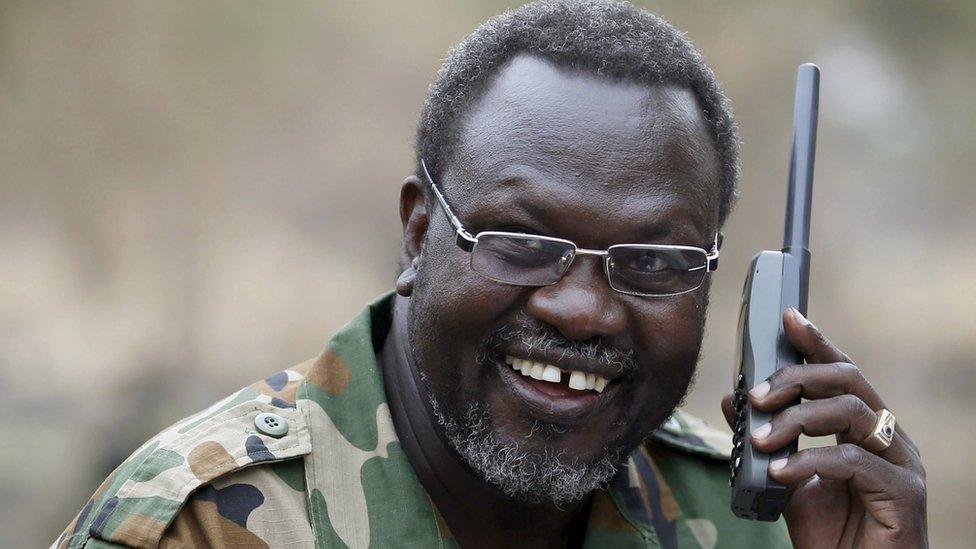

Riek Machar: South Sudan warlord turned peacemaker?

- Published

Riek Machar is a man who wears many labels: rebel leader, former vice-president, warlord and now, possibly, peacemaker.

Emerging from enforced isolation in South Africa, Mr Machar, a central figure in Sudanese and South Sudanese politics for decades, and his bitter river Salva Kiir are expected to hold a meeting which could mark the beginning of the end for a conflict which has torn the world's youngest country apart for five years.

But South Sudan - and Mr Machar - have been here before. A peace deal signed in 2015 resulted in him returning to the capital, Juba, to take up a new post in the unity government, only to flee months later as fighting escalated once more.

So who is this man apparently holding the fate of a nation in his hands?

'Warlord'

Mr Machar is reputed to be a wily operator, switching sides on several occasions during the long north-south conflict as he sought to strengthen his own position and that of his Nuer ethnic group in the murky political waters of Sudan, and later South Sudan.

Things could have been quite different. In the mid-1980s, Mr Machar gained a PhD in philosophy and strategic planning from the University of Bradford.

But at the same time, things were changing in his home country. It was a time of political revolt, with the Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) having just been formed to campaign against northern rule.

Mr Machar chose to join the fight - and has never looked back.

Many are hoping that foreign governments will help rebuild the country

In 1991, he married British aid worker Emma McCune, who died two years later, while pregnant, in a car accident in the Kenyan capital, Nairobi.

She was dubbed by some in the media as the "warlord's wife", a reference to Mr Machar's role as a leading commander in the armed wing of the SPLM, which was then spearheading the war for South Sudan's independence from the north.

After a peace deal was signed in 2005 to herald the end of that conflict, and the sudden death of its leader John Garang, the SPLM appointed Mr Machar as the vice-president of the regional South Sudanese government.

In a sign of the enormous influence he wielded, Mr Machar retained the post after South Sudan became independent in 2011 until his dismissal in 2013.

'Immense patience'

Coming from South Sudan's second largest ethnic group, the gap-toothed Mr Machar's presence in the upper echelons of power was seen as vital to promote ethnic unity with the Dinka majority.

Mr Kiir's forces clashed with Mr Machar's fighters in the world's youngest state

Recalling meeting him in 2005, BBC Africa's David Amanor said he had a commanding physique.

"He's got a steely but also gentle look. He's well-spoken and well-educated," he said.

At the time, Mr Machar had swapped his military fatigue for an English suit, playing the role of a mediator between the Ugandan government and the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) rebel movement.

He saw the LRA as a major threat, believing that it could destabilise South Sudan, where it had military camps.

More on South Sudan:

Inside South Sudan's civil war

Although the peace initiative failed, Mr Machar - now married to South Sudanese politician Angelina Teny - was impressive as a mediator.

"He showed immense patience - the skills of a diplomat," recalled Mr Amanor, who covered the talks.

'Prophet of doom'

But critics say he also showed his ruthless side when he backed government forces in their fight against prominent South Sudan rebel leader George Athor, who was accused of waging a new "proxy war" on behalf of the Khartoum government, which it denied.

In December 2011 - some five months after independence - Mr Machar announced that Mr Athor had been killed near the Sudan-South Sudan border.

Riek Machar: At a glance

Studied at UK's University of Bradford, obtaining a PhD in philosophy and strategic planning in 1984

Married UK aid worker Emma McCune in 1991; she died while pregnant

Switched sides on several occasions during the north-south conflict as he sought to strengthen his position and that of his Nuer ethnic group

Sacked as South Sudan's vice-president in July 2013

Denied he was plotting a coup in December 2013 - but his fallout with President Kiir led to more than two years of conflict

Sworn in again as vice-president in April 2016 as part of an internationally brokered peace deal

Fled into DR Congo after fighting resumed in July 2016, before going to South Africa

Critics in the SPLM believed Mr Machar was becoming too powerful when President Kiir sacked him from the government in 2013.

Mr Kiir labelled him as a "prophet of doom", continuing his actions of the past - an apparent reference to the fact that he had challenged the authority of Mr Garang, the SPLM's founding leader, in the early 1990s.

That challenge resulted in Mr Machar forming a breakaway rebel group, eventually signing his own peace accord with Sudan's Omar al-Bashir's government in 1997, before becoming an assistant to the president.

Even after he left to re-launch a rebellion, Mr Garang's SPLM remained deeply suspicious of him, accusing him of receiving covert support from the Khartoum government - a charge he denied.

Destruction

Then, not long after he sacked Mr Machar, President Kiir accused him of plotting a coup, which prompted him to flee the capital, Juba.

Mr Machar denied the allegation, but it triggered a civil war which killed tens of thousands of people and left some two million homeless.

The vice-president is currently married to South Sudanese politician Angelina Teny

It was hoped the war was finally drawing to a close when a peace deal was agreed between the two men in August 2015.

In April the following year, after protracted negotiations by regional mediators, Mr Machar was sworn in once more, promising to rebuild his country.

It wasn't to be: Mr Machar fled South Sudan in July of that year, crossing the border into the Democratic Republic of Congo with hundreds of loyal followers.

From there, he moved to the Sudanese capital, Khartoum, and then to South Africa, where he was kept isolated at a farmhouse near Johannesburg until he was allowed to leave to travel to Ethiopia in June 2018 for renewed peace talks.

What will come of this meeting with his old rival remains to be seen. However, if they are successful, Mr Machar will hope to once again move from rebel to vice-president.

- Published18 April 2023