Oscar Pistorius 'close to disaster'

- Published

Chastened by two days of tough questions, Mr Pistorius arrives for a third day at the hands of Gerrie Nel

I'm tapping this out in Courtroom D, on a hard bench, at the end of an extraordinary, roller-coaster week of drama, tears and confrontation.

The Pistorius family are sitting on the row just in front of me, and it is hard not to follow events through their own, visceral reactions, as they flinch and cry.

A few yards to my right, I can see Reeva Steenkamp's mother, June, staring - almost trance-like, hour after hour - at the man who killed her daughter.

The memory of the athlete's remorseful tears earlier this week has been quickly supplanted, at least in my mind, by the fury of prosecutor Gerrie Nel's cross-examination - the initial shock of his showing the graphic photograph of the victim's head wound, and now the compelling second-by-second analysis of the night itself.

So who has the upper hand?

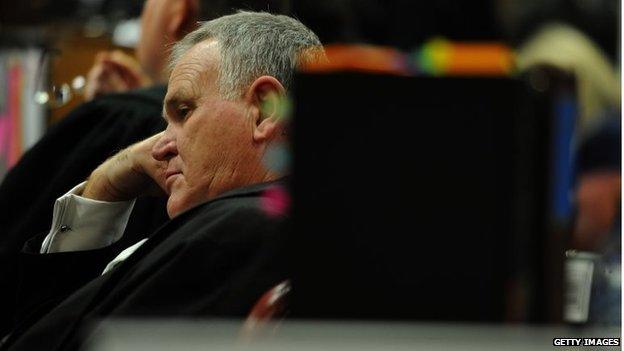

Gerri Nel has encouraged Oscar Pistorius to engage in legal arguments - in which the athlete has struggled

The Pistorius family, in court, have also felt the blows landed by the State against their relative

This week has reminded me, once again, of the dangers of taking anything for granted in this trial. And there is still a long way to go.

And yet I would conclude that, overall, these past few days have been close to a disaster for Mr Pistorius - and one that largely seems to have been of his own making.

Let's leave aside, for a moment, the four bullets fired through the toilet door, and examine the three other gun-related charges the athlete decided to fight at the same trial. It is a decision that must surely be haunting him and his team right now.

'Cocky schoolboy'

One was a very minor issue about keeping some of his father's ammunition in the house.

On the stand, Mr Pistorius' attempt to go head-to-head in a pedantic legal argument with prosecutor Gerrie Nel was like watching a cocky schoolboy trying to score points off a university professor. He failed.

Another was the gunshot under the restaurant table in Johannesburg. This was even worse.

Instead of admitting he had fired it by mistake, Mr Pistorius tried to suggest that the gun's trigger had somehow been pulled independently - that he had not been directly responsible for the action.

Mr Nel scoffed at the "miracle" shot, and at the athlete's reluctance to accept blame.

It seemed clear to many that Mr Pistorius made a mistake. But his casuistry impressed no-one, and nor did his desire to keep the "story" out of the media, when surely he should have been more concerned about answering to the police about an extremely dangerous act.

Then came the sunroof gunshot - preceded by a weekend boating party to which the athlete admitted he had taken his loaded pistol.

His then girlfriend Samantha Taylor, and former friend Darren Fresco, earlier both told the court, under oath, that Mr Pistorius had fired his gun out of a moving car after an altercation with a police officer who, well within his rights, had spotted Mr Pistorius' pistol on the passenger seat and picked it up.

Mr Pistorius' criticism of the policeman's lack of "courtesy" and "professionalism" spoke volumes about his attitude to authority in South Africa - a country where some cocky white men still do not always show appropriate deference to the country's racial sensitivities and legacies of apartheid.

But it was the athlete's lawyerly insistence that his two friends had "fabricated" evidence against him that struck me as most damaging.

If you check the record, you will see that Mr Pistorius never actually denied firing a shot. But I've been led to understand - and he hinted as much in court - that he maintains he did so on a different day, in different circumstances. So why not admit that to the police, take the rap, and move on?

In contrast to the often emotional Pistorius family, June Steenkamp has had a steely focus throughout

Away from the help of his defence lawyer Barry Roux, Mr Pistorius has appeared vulnerable

Instead, by now already badly bruised, Mr Pistorius staggers on to the central question of this trial. And I am not talking about the position of the various fans and plugs and curtains and duvets in his bedroom that so preoccupied Gerrie Nel on Thursday. The police clearly moved some evidence, so I doubt the prosecution is going to find any certainties there.

The real question, of course, is why did he shoot four times through that toilet door?

On Wednesday, Mr Pistorius said he had done so "accidentally." The word is crucial, but watching him trying to explain it under rigorous cross-examination has been uncomfortable, to put it mildly.

Mr Pistorius must know that if he admits he shot at the door "deliberately" - regardless of whether he thought Reeva Steenkamp or half a dozen armed burglars were inside - then he has also come perilously close to admitting he intended to kill someone. That makes it easy for the prosecution to argue they have proved it was murder, or at the very least culpable homicide.

And so, the athlete continues to walk his narrow tightrope and insist on four "accidental" gunshots - on top of the other accident in the restaurant. Mr Nel, meanwhile, is gleefully tugging on that same rope.

Ultimately, Mr Pistorius's strategy at this trial is to argue that he is, in an admittedly repentant and awkward fashion, innocent on all charges.

Perhaps so. But it is an intellectually nuanced and demanding argument that the athlete, by turns distraught and pedantic, often struggles to articulate, alone on the stand with no counsel to fall back on.

We still have, as I mentioned earlier, a long way to go in this trial. I suspect the defence will produce more expert witnesses to undermine and muddle more of the state's "premeditated" case - the female screams, and the bangs heard by some neighbours.

But this trial is a curious one - not a whodunnit, but a whydunnit - and Mr Pistorius still has a minefield ahead of him, and a daunting adversary encouraging him to stumble.