Letter from Africa: The power of a name

- Published

- comments

In our series of letters from African journalists, Nigerian writer and novelist Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani considers the growing trend for name-changing.

Following their recent walloping by Nigeria's Super Eagles at the African Nations Championship, the South African national football team is once again considering changing its name from Bafana Bafana, which means "the lads".

They reckon that the name may have something to do with their fortunes, that it is time their team started playing like men.

A few years ago, troubled South African footballer, Jabu Mahlangu, also changed his surname from Pule, saying that the former name was jinxed, external.

Names are important in Africa.

In some societies, ceremonies are organised for the specific purpose of naming a new child.

During the naming ceremony for my sister's twins, printed sheets with the children's English and traditional names - and their different meanings - were handed out to the dozens of guests.

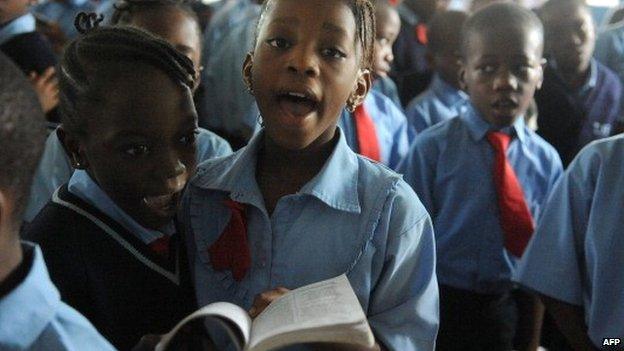

Parents in Nigeria place a great deal of importance on the names they give their children

Many African children are given at least three names. Each is carefully selected to reflect the circumstances of the child's birth, the family history, the parents' status or the expectations for the child's future.

The general belief is that a person's name can influence his behaviour and circumstances.

I have heard a number of people associate the paparazzi hunt that inadvertently led to Princess Diana's death, with her being named after Diana, the goddess of hunting.

In my church, on the second Sunday of each month parents wishing to dedicate their new babies to God line up on the pulpit with their children.

The mother or father then announces each child's names and the meanings. Sometimes, the congregation bursts into spontaneous cheering and applause when a particularly promising meaning is announced.

A young Nigerian man I know changed his surname from Ihimoyan to Moyan; "Ihi" was a deity that his family worshipped generations ago.

He no longer wanted to bear the name of a god he did not know, especially since his family is now Christian.

My friend, Iyabo, also changed her name to Busola; Iyabo means "mother has come back" and she no longer wanted to be seen as a carry-over of someone else.

These are just two out of the growing number of today's Nigerians, who, dissatisfied with their given names, are altering them to reflect a new outlook.

You are now likely to see a Mr Alex who used to be a Mr Agwu or Nkiruka who was Azuka.

Some of the names may sound very similar to the ones they have replaced, but their meanings are radically different.

Nkiruka, for example, means "what lies ahead is greater" while Azuka means "the past is greater". Agwu is the Igbo deity of divination, thought to be a malignant and ruthless force.

Cows vs tigers

Whole communities are also changing their names.

In 1992, the people of my ancestral village in the south-eastern state of Abia voted to change our name from Umuojameze, which means "children of Ojam, the king".

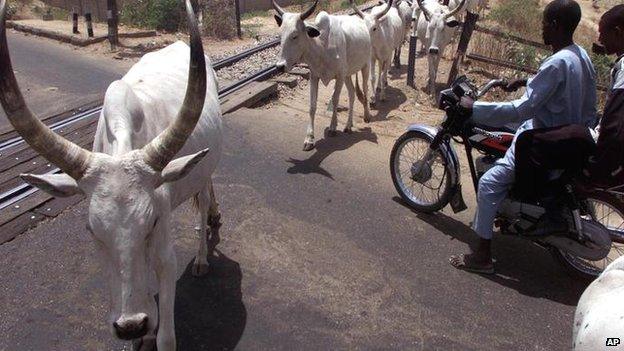

The villagers felt the name Ehi, meaning cow, failed to show their strength

Ojam was a deity the people used to worship. The villagers attributed the spate of sudden deaths in the community to Ojam's yearning for a long-overdue sacrifice, and wanted to make it clear that we no longer wanted anything to do with him.

Umujieze, the new name, sounds similar to the old one, but means "children who hold the kingship".

The late Reverend Father Stephen Uche Njoku, author of the book Challenge and Deal with Your Evil Foundations, believed there was a strong case for people and communities to change their names if they have disagreeable connotations.

"In doing this, you are making a choice to initiate a process of transformation for yourself, your family or your community," he said.

According to him, the Nkerehi people in Orumba improved their circumstances by changing their name.

The old name evoked a brutish past that included human sacrifices to their various deities and shrines; the Nkerehi now call themselves the Umuchukwu, or "children of God".

"The community now has a missionary hospital, an international secondary school and a civic centre," Rev Fr Njoku said.

The village of Ehi in Ikeduru has also changed its name to Amaudo, meaning "land of peace".

Ehi means "cow". This name, people believe, was the reason they were constantly being dominated by the Agu, a neighbouring community.

Agu means "tiger", and a tiger is always likely to exert its strength over a cow.

Will 'Goodluck' prevail?

One of the most spectacular reinforcements of the idea that names have power has been Nigeria's President Goodluck Jonathan, who enjoyed a series of "lucky" outcomes that thrust him into the highest position in the land.

Goodluck Jonathan came from behind into Nigeria's top job after President Umaru Yar'Adua died in office

The removal of those above him - through no act of his own - led to his dramatic rise from a deputy state governor to president.

However, the potency of his name is currently facing its greatest test, as a result of aggressive opposition to his perceived ambition to seek re-election in 2015.

It should be interesting to see whether Mr Jonathan's famed "good luck" will ultimately prevail.

It should also be interesting to see what alternative names the South Africans may consider for their lads.

Whatever they eventually select, you can be sure that the rest of Africa will be watching to see what - if any - difference it will make.

If you would like to comment on Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani's column, please do so below.