South Sudan conflict: Inside ghost town of Bor

- Published

The BBC's Mark Lowen in a hospital in Bor said patients were shot in their beds by rebels

Turn out of the air strip, along the dusty road to Bor and you start to see it: mile upon mile of empty, burnt houses, every shack looted, the charred remains of vehicles and no sign of life.

This once-thriving place of 25,000 people has been reduced to a blackened shell, a ghost town.

Bor was the first major area to fall to rebel control when South Sudan's conflict erupted on 15 December.

It's been fiercely fought over ever since, changing hands a number of times.

But last Saturday, troops loyal to the government entered the strategically-important town and recaptured it.

It's been too perilous to visit until now.

But the BBC was among the first journalists allowed in, flown up on a government plane from the capital Juba, to see the aftermath of war - and the nightmares that remain.

Lt Gen Malual Ayom Dor, the commander in the town, sits under some trees, taking shelter from the midday sun.

"It was a fierce battle here," he says, "but an important victory. Now, though, I want the people to return and resume their normal lives."

Can Bor recover? I ask.

"Yes but it will take time for those traumatised to come back," he replies. "Some of them, including my mother, are in the bush. I have not had any contact with her. I don't know if she's alive."

Stench of death

It is over a month since fighting began here. The cause was a political row within the governing party - a power tussle between the President, Salva Kiir and his former deputy, Riek Machar, relieved of his duties last year.

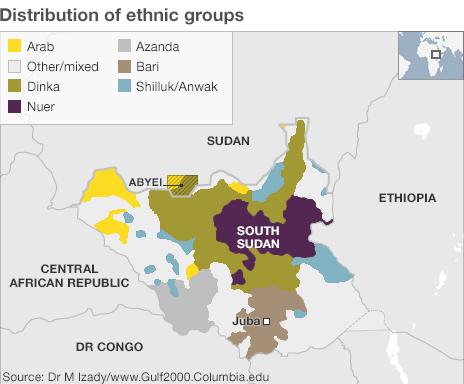

But it's taken on ethnic overtones: The Dinka people of the president pitted against the Nuers of his rival.

The market is now a heap of mangled corrugated iron and shattered glass

Reprisal killings have reduced towns like Bor to rubble. Both sides accuse each other of mass atrocities and the UN is now investigating possible war crimes.

The dead are many here - and not yet cleared. At the hospital, the scenes are truly horrific. Rebel soldiers ransacked it twice, killing people in their beds.

Outside, the remains of two patients lie rotting in the afternoon sun. One has an amputated leg, the other lies next to his crutches.

The ward has been looted: a few mattresses remain, but little else.

On one bed, under a pile of sheets, lies the body of a woman murdered as she was attempting to recover in hospital. The floor beneath is stained by a pool of blood. The stench of death and rotting material is overwhelming.

Cowering in the corner are three women who survived. One, deeply malnourished, lies in her bedclothes, unable to talk.

But Meria Jerchaoul does talk: Her vacant eyes and rasping voice tell of her suffering. She doesn't know her age - but says she's very old, perhaps over 50.

"The rebels came in to ask for money and a phone," she says. "I told them I had neither. They took my bags and there was some money that fell out. So they shot me through my shoulder." She shows where the bullet went in.

"Then they tried to rape me. But I said to them I'm too old to sleep with a man so if you want to kill me, kill me. I could never see the Nuer people again. If I were to hear them come back here, I would die."

In a makeshift mortuary, five more corpses lie rotting. It is just so raw here.

'My heart bleeds'

Down the road lies the once-bustling market. It is now utterly destroyed, a heap of mangled corrugated iron and shattered glass. Walking through the remains is the mayor, Nhial Majak Nhial.

"This was actually South Sudan's dream town," he says.

The BBC outlines the background to South Sudan's crisis - in 60 seconds.

"It was the cleanest, safest place in the country. Now it's brought down to ashes. The question is how can we rebuild people's confidence and how long it will take to come back to life."

I ask the mayor how he feels when he looks at what his town has become.

"My heart bleeds," he says, kicking away some of the rubble. "It is just terrible."

Bor has a dark history, now repeating itself. In 1991, 2,000 Dinkas were massacred by Nuers, led by Riek Machar. Many more died of starvation. It was a wound that was beginning to heal. But now a fresh conflict has torn apart this newly-formed country.

As we boarded the government plane out of Bor, we left behind the horrific scenes. But the mental images will be hard to erase.

