Nigeria schools walk line between Islamic and Western traditions

- Published

Will Ross reports from a religious school in Kano

For Muslim children in northern Nigeria, memorising and reciting the holy Koran is an integral part of growing up.

Down an alleyway in central Kano, I find one of the many Koranic schools which have changed little in generations.

About 800 boys are sitting on mats chanting verses of the Koran, which they have written out on wooden tablets with short sharpened sticks, dipped in ink.

They do this for hours each day. For most of these boys, this is the only education they get.

Many come from villages far away. They board at the school where conditions are basic, to put it mildly.

Across northern Nigeria, it is estimated that about 11 million children get no access to mainstream education.

But there is a growing belief that reforms are long overdue and a broader education is essential.

"When I was growing up I didn't get any Western education. I only attended a Koranic schools like this one," says Abdurrahman Muhd, the mallam, or religious teacher, as he shows the students how to write the Arabic script.

"But we have to change to compete with the challenges of modern society."

Fatima says she wants to be a doctor or a lawyer when she grows up

When they return from afternoon prayers, about 30 of his students are given lessons in maths, Hausa, English and social sciences.

"Some of my own children have finished secondary school and are going to the next level after studying the Koran alongside Western education," says Abdurrahman Muhd, mentioning the word "boko" in the local Hausa language.

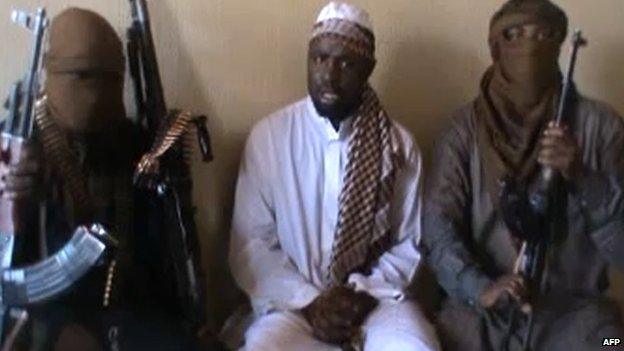

Boko Haram, meaning "Western education is forbidden", is the nickname of the extremist group which has killed thousands of people in recent years during a brutal campaign of violence.

'Good for the community'

It has attacked many schools in north-east Nigeria - including the boarding school in Chibok, from where hundreds of girls were abducted, and in Buni Yadi, where dozens of boys were killed in their dormitory.

Founded in 2002

Initially focused on opposing Western education - Boko Haram means "Western education is forbidden" in the Hausa language

Launched military operations in 2009 to create Islamic state

Thousands killed, mostly in north-eastern Nigeria - also attacked police and UN headquarters in capital, Abuja

Some three million people affected

Declared terrorist group by US in 2013

The group wants a strictly Islamic education and for boys only.

Boko Haram used to be extremely active here in Kano. Security has improved in what is the largest city in the north, although a suicide bombing on 18 May was an ominous warning that the threat persists.

The relative peace offers a chance to make improvements to the quality of education.

"Those children who don't go to school only stay at home and then they go out to sell things on the streets," Fatima, 12, tells me as we chat outside her community-based Islamiyya school in a suburb of Kano.

"If they are asked to write something short and simple, they can't. But I can read and write now," she says, beaming proudly.

"I stay with my grandfather but when I go home every weekend, I teach my younger siblings how to read and write and my mother is happy about that," Fatima says, before heading back to her English class.

The schoolgirls abducted from Chibok later appeared in a hostage video

It is a short walk to the home of her grandfather, Al Haji Sani Jibril. He is convinced that Fatima's education is good news for the whole community.

"I believe sending Fatima to school is like educating our whole society, because my granddaughter will influence her peers to go to school," he says.

"During my time, we did not have this opportunity to learn. I wouldn't want my children to suffer from the experiences I had," he says, adding that educated people are the only ones who have a say in today's society.

Path to peace?

British taxpayers are helping fund improvements to Nigeria's long-neglected education system, including these reforms to the religious schools.

Oil-rich Nigeria is not short of cash, but by offering technical expertise the goal is to improve the quality of education for both boys and girls.

There is a fear that more uneducated youth could end up as recruits for groups like Boko Haram.

Secular education is a relatively recent arrival in northern Nigeria

The Kano state governor, Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso, has thrown his support and financial clout behind educational reforms, including the modernisation of Koranic schools.

"I believe it is important to engage them to make sure that they are employable, so we can reduce the challenges we are facing today," says Mr Kwankwaso.

His government has now introduced a law banning parents from sending their children away for religious education without offering them financial support.

"We are all aware that there is certainly a correlation between illiteracy, poverty and conflict," he says.

Yardada Maikano, an educationist, says the demand for a modern curriculum has exceeded expectations

I asked if he was worried about the reforms, given Boko Haram's view on Western education.

"What we are doing here in Kano is to say that Western education is very relevant, Islamic education is very relevant and of course they have to go side by side," he says.

"That is the only way we can really make progress in this part of the country."

Colonial link

Controversy over education is not new here. Islam came to northern Nigeria more than 1,000 years ago. But secular education is a relatively recent arrival.

British forces, using mainly African troops, captured Kano in 1903. Since then, there has been a degree of resistance to "Western education" because of the link to colonialism and a perception that Islam was under threat.

So for those keen to see the old and the new integrated in the religious schools, there was initially some nervousness.

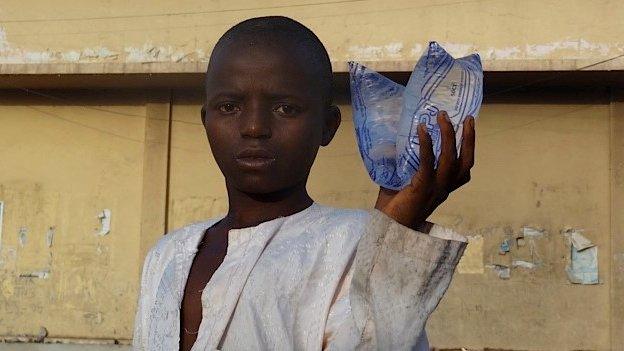

Better schooling could offer an escape from poverty for the young - such as this boy selling water in Kano.

"From the beginning, some people thought the programme was going to be small in terms of numbers," says educationist Yardada Maikano.

"But the demand has been huge as more and more mallams are calling for basic education to be integrated in their schools. So this demand is now a challenge.

"I feel overwhelmed, I feel elevated and I feel happy," she adds.

"And that is why I continue with the struggle to make sure that those that have not been enrolled are given a chance to have religious and secular education at the same time."

Improving education in northern Nigeria was already an immense task, even before Boko Haram started its campaign of violence.

But every day, people are working hard here to give all children a fighting chance of fulfilling their dreams.

Fatima already has high hopes. "I want to be a doctor or a lawyer - that is my goal," she says. "I will not get married until I achieve this goal."