Analysis: South Sudan's bitter divide

- Published

Despite numerous personal difficulties, David says that he has no regrets about South Sudan winning its independence

Despite calls for a ceasefire and peace talks, fighting is continuing in South Sudan, the world's newest state. From the capital Juba, the BBC's James Copnall reports on the background to the conflict.

In the middle of a new camp for the scared and the desperate, made up of hundreds of makeshift shelters clustered around a road, I saw a familiar face.

When I first interviewed David in 2011, he was in Khartoum.

A southern Sudanese, he had fled the fighting in his home area, and was living in what was then still the capital of the united Sudan.

At the time he was planning to go back home, to celebrate South Sudan's upcoming independence.

A few months later, we met again in Juba.

Life was hard, he said. There were not many jobs. But the euphoria of independence still glowed strong, whatever the challenges.

Now David is displaced in his own country, one of tens of thousands seeking shelter at a UN base to escape the fighting which is devastating South Sudan.

Military impulse

The implosion has happened incredibly quickly.

Thousands of people have been displaced in the latest bout of fighting

The clashes began on 15 December in the capital Juba, and within days spread to several other places around the country.

The problems have deep roots. Some of them can be found in David's own story.

At independence, South Sudan was extremely fragile.

The new country had suffered through decades of conflict with Khartoum.

South Sudan's leaders are all former rebels, and the step from a political problem to a military response is one that is made far too easily here.

Those former rebels had also often fought each other, most notably after Riek Machar and others split away from the main rebel group, the Sudan People's Liberation Army/Movement (SPLA/M), in 1991.

Ethnic nepotism

The war also deepened ethnic tensions, in part because Khartoum armed some ethnic groups against others.

At separation, South Sudan was one of the least developed places on Earth, the result of decades of neglect and the long war years.

Millions like David had fled their homes.

Any government would have struggled to overcome these sort of challenges.

However, South Sudan's political class has failed the people.

Corruption is widespread, as is regional and ethnic nepotism.

This is what David, and many others, were complaining about after independence.

In addition, a political rift within the SPLM grew wider.

President Salva Kiir and his deputy, Mr Machar, who had been on opposite sides of the 1991 split, grew more and more antagonistic.

In time, other influential figures, including ministers and SPLM Secretary General Pagan Amum also began to criticise the president.

South Sudan's politicians need to forge a genuine national identity, which puts the national interest first

He was accused of sacking state governors unconstitutionally, quashing dissent in the party and not allowing a democratic challenge to his rule.

"You can't ignore the ethnic dimension in all this," one then-minister told me, suggesting that Mr Machar's fellow ethnic Nuers wanted power at the expense of Salva Kiir's Dinka community.

Ethnic tensions were only part of the picture: this was a political squabble first and foremost, and many of President Kiir's critics were from his own ethnic group.

That said, in South Sudan, politicians' political bases are often ethnic ones.

In July, President Kiir sacked all his cabinet - and Mr Machar.

The BBC's Alastair Leithead reports from Awerial, home to 75,000 people

Then came the events of 15 December, which will be debated for years.

President Kiir says he warded off a coup - his critics say he simply tried to crush them.

Outside the country, at least, President Kiir has not been able to convince that many people that this was, indeed, an attempted coup.

Move to war

Whatever the trigger, this quickly became a war, with Mr Machar leading rebel forces that have taken key towns like Bor and Bentiu, as well as oilfields.

A political squabble has become a conflict - and one with nasty ethnic undertones.

Both sides have been accused, by the UN and human rights groups, of ethnically motivated killings.

David is convinced he and many other Nuer were targeted in Juba, while Dinkas have said the same in areas attacked by the mainly Nuer rebels.

Already existing ethnic tensions have been exacerbated dramatically by this fighting.

However, prominent Nuers like the army chief James Hoth Mai and the Foreign Minister Barnaba Marial have not joined the largely Nuer rebels, while Mabior Garang - a Dinka, and the son of South Sudan hero John Garang - is part of Mr Machar's team at the peace talks in Addis Ababa.

The negotiations are a welcome positive step, but this crisis will not be resolved easily.

The first step will be getting a cessation of hostilities that holds.

The new country had suffered through decades of conflict with Khartoum

Then comes a more difficult task still: resolving the political fractures that triggered the conflict.

President Kiir has already told the BBC he will not contemplate power sharing, while Mr Machar wants the president to resign.

Ultimately it may be possible to come to some sort of political deal, informed by whichever way the military pendulum swings.

