Zimbabwe's opposition - a Greek tragedy

- Published

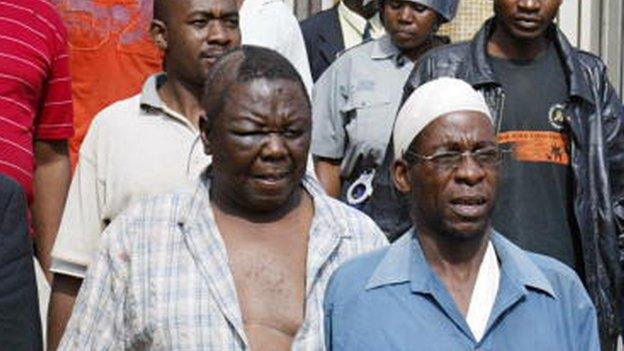

"Warrior" Tsvangirai (r) tried to oust "King" Mugabe (l) but was himself outflanked

It is a story with some of the qualities of a Greek tragedy.

A brave warrior rallies his countrymen to try to oust an unjust king.

For years they struggle, enduring great hardship and showing true courage.

Then one day the king - also weakened by the fight - offers a truce, and invites his enemy to join him in his palace.

Warily, the warrior joins forces with his nemesis.

As the years go by the warrior begins to enjoy palace life.

When he finally makes another move to oust the king, he discovers that many of his own supporters have abandoned him. He is cast out of the palace.

Soon afterwards, the warrior's closest aides - those who had always warned him against the alliance - draw their knives and stab him.

Welcome - with a little artistic license and apologies to Sophocles - to the troubled world of Zimbabwe's opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), and its veteran leader, Morgan Tsvangirai, who was turfed out of his position last week amid allegations of corruption, abuse of office, and weak leadership.

"Mr Tsvangirai has been suspended," one of those wielding the knife, Elton Mangoma, told me by phone.

"I think he'll come to his senses and realise it's futile to carry on. He has nowhere else to go," said Mr Mangoma, who implied that Mr Tsvangirai's taste for "big man politics" and his reluctance to step down, had turned him into a copy of the man he's fought so long against - President Mugabe.

But Mr Tsvangirai is not going quietly.

In language that would appear to rule out all future compromise , he has now accused his old allies - including the formidable Tendai Biti, who was also beaten and charged with treason by Mr Mugabe's forces - of working with Zanu-PF to "betray the people".

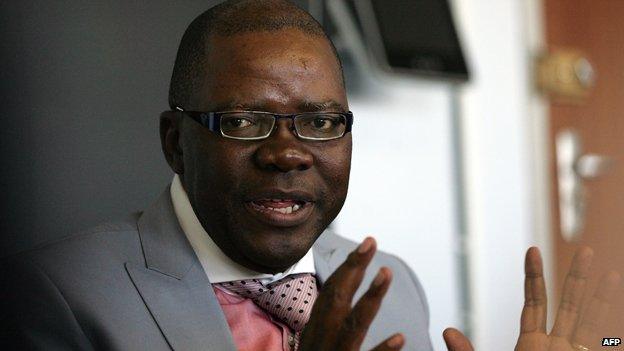

Morgan Tsvangirai accused Tendai Biti of being used by state security agents

Mr Tsvangirai described Mr Biti as a treacherous hypocrite and an opportunist who "believes in nothing" and would now be dismissed from the party with eight other rebels.

How did things get this nasty?

Few would question Mr Tsvangirai's courage as an opposition leader in the bruising years before his controversial alliance with Mr Mugabe.

But the 2008 deal that saw the MDC brought into a power-sharing government, following an election campaign violently disrupted by Zanu-PF, was always going to be a risky move.

'Tyranny'

Mr Tsvangirai tried to sell it as a Mandela-esque gesture towards national reconciliation.

It was a much grubbier affair than that.

Amid the squabbling, life is getting tougher for many Zimbabweans

The deal did help revive Zimbabwe's crumbling economy - thanks to Mr Biti's role as finance minister - and put an end to the bloodshed, but Mr Tsvangirai himself soon became a largely symbolic figure, mocked for his colourful private life, his expensive house, and his golfing; and consistently outmanoeuvred by Mr Mugabe.

Then came last year's election.

While the MDC and most western nations believed Mr Mugabe rigged the results to win once again, it was also clear that the opposition had lost headway.

"There's no point in pretending you are strong when you are very weak," said Mr Mangoma, arguing that the party needed fresh blood and fresh ideas in order to prepare itself "to remove the Zanu-PF dictatorship" at the next election in 2018.

This is not the first time that the MDC has split.

Morgan Tsvangirai (l) has been arrested and beaten in his time as MDC leader

MP David Coltart joined a 2005 breakaway group, and still bemoans "the deeply rooted… culture… whereby a party starts to reflect the traits of the tyranny it opposes".

Mr Coltart, now a member of the MDC-M faction, blames a lot of the problems on the "enormous pressures brought to bear on leaders" during the fight against Mr Mugabe.

"The sheer nervous stress caused by a struggle like that causes people to fall apart, never mind political parties."

There is little doubt that the new split will only benefit President Mugabe, now aged 90, and his Zanu-PF, who are involved in their own succession battles.

Mr Coltart says he has "no doubt" that the MDC's troubles have been fuelled, once again, by state security operatives.

But his chief concern is that Zimbabwe's two main parties are now preoccupied with internal wrangling at a time when the country faces huge new pressures - with business confidence eroded, factories closing, tax revenues down, and a deflationary spiral choking the economy.

"I was hoping Morgan Tsvangirai would play the role of a political 'grandfather' and use his influence to facilitate the emergence of a more inclusive alliance of democratic forces," said Mr Coltart.

That seems unlikely now.