Rwanda genocide: 'Domino effect' in DR Congo

- Published

As Rwanda remembers the 20th anniversary of the genocide in which some 800,000 mainly ethnic Tutsis were killed, massacres of Hutus in neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo have been forgotten, writes the BBC's Maud Jullien.

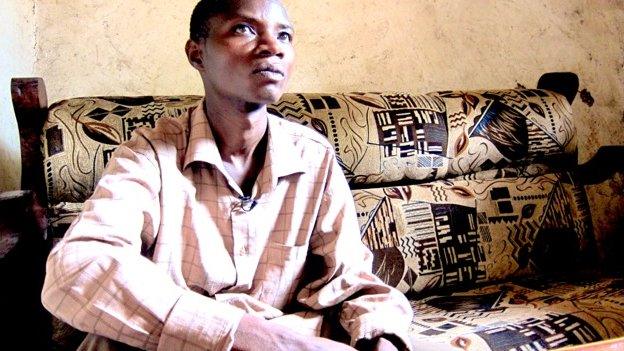

Jean-Marie is drunk again.

He has spent the day drinking with his friends in a bar in the eastern Congolese town of Rutshuru, where he has lived all his life.

"My head is messed up - all of us survivors, our heads are messed up," is the first thing he tells me in the town just across the border from Rwanda.

He was 17 when Congolese rebels entered Rutshuru in 1996 - and terrorised the town's large Hutu community.

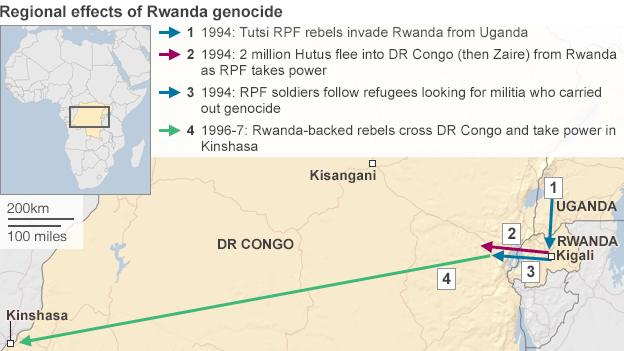

The AFDL rebels were supported by Rwandan army troops - made up of the former Tutsi rebels who came to power as the genocide ended in July 1994.

Almost two million Rwandan Hutu refugees had flooded to Rutshuru and surrounding areas in 1994, fearing reprisal attacks from the new Tutsi-led government.

"Thousands of Rwandan Hutu refugees arrived that year, after the genocide, looking for odd jobs here and there," Jean-Marie remembers.

"They were civilians and soldiers. We never saw any weapons but I know that they had brought some."

He says it was after the refugees' arrival that security started deteriorating and roadblocks were set up where people were asked for money.

'Liberators'

It was these armed refugees that the AFDL and the Rwandan troops said they wanted to track down.

When the gunfire began in Rutshuru, the talk was that the "liberators were coming" and all the refugees would go home, Jean-Marie says.

Initially Jean-Marie hid from the fighting with his father outside the town, but they eventually decided to venture back in search of food.

As they made their way towards the town, people warned them that they would be killed if they spoke Kinyarwanda - a language spoken on both sides of the border by both Hutus and Tutsis.

They were stopped by fighters before they could enter Rutshuru and asked to show their ID cards.

"When they saw our names, they took us," says Jean-Marie.

They were taken to a prison, and their identities were double-checked.

Because their surname, which Jean-Marie does not want to reveal, was Kinyarwandan, they were singled out and their arms tied behind their back.

"They took us away in groups of five to throw us into latrines or any other large holes in the ground," Jean-Marie says.

"They had instruments called 'foca-focas', a kind of small metal hoe, about 25cm [10in] long, with two hooks at the end," he said.

"They hit you first on the left of the head, then on the right, and if you resist, in the back of the brain.

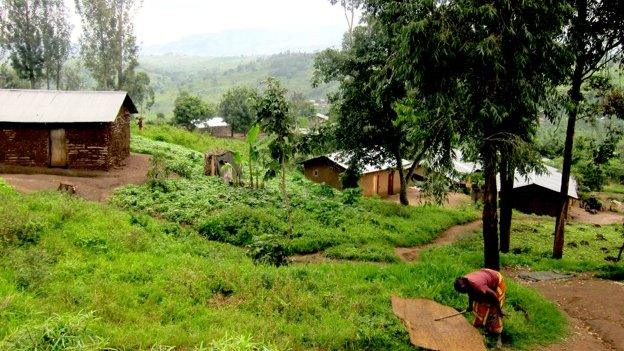

Rutshuru, a town in the lush hills of North Kivu province, has a large Hutu community

"Then you fall directly into the hole and you die, with your hands tied behind your back."