Yet even if that eventually happens, it would not resolve South Sudan's underlying problems.

The political class will need to govern for the people, and not for their own self-interest.

South Sudan must be weaned away from its reliance on destructive military solutions to political problems.

Above all, a comprehensive national reconciliation programme will be needed.

If all South Sudan's many ethnicities and interest groups do not manage to forge a genuine national identity, which puts the national interest first, the country's future looks bleak.

David, and millions of others, deserve better.

Fighting erupted in the South Sudan capital, Juba, in mid-December. It followed a political power struggle between President Salva Kiir and his ex-deputy Riek Machar. The squabble has taken on an ethnic dimension as politicians' political bases are often ethnic.

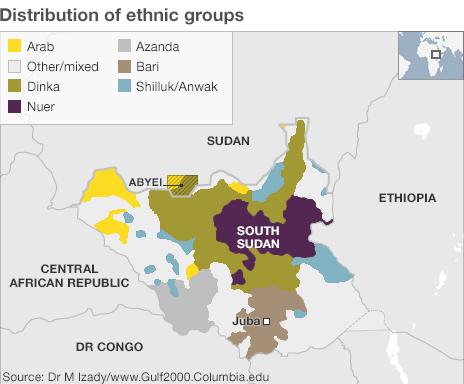

Sudan's arid north is mainly home to Arabic-speaking Muslims. But in South Sudan there is no dominant culture. The Dinkas and the Nuers are the largest of more than 200 ethnic groups, each with its own languages and traditional beliefs, alongside Christianity and Islam.

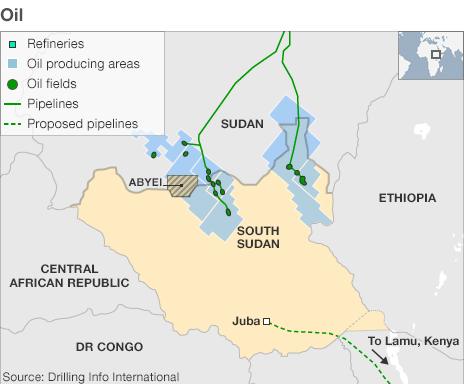

Both Sudan and the South are reliant on oil revenue, which accounts for 98% of South Sudan's budget. They have fiercely disagreed over how to divide the oil wealth of the former united state - at one time production was shutdown for more than a year. Some 75% of the oil lies in the South but all the pipelines run north

The two Sudans are very different geographically. The great divide is visible even from space, as this Nasa satellite image shows. The northern states are a blanket of desert, broken only by the fertile Nile corridor. South Sudan is covered by green swathes of grassland, swamps and tropical forest.

After gaining independence in 2011, South Sudan is the world's newest country - and one of its poorest. Figures from 2010 show some 69% of households now have access to clean water - up from 48% in 2006. However, just 2% of households have water on the premises.

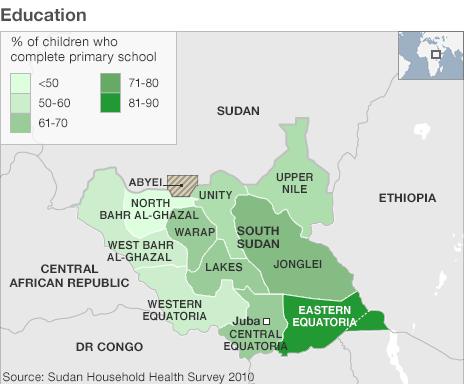

Just 29% of children attend primary school in South Sudan - however this is also an improvement on the 16% recorded in 2006. About 32% of primary-age boys attend, while just 25% of girls do. Overall, 64% of children who begin primary school reach the last grade.

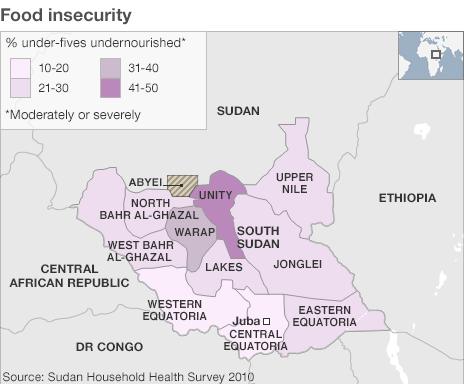

Almost 28% of children under the age of five in South Sudan are moderately or severely underweight - this compares with the 33% recorded in 2006. Unity state has the highest proportion of children suffering malnourishment (46%), while Central Equatoria has the lowest (17%).