Post-Mandela South Africa is in good shape

- Published

Nelson Mandela's coffin is taken to his final resting place in Qunu by a military guard of honour

The South African writer Andre Brink, an Afrikaner who defied apartheid, once wrote of his country as a place where thoughts for the future demanded that fear be set aside, however difficult that might be. "Such a long journey ahead," he wrote, is "not a question of imagination but of faith".

I thought of his words repeatedly as I drove through South Africa over the last week.

From the farmlands of the platteland in the west to the mist-covered hills of the Eastern Cape.

For at the end of this momentous week the question is no longer how far South Africa has travelled since the days of apartheid but of the country that lies ahead.

But first a few memories of a journey.

In the passport queue in Johannesburg, it felt like every journalist in the world was waiting to be stamped through.

We joined tourists heading here for the southern summer and South Africans coming back for Christmas.

Driving into the city, past the familiar landscape of old mine dumps huddled around the tall buildings of downtown, I switched on the car radio.

A boy carries newspapers in Nelson Mandela's home village of Qunu

Voices were calling in from around the country expressing sadness, but there was no sense of shock.

After all, this was a death long foretold, through several scares in the past year, as Mr Mandela's recurring lung infection wore down his strength.

What was most pervasive was the sense that a guiding moral presence had been removed.

Caller after caller spoke of Mr Mandela as "Tata" - the father of the nation.

South Africans are nostalgic for leaders who were seen as being incorruptible and generous in spirit.

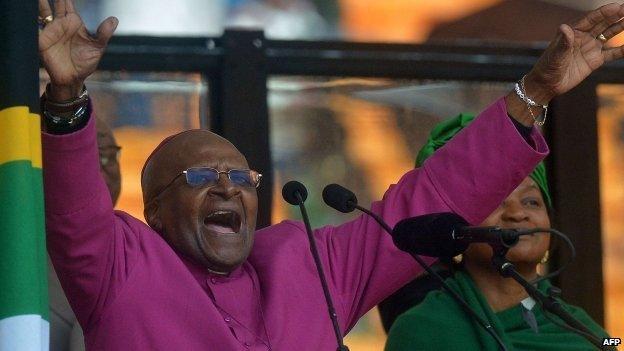

The era of African National Congress (ANC) icons, that included Mr Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Oliver Tambo and others who had come to prominence in the post-World War Two era, has come to a close. Only Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu, remains, and he has largely stepped back from public life.

Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu was a visible opponent of apartheid when Nelson Mandela was in jail

Throughout the journey of the last week, I have encountered people in all walks of life who have first expressed grief and then uncertainty about the political future.

Nobody I met believed the stories peddled on the internet and the less thoughtful elements of the press about chaos after Mr Mandela.

Such spasms of panic have long accompanied periods of change here.

Their opposite is the myth of a Rainbow Nation where good triumphed over evil and the united people walk hand-in-hand into the future.

These competing narratives obscure the complex truths of the country that Mr Mandela has left behind.

And what has been obscured by the events of the last week is that, politically, South Africa has already moved beyond Mandela.

It is a messy, troubled, inspiring, hopeful, frustrating, vibrant democracy. And many more things besides.

The country is far more stable than it is often given credit for.

This has a great deal to do with the power of civil society, the tradition of a free press and the rule of law.

All have faced pressure in the last two decades but remain robust defenders of democracy.

Apartheid repression created the conditions in which people moved to protest in a wide variety of ways.

Despite a whole array of repressive legislation, it did not destroy the institutions upon which free speech is based. The often fractious voice of opposition is thriving.

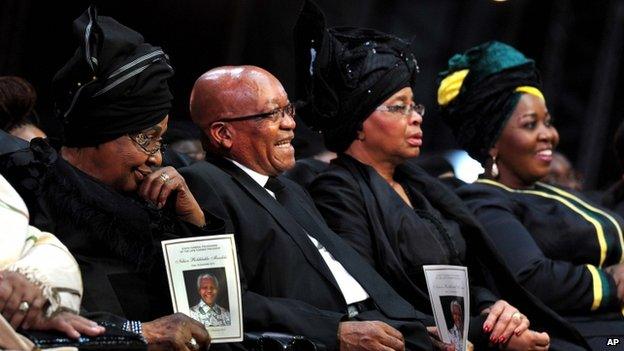

President Jacob Zuma discovered this at the memorial service in Soweto where he was booed.

The government is furious at this open show of disrespect for the president.

President Zuma sat between Mr Mandela's ex-wife Winnie and his widow Graca Machel (2nd R) at the funeral

Some of those I have spoken with along the road felt pain that a solemn moment in the life of the nation had been disrupted by the bitterness of contemporary politics.

But I also met many who felt the current president was reaping a whirlwind he and the rest of the ruling elite had sown for themselves.

There is deep public disillusionment over official corruption and the perception that the riches of the nation are still the property of a few.

From farmlands to the townships, I have heard criticism of the government.

None of this means the writing is on the wall for the ANC.

There will be a loss of support, perhaps a substantial one, in elections due early next year. But loss of power seems a way off yet.

Leaving South Africa at the end of this momentous week, my mind went back to two singular points in a longer personal journey here.

The first was 1986 at the height of the State of Emergency under apartheid rule. Then, I felt despair for the future. Bloody racial conflict seemed inevitable. Time proved me wrong.

The second memory is of the day Mr Mandela was inaugurated as president in 1994.

Standing on the steps of the Union Buildings in Pretoria, hearing him sworn in as president, I felt a surge of optimism for the future.

I am still hopeful. Not in a misty-eyed, unrealistic way. But the voices of the last week - always passionate, often dissenting - had in common a deep love for their country. That is a legacy Mr Mandela would be proud of.