He said the women, who had been put in a separate group, were killed during the day, the men at night.

After seeing his father fall into a hole, Jean-Marie decided he had to try to escape.

"After my father died, I ran, but I fell to the ground just five minutes after. They started shooting at me from two sides, and God told me to pretend to sleep," he says.

"I had blood on my torso and stomach, so I rolled over a bit and God told me to stay still like that for 45 minutes.

"Then they left to execute the others who had stayed behind. God told me to get up, and I did so, painfully, and walked to a nearby town, Lumberisi, with my hands still tied behind my back."

No justice

His father's body, along with hundreds of others, were covered with earth and left to decompose.

The Rwandan-backed ADFL went on to march across the country - the size of western Europe - eventually ousting long-time leader Mobutu Sese Seko and installing Laurent Kabila as president.

It is now been 18 years since these massacres, and there has been no trial, no memorial, no official count of those killed.

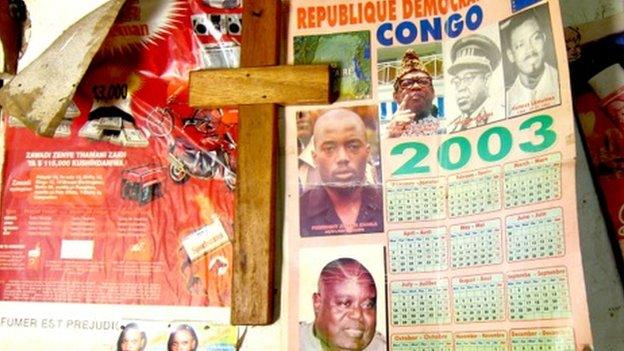

An old calendar on the walls of Jean-Marie's house shows all of his country's leaders since 1960

Jean-Marie says he does not believe in politics, but he keeps an old calendar on the wall of his one-bedroom house with five faces printed on it showing all the country's leaders since independence.

He likes to keep it as a reminder of a certain period in his life.

Families of the victims, many of them Hutus from DR Congo, want the events to be documented and the truth to be out in the open, but they are too afraid of reprisals to demand justice, Jean-Marie says.

He believes powerful politicians in Kinshasa have no interest in revisiting history.

President Joseph Kabila himself was among the rebels who put his late father in power.

In 2010, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights published a report documenting serious violations of international humanitarian law in DR Congo between 1993 and 2003.

It estimated tens of thousands of civilians, mainly Rwandan Hutu refugees and Congolese Hutus, were killed.

It accused Rwanda of war crimes and suggested certain crimes committed in the DR Congo between 1996 and 1998 could amount to genocide against the Hutu population - accusations flatly rejected by Rwanda's government.

The Congolese government says it has asked for help to set up a tribunal to look into these alleged crimes as it cannot do so on its own.

'Domino effect'

It is widely believed in eastern DR Congo that the Rwandan genocide was the start of the region's problems.

"People don't talk about it enough… but the Rwandan genocide was like flicking over the first domino," a human rights activist in the city of Goma told me.

The AFDL was the first of several Rwandan-backed groups to take up arms in DR Congo.

Uganda financed several others and dozens of local self-defence militias emerged in the late 1990s, initially as a reaction to the foreign or foreign-backed groups, to defend local communities - which were in turn armed by the Congolese government.

The mass graves in Rutshuru are overgrown and unmarked

Today there are more than 30 armed militias in eastern DR Congo still making a living from the region's minerals - trafficking, poaching, taxing and pillaging.

In Rutshuru, there are two mass graves dating back to the 1996 massacres - though it would have been impossible to guess what they were.

One is covered with overgrown plants and rubbish, encircled by barbed wire, behind the town's police station; the second is slightly larger, on a hill, with nothing more than barbed wire to indicate its existence.

"My heart holds many secrets," says Jean-Marie, his eyes glazed with alcohol.

"But my sons should know where their grandfather was killed. They should know why my hands were tied."

Still looking lost in his memories, he says: "It's true that God forgives, but this always stays in your heart."

The Africa Debate - How well has the Great Lakes region recovered from the genocide? - will be broadcast on the BBC World Service at 1900 GMT on Friday 11 April and will then be available to listen to online or as a download.