not permitted to visit the forest, amid fears that an evil spirit would possess their unborn child.

But the BBC's Sammy Darko, reporting from Sirigu, says women have begun to visit the area to pick fruit and gather firewood.

However, our correspondent says the situation in Sirigu is not reflected in other towns in the Kasena-Nankana district.

In the town of Bongo, about an hour's drive from Sirigu, the paramount chief of the area - Bonaba Lemyaarum Baba Salifu Atamale - told our correspondent that the killings had not stopped.

"In my community they don't have a place where they take them to, but they kill them, the fetish priests are the ones who kill them, the families approach them and they come secretly and get rid of them, so if you are not in the know it's difficult to apprehend them."

Back in London, Apowida is planning his next journey to the town he still calls home.

During his most recent visit to Sirigu in 2011, he spoke to concoction men who were responsible for the deaths of countless children over the years.

"What they told me was that it wasn't their fault. It was the family members who brought the babies for them to kill."

He said the move to involve concoction men and give them alternative forms of income has been instrumental in helping to curb the practice in Sirigu.

And, when asked how prevalent he thinks the practice remains in the part of northern Ghana he hails from, he is adamant that the plight of youngsters earmarked as evil must not be forgotten or ignored.

"It's still going on. There's still more work to be done," he said.

- Published29 April 2013

- Published1 September 2012

- Published2 March 2012