Why white South Africans are coming home

- Published

Many have felt the tug of South Africa and returned home

Hundreds of thousands of whites left South Africa following the ANC's landslide election victory in 1994. Twenty years on, the exodus shows signs of slowing, even reversing. Jane Flanagan spoke to some of those who have returned.

Nicky and Craig Irving spent five years in Australia before moving back to Cape Town with their three daughters.

They were among the last members of their respective families to emigrate amid fears over the crime wave that swept South Africa during the 1990s.

"The challenge to us from our relatives who had left was 'How can you raise your children in a country that is so violent and has no future'," Mrs Irving recalls.

"Our girls were 10, seven and nearly one at the time. We felt vulnerable living in South Africa, so leaving seemed the obvious thing to do."

Exodus

The Irvings were among 44,500 white South Africans who left the country in 2004, more than double the annual figure in 1996.

But after five years in Sydney and on a farm five hours drive from the city, the Irvings had had "enough of living in a sorted society".

They decided to return home and help tackle some of the challenges that had prompted them to leave South Africa in the first place.

"We could have decided to stay in Australia which, as people kept telling us, was a safe place for our children, but we decided to come back and try and make South Africa a safer place for all its children."

Mrs Irving, an architect, is now working with Cape Town officials to help improve Khayelitsha, the country's biggest township.

Someone who also left in the first wave, Angel Jones, was prompted to return on hearing Nelson Mandela reach out to a mainly white South African crowd on a visit to London in 1996.

"He told us: 'I love you so much. I want to put you in my pocket and take you home'," she recalls.

"We all stood there with tears running down our cheeks. I had grown up with so much shame about the colour of my skin, but Nelson Mandela really did change that for a lot of white South Africans. I knew then that I had to go home. It was the most amazing moment."

She came home in 1996, just as many of her friends were packing their bags to leave, and set up Homecoming Revolution which connects the homesick South African diaspora with potential employers back home.

'Pale male'

The exodus has steadily slowed however and there is evidence that many of those that left - whether for careers, over safety fears or political instability - are returning. Homecoming Revolution estimates that some 340,000 have come home in the last decade.

The idea that the "pale male" is not welcome in the South Africa, in the wake of a widespread implementation of affirmative action, is misplaced, Ms Jones says.

There is "no shortage" of opportunities for returning skilled professionals with international experience, particularly in finance and IT, she says.

But settling back into life in South Africa often takes time and some cannot put aside their original motivations for going. Around one in six returnees end up leaving again.

After 12 years in London, Greg Anderson, now 45, could not contemplate the idea of returning to South Africa.

However, the birth of his twin sons changed that, he says. He and his South African wife came home in 2008, and now have a third child.

"It wasn't just that the cost of childcare or the complicated logistics of having kids in a city," Mr Anderson says.

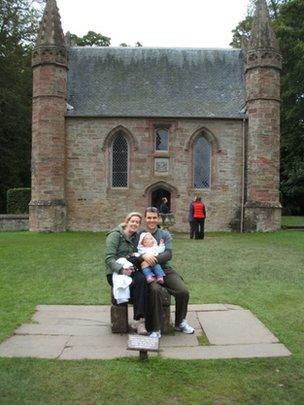

The Sinclaire family in Scotland before deciding to come back to South Africa.

"It was more that we wanted them to have the kind of childhood that we had enjoyed - running barefoot, being outdoors."

"To begin with, it was great to catch up with family and friends and enjoy the weather, but it took me a while to adjust to being back and I still miss London terribly," he says.

"Some of my South African friends thought we were mad. We all had British passports which is a real luxury these days. I suppose I do stick my head in the sand a bit over what is going to happen in the future, but for now I do think we are giving the children the best start in life they could have."

Feeling 'alive'

Lifestyle is one of the top three reasons given by white South Africans for deciding to go home, along with family connections and "a sense of belonging", according to Homecoming Revolution research.

For the 85% who do successfully reintegrate, there are certain aspects of life back home that perhaps only those who have left and returned can appreciate.

Ms Jones describes it as a "genuine feeling of being alive" that South Africans do not experience in new lives overseas, whether it is Britain, Australia or New Zealand.

"It's a trade-off to come back to South Africa and it is natural that people have very mixed feelings about it. In the end, the decision to come home is an emotional one.

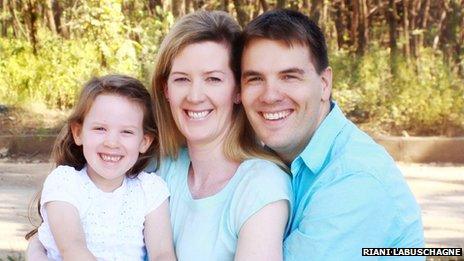

The Sinclaire family. Settling in on their return to South Africa.

"In South Africa, every small gesture has a ripple effect and that sense of connection is what people want in their lives. They can build lives outside of South Africa but that element will always be missing."

Kerry Sinclaire agrees. Just seven months after returning to Johannesburg, she appreciates how easy it is to make a positive impact.

"There are so many opportunities to be involved in other people's lives in South Africa in a way that you don't find anywhere else," she enthuses.

"In countries where the government takes care of so many issues, it becomes hard for an individual to make a difference. If you want to volunteer, mentor or empower someone in South Africa, there's really nothing to stop you."

Part of the solution

However, returning to a country where poverty, corruption and crime are rife has not been without its challenges for Mrs Sinclaire after six comfortable years in London.

"It has been hard at times," Mrs Sinclaire, 39, admits. "It's not easy to open a newspaper or hear about what's going on in South Africa, we have been sheltered from it.

"But we are finding our footing again."

The Sinclaires were one of four young South African families in their south London circle of friends who all returned within a few months of each other.

"It feels a very exciting place to be coming back to and also an exciting time for the country. We want to be part of the change that's happening in South Africa - part of the solution, not the problem," she says.

About the author: Jane Flanagan is a British journalist who has spent 10 years living in South Africa, between Johannesburg and Cape Town