Nelson Mandela death: Soweto's sorrow

- Published

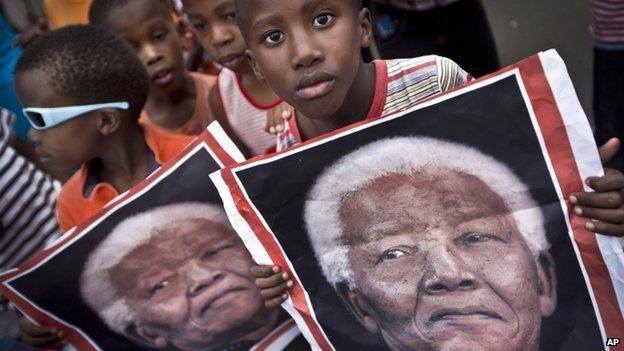

Scenes of celebration of Nelson Mandela's life in Soweto

Nelson Mandela, South Africa's anti-apartheid icon, was not afraid to die.

For years his people have been fearful of losing him, but he had shown South Africans a number of times that he did not fear death; perhaps the many times he fought back from his hospital bed showed that he was not ready to leave them - such was his love for his people.

Now South Africans have a chance to return some of that love.

Hundreds upon hundreds have gathered at his homes in Johannesburg - his current one in the northern suburb of Houghton and the house where he lived in Soweto before his imprisonment - to pay their respects to the nation's first black and democratically elected president, the man, seen as a terrorist by some, turned the world's most-loved statesman.

Crowds of black and white people, interracial couples and children are standing side by side outside his old home in Orlando West, Soweto - singing struggle songs in his memory, a fitting tribute to the man who spent 27 years in prison so black and white South Africans could live as equals.

Vilakazi Street is filled with the sound of stomping feet, chanting and ululating.

Children are carrying posters of Mr Mandela and some local taxis have pasted his face on their windows.

A hundred or so people from neighbouring townships had gathered from as early at 07:00 local time (05:00 GMT) but by midday the crowd had swelled and had become more diverse from all parts of the province of Gauteng.

Some of the first to pay their respects were three elderly women, two of whom walked using canes, slowly making their way to the entrance of the Mandela house, now a museum.

'Shocked'

I asked where they were going, and their answer was short, direct and painful: "Siyogxwala emswaneni".

It is a Xhosa phrase which means "we are going to comfort the family of the deceased".

In African culture people gather at the home of the deceased, and although their visit is symbolic as the Mandela family no longer lives here, it is felt it is a place where his spirit dwelt at some point.

It is a sign of respect to the person who has died but also to a message of comfort to the family he leaves behind.

The statement also has a deeper hidden meaning - a realisation that what is done is done and we cannot change it, a painful call to acceptance.

"It is always sad to lose someone you love," says Tshepo Lebepe, 48, a businessman from the town of Alberton, outside Johannesburg.

"But I am also overcome by a sense of relief. He was frail and sick and at least now I know that he is resting.

"We need to honour him by continuing where he left off."

However, for many his death has still not sunk in.

As a black South African born as apartheid was coming to an end, it feels to me like an out of body experience, like deja-vu from a vivid dream.

My mind can scarcely comprehend that he is indeed gone - that a man as great as him, merely shut his eyes, never to open them again.

Palesa Motaung, who was seven years old when Mr Mandela was released from prison in 1990, agrees.

"We've always known him as a fighter.

"As young children growing up in the township we knew that there was this Mandela fighting for our freedom but we are shocked that he is gone. Shocked."

His strength made many here forget, even if only for a short while, that he was mortal, that with each health scare he would soon have to let go.

Mandela's name illegal

When black South Africans mourn they do it through song, through dance.

Today people are singing struggle songs in the heart of Soweto, which was once the scene of brutal killings and assaults at the height of white oppression.

Some are reminded of a time when even the mere mention of Mr Mandela's name was illegal.

"When Mandela came out prison he insisted on visiting all his neighbours, I was fortunate to accompany him on these visits," said Shadrack Motau, 69, who lives a few houses away from the Mandela house.

"Some people tried to turn him away because they were not sure about him but in the end he won all of them over. I will miss his humility."

And why did people love him so much?

He was not just a world icon, but a father, a grandfather, a husband and to many South Africans he represented the best of what black people could be, the best of what white people could be.

Black and white alike called him "Tata" - meaning father and that is what most people will remember him as, the father of the nation

"He wasn't perfect but his love for justice, for the truth, for peace was honest," said Chantal Smith, from the affluent suburb of Sandton in Johannesburg.

What was apartheid? A 90-second look back at decades of injustice

It is remarkable that a man who had spent almost three decades oppressed because of the colour of his skin and commanded the support of millions of angry black people - capable of bringing this country to its knees at his say so - could come out of prison and instead preach peace and forgiveness.

"This country does not know the deep gratitude it owes to Tata Mandela," said Richard Nhlapho, 44, from the Johannesburg suburb of Mondeor not far from Soweto.

"Just look at the people here, the different races. Who would have thought this would every happen here?"

As the dust settles and many begin to accept that this is the end of an era, South Africans and indeed all Africans will be hoping that the spirit of unity he engendered will on.

And that his "Madiba magic" will carry the country into its next chapter - a chapter to hopefully make Mr Mandela proud.