Genocide hunters: Fight for Rwandan justice

- Published

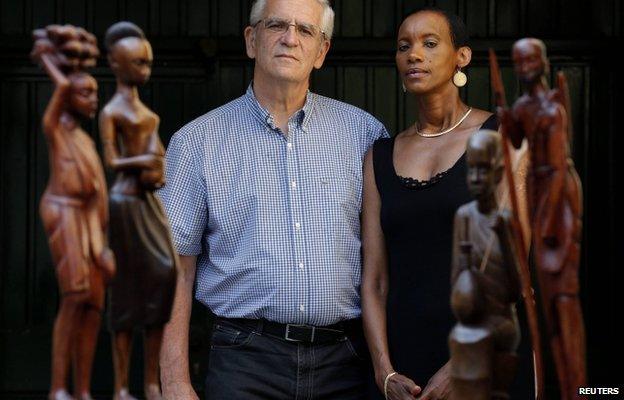

Alain and Dafroza Gauthier have spent the last 13 years hunting down people living in France suspected of participating in the Rwanda's 1994 genocide.

Mrs Gauthier's mother and dozens of other relatives were among some 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus who were killed in 100 days.

Living and working in the French city of Reims, the couple have dedicated all their spare time to putting together evidence.

They were inspired by the cases brought in Belgium against Rwandan fugitives and in 2001 set up an association - the Collective of Civil Plaintiffs for Rwanda.

Alain Gauthier told BBC Focus on Africa's Sara Mojtehedzadeh about their work:

My wife is Rwandan and many of her relatives were killed during the genocide. It's true that fact was a determining factor in our mission.

We are simply citizens with a conscience, as the presence of Rwandan genocide suspects in France is intolerable for the families of victims.

So without any [legal] knowledge we started this work and research.

Once we discovered a suspect in France, we were obliged to go to Rwanda to find witnesses - in order to make a case.

Those witnesses were either survivors or the killers themselves - those freed having served their terms and those who were still in prison gave us the best information.

Money has been a problem. In the beginning, we paid for our own travel, then the Collective of Civil Plaintiffs for Rwanda, which has about 150 members, helped us go. We have received some donations - but right now there is no real financial support.

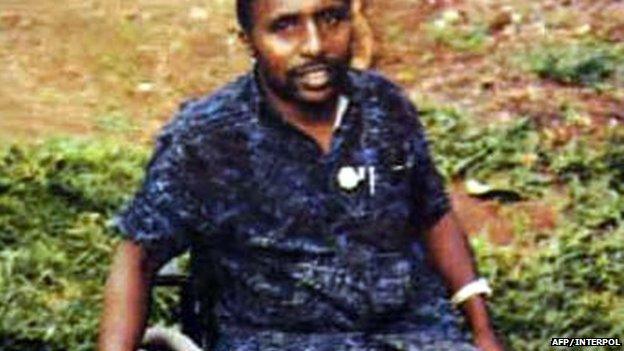

Pascal Simbikangwa is the first Rwandan genocide suspect to go on trial in France

To find suspects, we have followed up leads from those who have told us that they suspected people in their area or university may have taken part in the genocide - this information arrived from different sources. Then it was up to us to verify it and if we had the means we'd go to Rwanda to investigate.

It was a lot of work. For each case we have to go four or five times, staying often for two to four weeks.

I'd go to Rwanda in all my holidays - I was a teacher until I recently retired.

It required a lot of translation work, which my wife mostly did, and then we would give the information to our lawyers who would take several months to prepare documents to be accepted by the justice system.

'Without hate or vengeance'

Amongst the suspects we have discovered are three doctors, a priest, a former governor - most of them are respected members of society.

It's very difficult to know the true number of genocide suspects currently living in France - but so far we have filed complaints against about 25.

Without the work of our organisation, the Collective of Civil Plaintiffs for Rwanda, and others who have helped us there would be no investigation of genocide suspects in France.

There has been no help from the government. Then there's the work of the French justice system, which for a long time has dragged its feet and didn't have the means to pursue and investigate these people. That changed two years ago... but from the government there has been no help.

Trying genocide suspects is an occasion to remember the French government's role in Rwanda in 1994.

We think that there was on the part of that government, a diplomatic, financial and military complicity... so bringing that all up on French soil makes those formerly responsible uncomfortable - and some of them are still quite powerful.

Some 800,000 people were massacred in 100 days during the Rwandan genocide

So it doesn't bring pleasure to anyone, and it's clear that until now we've received no support at all from the French political world.

Pascal Simbikangwa is the first trial, which has come far too late. We just hope that it acts as a kind of incentive in French justice and that many others will soon be brought to trial.

What we do, we do because we believe it is only justice that can give the victims who are no more the dignity that was taken away from them.

We aim to do this "without hate or vengeance", to take the expression of the Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal.

What motivates us is essentially giving victims back their dignity.