Mandela remembered in Terreblanche stronghold

- Published

"Madiba's death caused pain in my heart... I feel empty without him"

In the home town of South Africa's late white supremacist leader Eugene Terreblanche, the BBC's Fergal Keane finds people publicly mourning for Nelson Mandela.

On a hot still day in the southern summer, Ventersdorp can seem a forlorn place.

The poor of the town beg at shop entrances or ask for a few rand as they direct cars into parking spaces.

To somebody who knew the town in the old days of white supremacy, what is striking is that the beggars are both black and white.

They compete for the compassion of shoppers.

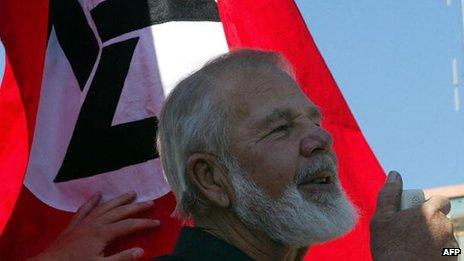

Eugene Terreblanche was always vocal in his opposition to Nelson Mandela

Two hours west of Johannesburg on the platteland (literally the "flatlands"), Ventersdorp was once notorious as the headquarters of white extremism in South Africa.

The neo-Nazi AWB - Afrikaner Resistance Movement - and its leader, Eugene Terreblanche, were based here.

Journalists would regularly drive there to hear Terreblanche fulminate against Nelson Mandela and threaten to "trample the ANC into the gravel".

It was here on the night of 9 August 1991 that I witnessed a fatal clash between the AWB and the police, the first time in apartheid history that state security forces opened fire on white extremists.

Three right-wingers and a passer-by were killed. A black family was surrounded and attacked in a minibus and terrorised.

After that, Ventersdorp sat in my memory as a place of fear.

But today, the AWB is fractured and irrelevant and Ventersdorp town council is governed by the African National Congress.

Eugene Terreblanche is dead, murdered by a farm worker three years ago.

No climate of fear

Black South Africans no longer walk the streets as subservient beings.

For black resident Nick Bergman, destroying the climate of fear was Mr Mandela's greatest legacy.

Like the rest of the town's black residents we met, he feels bereft at the ANC leader's passing: "Madiba has done so much. I can't even tell you in words.

"The thing I can tell you is that his death has caused pain in my heart… I feel empty without him."

But for all the change of the last 20 years, Ventersdorp was the one place in all of South Africa where I struggled to imagine Afrikaners publicly mourning the death of Mr Mandela.

I was wrong. At the Dutch Reformed Church on Cochrane Street, I watched the old and the young stand in silence to remember Mr Mandela.

The pastor, Gerrit Strydom, served as a soldier patrolling the black townships during the violence of the transition years.

The Dutch Reformed Church provided a religious justification for apartheid; its ministers once preached that blacks were inferior beings, the "hewers of wood and drawers of water" of the Book of Joshua in the Old Testament.

The congregation at the Dutch Reformed Church remembered Mr Mandela

Mr Strydom believes Mr Mandela taught Afrikaners the value of reconciliation.

"After all the years we had him in prison, he could have turned around and made South Africa a bad place for our people.

"But Nelson Mandela was the one guy who brought people together."

Anxiety over future

However, it would be foolish to imagine that Ventersdorp has evolved into a paradise of racial harmony.

Most farms in the area are owned by white people...

.. who employ black labourers

Given the centuries of bloody history and the trauma of the recent past, there is still much that divides black and white people in the area.

In many respects, the rhythms of rural life have hardly changed.

On the farms it is still the whites who own the best land and the black people who work as their labourers and servants.

White farmers repeatedly speak of the fear of being attacked on their property.

Even among white farmers who respect Mr Mandela, there is anxiety about the future and a burgeoning sense of grievance at perceived discrimination against white people.

On his 730-acre (295-hectare) farm outside Ventersdorp, Derrick Allem says he has stayed in South Africa because Mr Mandela gave him faith in the future of the country.

But he has little faith in the new generation of leaders.

"I think what he [Mr Mandela] wanted was for everybody to have opportunities, and a good and fair life for everybody.

"I don't think he wanted to suppress. That is what he said. No nation should suppress another nation, no matter their colour.

"So I think what's happening now is reverse apartheid.

"The whites are being suppressed now by the blacks."

Flimsy shacks

This is not an argument that finds any sympathy in the black settlement of Goedegevonden next to Mr Allem's farm.

Back in 1991, this was a desolate collection of shacks attacked by the AWB who were determined to drive out the black residents.

They failed.

The logic of numbers and the speed of the transition to democracy undid extremist plans.

Although new brick-built houses rise amid the shacks, poverty and inequality remain acute.

Here the complaint, backed up by public protest, has been that the government is failing to deliver on basic services for the black majority.

Elderly resident Anna Johnson lives with her two grandchildren in a tiny shack made of corrugated iron.

"I feel sick. The thing that is worst is that I need a house.

"I get wet from the rain. When it rains it floods in here."

I noticed that on one of the flimsy walls there were two paintings: one of Jesus Christ, the other of Nelson Mandela.

Driving away from Ventersdorp, I reflected that among black and white, he is the one figure here who seems to stand above criticism.

As Ms Johnson says: "What he gave us was beyond what we expected.

"We were in chains, he freed us. We were blind and he opened our eyes."