South Sudan: Women raped under the noses of UN forces

- Published

Watch Karen Allen's Newsnight film in full

Emily was bitten, beaten and raped just a few hundred metres from the UN camp in South Sudan's capital, Juba.

Tomping camp is Emily's home - a vast, squalid sanctuary where thousands of South Sudanese now live cheek by jowl after a political fallout triggered a major military rebellion.

It has split the army in two and seen civilians targeted along ethnic lines.

Emily, a pseudonym for this 38-year-old mother of two, is testimony to that.

She is one of the few women in this fragile country who, despite the stigma of rape, has found the courage to speak out, in an interview for BBC Newsnight.

At a location away from the camp, she shows me her wounds.

Ambushed

Bite marks on her chest and back, and deep, crooked scars from where she was beaten with a stick.

Emily tells me she was gang-raped by what she says were pro-government forces largely drawn from the Dinka community - and it happened right under the noses of UN peacekeepers.

She was among a group of women returning from a trip to town when they were ambushed by armed men in what seems to have had all the hallmarks of a highly organised, ethnically charged attack.

It was executed not far from an SPLA (government army) position, right on the periphery of the heavily guarded UN camp.

Control of Bentiu has changed hands four times in recent months

"They stopped us at the first tree and ordered us to put down our bags.

"Then they took us to a second tree where they searched us, groped us and stole money and mobile phones.

"Then they led us to the third tree, where they raped us," Emily explains calmly.

Seven women were reportedly raped at the same spot that day.

Repeatedly raped

In a separate incident, another woman said she was abducted within sight of the camp.

She described how she was held in a disused shipping container and repeatedly raped by armed men in military fatigues.

The allegations are extremely hard to verify in the world's newest state, and claims of rape have been levelled at both government soldiers and rebel forces.

They point to an alarming trend - sexual violence on a scale investigators believe has not been seen in South Sudan before.

Reporting rates are low for sexual crimes committed during conflict and the means to gather the information are extremely limited in South Sudan.

Yet hundreds of cases are being reported of women being sexually abused, gang-raped, detained and their young sons castrated - singled out on ethnic lines.

Life in South Sudan

South Sudan is the world's newest nation and is bordered by six countries.

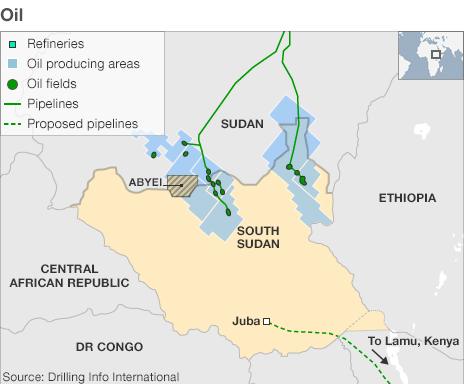

It is rich in oil, but following decades of civil war it is also one of the least developed regions on earth - only 15% of its citizens own a mobile phone and there are very few tarmac roads in an area bigger than Spain and Portugal combined.

Women and children have been displaced by the conflict

This makes the Nile River, which flows through regional centres, an important transport and trade route. Cattle are also central to life in South Sudan - a person's wealth is measured by the size of their herd.

Since South Sudan overwhelmingly voted to break away from Sudan in 2011, the government's main concern has been to get oil flowing following disagreements with Khartoum - production was halted for almost a year.

'Tip of iceberg'

The cases that are coming forward are just the "tip of the iceberg", fears Ibrahim Wani, who heads the human rights division at the UN mission in South Sudan.

South Sudan fought a long civil war before achieving independence from Sudan three years ago.

During that quest for autonomy, there were few reports of sexual violence.

Now, as South Sudanese soldiers fight each other, buttressed by other militias, it seems that sexual violence has taken on a "dimension of revenge" and "it has become rampant", Mr Wani says.

In Bentiu, the capital of oil-rich Unity state, which has changed hands between rebels and government forces four times in recent months, we found the strongest evidence yet of orchestrated ethnic attacks.

BBC Newsnight obtained testimonies of men and women who listened to radio broadcasts by opposition forces, almost all ethnic Nuers.

The hospital in Leer was abandoned as troops advanced

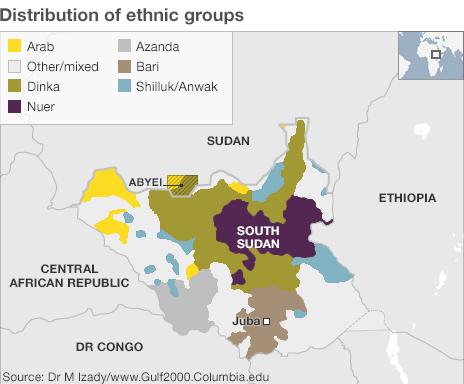

Some consider their rivals to be the Dinka community - the largest of many in South Sudan.

The rebellion was triggered by a political split in the leadership, which led to mass defections in the national army.

President Salva Kiir is a Dinka, but his former ally Riek Machar, now the rebel leader, is from the Nuer community.

On 15 April at Bentiu FM, the station manager was ordered to leave as one senior rebel commander burst in.

He confirmed to listeners the capture of Bentiu town from government forces.

'Hate speech'

A colleague claimed the Dinka and Jem - a notorious pro-government militia from Darfur in Sudan - had raped Nuer women, and now they were pregnant with Dinka and Jem babies.

The commander used the airwaves to call upon young men to meet at the barracks the following day, to go to Dinka sites, and do what the Dinka had done to their wives.

He also urged Dinkas to leave Bentiu or risk being killed.

In the language of human rights - this is considered "hate speech", albeit not on the scale witnessed two decades ago in Rwanda.