The government is now edging towards victory here, recapturing all the major towns - though it's not inconceivable that the rebels will regroup.

But even if a ceasefire comes, reconciliation may not. And it's hard to see how these two communities, ripped apart by fighting and mistrust, can truly live together again in peace.

Fighting erupted in the South Sudan capital, Juba, in mid-December. It followed a political power struggle between President Salva Kiir and his ex-deputy Riek Machar. The squabble has taken on an ethnic dimension as politicians' political bases are often ethnic.

Sudan's arid north is mainly home to Arabic-speaking Muslims. But in South Sudan there is no dominant culture. The Dinkas and the Nuers are the largest of more than 200 ethnic groups, each with its own languages and traditional beliefs, alongside Christianity and Islam.

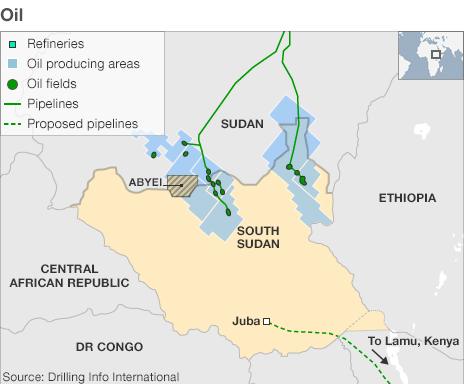

Both Sudan and the South are reliant on oil revenue, which accounts for 98% of South Sudan's budget. They have fiercely disagreed over how to divide the oil wealth of the former united state - at one time production was shutdown for more than a year. Some 75% of the oil lies in the South but all the pipelines run north

The two Sudans are very different geographically. The great divide is visible even from space, as this Nasa satellite image shows. The northern states are a blanket of desert, broken only by the fertile Nile corridor. South Sudan is covered by green swathes of grassland, swamps and tropical forest.

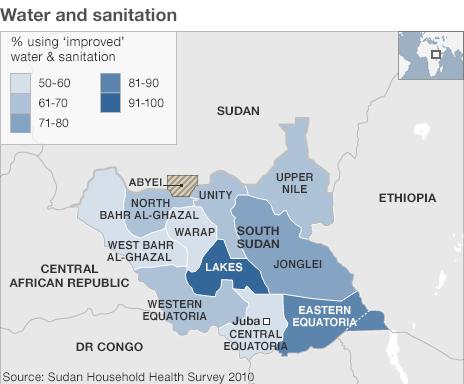

After gaining independence in 2011, South Sudan is the world's newest country - and one of its poorest. Figures from 2010 show some 69% of households now have access to clean water - up from 48% in 2006. However, just 2% of households have water on the premises.

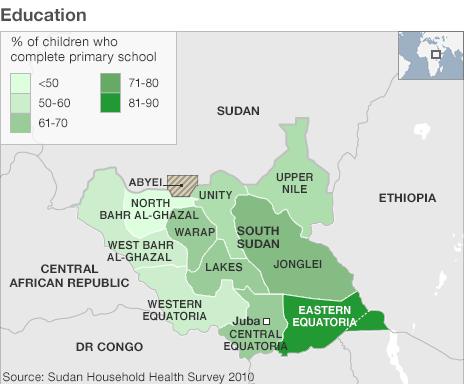

Just 29% of children attend primary school in South Sudan - however this is also an improvement on the 16% recorded in 2006. About 32% of primary-age boys attend, while just 25% of girls do. However, 64% of children who begin primary school reach the last grade - completion rates are shown on the map above.

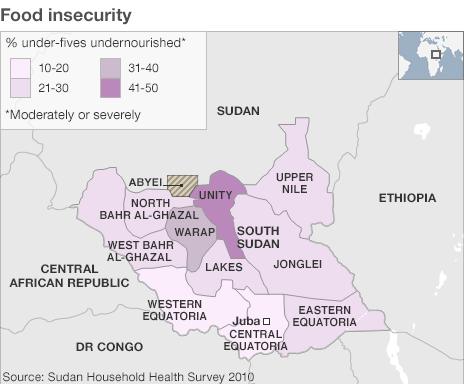

Almost 28% of children under the age of five in South Sudan are moderately or severely underweight - this compares with the 33% recorded in 2006. Unity state has the highest proportion of children suffering malnourishment (46%), while Central Equatoria has the lowest (17%).