Timbuktu waits for peace dividend

- Published

A year after French and African forces forced out Islamist militants from the historic city of Timbuktu, local residents are still waiting to reap the peace dividend, reports the BBC's Alex Duval Smith.

''We stayed throughout the 10-month occupation by the jihadists. We were not rich enough to leave,'' says fruit seller Aicha Dicko, 35.

''Now we see the people coming back thanks to travel grants, and receiving food aid once they get here, but there is nothing for us.''

Timbuktu has always had an eerie air about it - the sand and the stultifying heat combine to dull all noise.

Even at its busiest, the historic city bustles in silence; you only hear an approaching motorbike when it is very close, feet shuffle silently in the sand.

Now the silence is almost complete - the streets are empty, especially after dark.

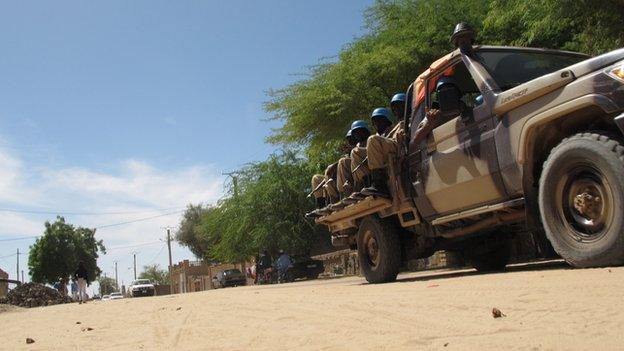

Even the market seems to be functioning in slow motion and the rare vehicles are the pick-ups of the Malian army or UN force.

For the region's rice growers the problem has been a lack of water, because of a shortage of diesel to run irrigation pumps, which has left them unable to thin their seedlings this season.

''Our harvest is bad,'' says Aboubakar Cisse, 45.

''If we want peace, the authorities must address the root causes of the war: People are hungry and thirsty. If the economy stays bad, men will go back to the armed groups, who pay you 300,000 CFA francs ($600; £400) to join up.''

Rumour mill of fear

Since 28 January 2013, when French soldiers put the Islamist militants to flight, an 800-strong UN force has been in charge of securing Timbuktu, alongside Malian soldiers.

But the city's traumatised residents complain that the troops do not patrol after dark, leaving Timbuktu in the grip of a rumour mill of fear.

The only vehicles seen in Timbuktu these days are military ones

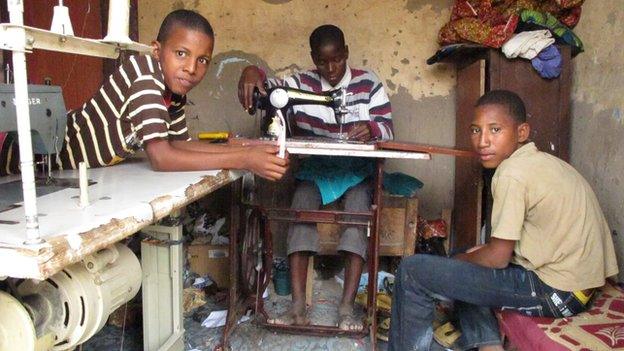

Trade is slow for most shopkeepers in Timbuktu

And militants still stage the occasional attack in and around the city.

Lack of diesel means streetlights only go on for a few hours each day.

Children do their homework beneath them but when night falls completely, worried parents call them indoors.

Displaced teachers, health staff and civil servants are offered government grants to return to Timbuktu but take-up is slow.

Public buildings that were looted and ransacked remain boarded up.

Only three banks have reopened.

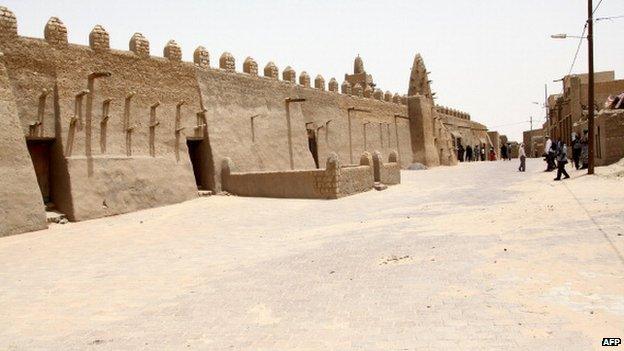

Commerce, which had been the lifeblood of the city since the 12th Century when it was founded on the thriving cross-Saharan trade in salt, gold, ivory and slaves, has ground to a halt.

'Nostalgia for occupation'

Bank manager Seydou Coulibaly says Tuareg and Arab livestock herders and businessmen are too afraid to return.

They fear lynchings because they are seen by black residents as having collaborated with the Islamists and Tuareg secessionists from the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA).

''Until last year, Timbuktu really depended on the easy availability of food and fuel from Algeria and Mauritania," says Mr Coulibaly, who has left his wife and children in the south of Mali.

"Pasta and juice from Algeria used to be what we bought from the Arabs. Those convoys were run by the same people who smuggled drugs and arms and abducted Westerners, and had links to al-Qaeda and others.''

Mr Coulibaly, whose branch was raided before serving as the Sharia prison while the Islamists were in charge, said the closure of the Algerian border and regular French counter-terror operations in the vast desert north of Timbuktu have largely halted the Sahara caravans.

Although life was tough for the Timbuktu residents who did not flee Islamist rule, with punishments such as floggings and amputations, and the destruction of some of the city's ancient mausoleums, some say they were better off in economic terms.

''The items we used to buy have become really rare. Everything has to come from Bamako now and the boat takes a week," Mr Coulibaly says.

"Prices have practically doubled or tripled. In Timbuktu there is actually quite a bit of nostalgia for the days during and before the occupation.''

Metalworker Issa Tandina recently completed an aid agency contract for school desks. But work is generally slow and he has laid off 15 of the 25 staff he employed two years ago.

''It was better when the occupation was on,'' he said. ''We did lots of repairs on their pick-ups and they paid. Now work is slower than ever.''

Roadside grill owner Souleymane Dicko is more optimistic; his economic barometer is the number of sheep he slaughters to feed his customers.

''It is getting better. Before the crisis it was five sheep, during the crisis it was one sheep and now we are back to two per day," he says.

"I have been grilling for 20 years and I am sure things will improve. We went to the brink. People have to be more patient.''

Tarred road lifeline?

For Timbuktu tourism director Sane Chirfi Alpha, even if the economic situation improves, the city will continue to struggle until the tourists come back.

''Tourism and its related activities - hotels, restaurants, crafts - accounted for 80% of the city's legal earnings and jobs," he said.

"But given the recent history of abductions, we cannot yet, hand on heart, ask international visitors to return.

Timbuktu is a World Heritage site and the great mosque of Djingareyber used to be a big pull for tourists

"The only way to rebuild the sector is to focus on national tourism and visitors from the sub-region.''

There are hopes that the construction of a 1,200km (745 miles) tarred road from Bamako to Timbuktu - begun in 2010 and abandoned in 2012 - will be an economic lifeline for the region.

''We have 580km to go. There is only one way forward and that is opening up these zones, getting them out of their isolation,'' said the head of the European Union delegation in Mali, Richard Zink.

But the EU-funded project has not restarted as planned in February as it is still not considered safe enough to put workers on road-building equipment on the ground.

Mr Zink also warns that trade alone cannot solve the problem.

''Development depends on commerce but also requires reconciliation,'' he says.

''There is a tendency in the of south of Mali to think: 'Send up the army.' But it won't work and the government knows it won't work.''