UN agencies warn that 24,000 women are now at risk of sexual violence in South Sudan, with many women exposed after fleeing into the bush to escape soldiers and rebels.

In the remote town of Leer, the main hospital run by medical charity Medecins Sans Frontieres has been trashed.

Civilians began pouring into the UN compound in Juba last year

What were once well-stocked clinics are now filled with bats.

What remains of the operating theatre is little more than a charred shell. This is where some rape survivors used to come to seek help.

All the local hospital staff fled when the soldiers advanced.

Consequently, there is no way of knowing for sure how many women have been raped here.

Michael Tang, a young man from the neighbourhood, tells me "there are many" and concedes that "for us men it gives us the desire for revenge".

But like so many other South Sudanese, he hopes that talks between the two political rivals will achieve a durable peace. A peace that will bring to an end the cycle of recrimination.

'Horrible choices'

The ferocity of the recent violence and reprisal attacks directed at civilians has forced the UN Security council to review its mandate in South Sudan.

In March it agreed to shift the focus from peace-building to the protection of civilians.

But extra peacekeepers have not yet arrived, so regular patrols along the fences of UN camps simply aren't an option, say officials.

"Yes there have been incidents which have happened right outside our gates and we have had to make horrible choices," admits Toby Lanzer, the deputy head of the UN's mission in South Sudan.

He says the mission faces "impossible dilemmas and huge logistical challenges" in a country where until recently there were barely any roads.

South Sudan celebrated independence in 2011

Activists and human rights groups are calling for greater accountability for sexual crimes committed during the conflict, ahead of a major global summit on the issue in London.

Human Rights Watch says there should be "no amnesty for serious crimes that violate international law", as peace talks continue to plod along to try to bring an end to hostilities.

'Death penalty'

South Sudan's Justice Minister Paulino Wanawilla Unango told the BBC that inciting and perpetrating rape in South Sudan would be punished "in the harshest of terms", promising that the "death penalty" could be an option if those responsible were found.

But South Sudan doesn't have the means, or the institutions ,to gather evidence to successfully prosecute sex crimes.

So some form of "hybrid" international tribunal may have to be considered in future.

But, for the time being, other priorities are likely to dominate in South Sudan.

Among them staving off a potential famine, with more than a million hungry people displaced.

Fighting erupted in the South Sudan capital, Juba, in mid-December. It followed a political power struggle between President Salva Kiir and his ex-deputy Riek Machar. The squabble has taken on an ethnic dimension as politicians' political bases are often ethnic.

Sudan's arid north is mainly home to Arabic-speaking Muslims. But in South Sudan there is no dominant culture. The Dinkas and the Nuers are the largest of more than 200 ethnic groups, each with its own languages and traditional beliefs, alongside Christianity and Islam.

Both Sudan and the South are reliant on oil revenue, which accounts for 98% of South Sudan's budget. They have fiercely disagreed over how to divide the oil wealth of the former united state - at one time production was shutdown for more than a year. Some 75% of the oil lies in the South but all the pipelines run north.

The two Sudans are very different geographically. The great divide is visible even from space, as this Nasa satellite image shows. The northern states are a blanket of desert, broken only by the fertile Nile corridor. South Sudan is covered by green swathes of grassland, swamps and tropical forest.

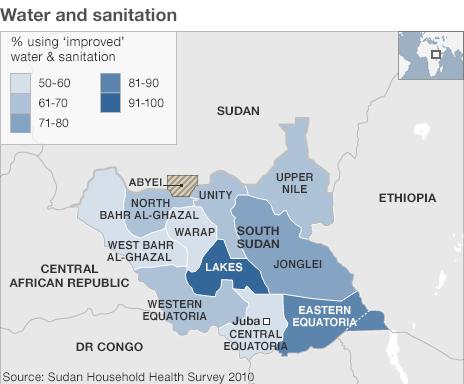

After gaining independence in 2011, South Sudan is the world's newest country - and one of its poorest. Figures from 2010 show some 69% of households now have access to clean water - up from 48% in 2006. However, just 2% of households have water on the premises.

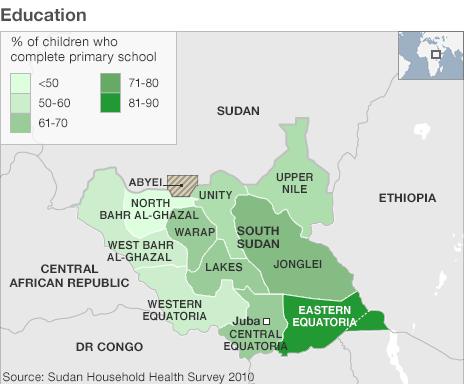

Just 29% of children attend primary school in South Sudan - however, this is also an improvement on the 16% recorded in 2006. About 32% of primary-age boys attend, while just 25% of girls do. Overall, 64% of children who begin primary school reach the last grade.

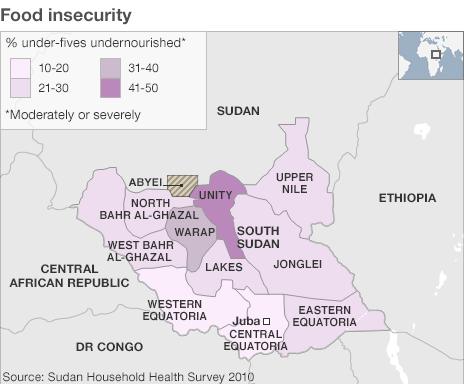

Almost 28% of children under the age of five in South Sudan are moderately or severely underweight. This compares with the 33% recorded in 2006. Unity state has the highest proportion of children suffering malnourishment (46%), while Central Equatoria has the lowest (17%).