South Africa’s townships - a magnet for entrepreneurs

- Published

Despite their poor clientele, South Africa's spaza shop owners are able to make a living

South Africa has been a magnet for immigration in recent years, with many of those coming to Africa's second-largest economy to set up small family businesses in bustling townships.

But their business acumen has not always been welcomed at first by local people, as Kharul Islam, a slightly built Bangladeshi in his mid-20s, can affirm.

He runs a small grocery shop, known in South Africa as a spaza, in the crime-ridden area of Delft, about 30km (19 miles) east of Cape Town.

With its red painted exterior, the Comic Grocer is easy to spot from a distance; look closer and you notice the bullet-proof glass and the metal mesh guards

"I've had to put in bullet-proof glass to protect me. When I first came people threatened to kill me," he says.

It was local criminals who tried to intimidate him when he moved in three years ago.

Last year alone, the area recorded 113 murders, 129 cases of attempted murder and nearly 1,500 cases of violent crime in 2013, according to police statistics.

"But now that they know me it's better and safer," he says.

His customers come in to buy single items like a roll of toilet paper, sugar, milk or bread, but it is clear that the Bangladeshi, who has a Tanzanian and Zimbabwean to assist him, has developed a good relationship with them.

Trading skills

Operating in an economically depressed area like Delft, with a 43% rate of unemployment, the foreign shop owners have adapted their products to meet the needs of their customers.

Like many foreign traders, Mr Islam sells small quantities of essentials like tea, coffee, sugar and flour.

Like at other spaza shops, many of Altaafur Rhaman's customers buy just a single item

"People don't have money to buy the pre-packed quantities provided by the suppliers so I make it easier and more affordable for them. I give them what they need."

Following the advent of democracy in South Africa in 1994, it was initially Somalis, fleeing their country's civil strife, who made inroads into the townships.

Using their renowned trading skills, they established themselves in the spaza market, often to the displeasure of local traders who saw their share of this business sector cut back.

The past five years has seen a new wave of traders from mainly Bangladesh - and to a lesser extent countries like Pakistan, Egypt and Ethiopia - trying to squeeze into what has become an increasingly competitive market.

The Spaza News industry newsletter says South Africa's spaza sector comprises more than 100,000 enterprises with a collective annual turnover of 7bn rand (about $663m; £395m).

Eight urban sites studied between 2010 and 2013 showed that nearly 50% of spaza shops were operated by foreign entrepreneurs, according to researchers at the University of Western Cape's Political Science Department and the non-profit organisation Sustainable Livelihoods Foundation.

'Opportunities for locals'

Most of the foreigners work a punishing 16-hour day, seven days a week, and most have a mattress and washing facilities in a modestly furnished room attached to the shop.

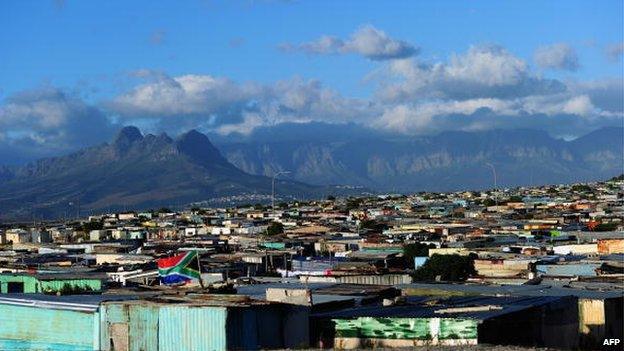

Protests about the lack of basic amenities in townships are fairly common in South Africa

Not surprisingly, local shop owners have complained about the influx of foreign competitors who they say have impacted on their trade.

Evelyn Domingo, who runs her spaza shop not far from Mr Islam's, says her business has suffered over the past two years.

"I'm not happy; business has been slow since the foreigners started opening up. They are able to keep their prices down because they group together which enables them to buy at lower prices," she says.

"It's only the lotto [national lottery] tickets that attract people to my shop because it's only me and the post office down the road that sells the tickets."

Ms Domingo, whose husband was killed in a robbery two years ago, says the government promised to do something to help local traders, but has failed to do so.

While many of the foreigners, especially the closely knit Somali community, have managed to secure cheaper prices from wholesalers by buying in bulk, the influx of migrant traders has also provided business opportunities for local entrepreneurs like Mujeeb Rockman.

He has been supplying items like washing powder, toilet paper, sweets and cool drinks for the past year to small shops in the townships.

"The majority of locals are selling their shops off to foreigners or renting the buildings out to them," he says.

"The number of foreign-run shops has increased dramatically which is not a bad thing because they are good business people; they like to bargain for a better price.

"What also helps is that they don't have extravagant lifestyles, so they are able to cope with smaller profit margins because they are able to live with less."

Learning local languages

The success of the foreign business people in the townships has made them an easy target for local criminals, allegedly backed in some cases, orchestrated campaigns by envious local spaza owners.

Whenever there is a protest about the lack of basic amenities - a fairly frequent occurrence in townships - the foreign-owned businesses are often among the first to be targeted by opportunists within the community who loot their shops.

There is a high level of unemployment in most townships in South Africa

Security tends to be tight at spaza shops

But things are changing, as three men convicted of killing and robbing a Somali trader and injuring two of his compatriots last year received jail sentences of 25 and 30 years.

"We have tried to change the perception that we are easy targets. We are also working closely with the police," says Mohamed Aden, spokesperson for the Somali Association of South Africa.

Altaafur Rhaman, Mr Islam's brother-in-law, also runs a spaza in Delft, although it is a much smaller concern.

Well-protected behind a strongly barricaded mesh steel safety gate, which features a small opening through which sales are conducted, Mr Rhaman is aware of the dangers of trading in an area like Delft.

"It's dangerous here, many of my friends have been robbed and there are many poor people here, but it's OK, I'm able to make a living," he says.

"I try to be friendly and to help where I can."

Mr Rhaman has tried to win over the residents in his immediate vicinity.

He says he is trying to learn the local languages - Afrikaans and Xhosa - and also tries to understand the needs of the economically depressed community.

"I like to buy from him, he's very nice," says a young woman who has come to buy eggs.

Another customer, a neat young man in jeans and a fashionable baseball cap, agrees: "I like them [the Bangladeshis], not everything is cheaper than at the locally owned shops but it's a pleasure to buy from them."