Ivory Coast's football factory

- Published

Issa Traore (L) and Eugence Kouadio (R) hope to play in the next World Cup

Ivory Coast play their match in this year's World Cup later and most of the players will have honed their skills at a single footballing academy, from where the BBC's Tamasin Ford reports.

"So, what's the secret?" I ask 16-year-old Issa Traore as he bends down to lace up his boots.

"There is no secret," he says, laughing. "It's just hard work."

Traore has been at ASEC Mimosifcom in Abidjan, one of the most prolific football academies in the world, since he was 15.

He has two years to go before he graduates, and is aware of the immense pressure steeped on his young shoulders.

Every time he walks into his bedroom, the plaque on the door saying Yaya Toure reminds him of the legends that have come out of the academy before him.

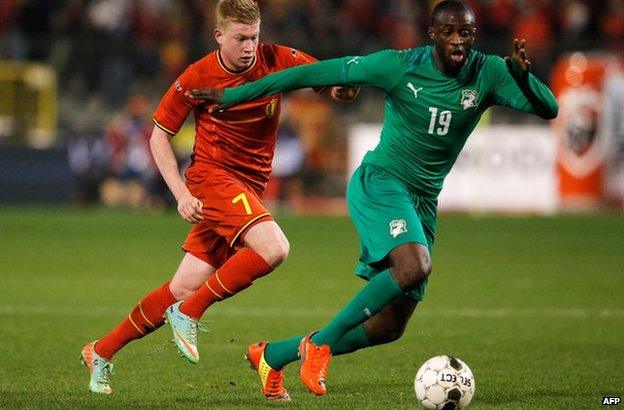

Yaya Toure is considered to be one of the best players in the world

"Yes, this was his bed," he says as he gets up, stooping so as not to hit his head on the top bunk.

"I don't know how I got it. Just lucky, I guess."

His teammate, Eugence Kouadio, 16, looks on in awe. "Yaya Toure's my idol," he says.

Not only was Manchester City's star midfielder spotted at the academy, but so was his brother, Liverpool player Kolo, as well as Gervinho, Didier Zokora, Aruna Dindane, Boubacar "Copa" Barry, Emmanuel Eboue, Salomon Kalou and the list goes on; a litany of greats who are stealing the footballing limelight across Europe.

The Sol Beni sports complex, external, where up to 40 young talents aged 13 to 18 get to train alongside the national team and the club side, Asec Mimosa, is spread out across nine hectares of land overlooking the calm but murky, waters of the Ebrie lagoon in the east of Abidjan.

It is equipped with three football pitches, two swimming pools, tennis courts, basketball courts, handball courts, a gym, a school and an infirmary where students get massages and physiotherapy.

The academy has some of the top facilities in the country

"Yes, it's really incredible here," says Kouadio.

"My family were so happy [when they first visited] because it's such a good life for me. It's difficult knowing my family is at home and I'm in this paradise."

'Next generation'

Julien Chevalier, who joined as head coach three years ago, says the academy was the first of its kind, "but we have to be realistic; now it is becoming more and more difficult".

He explains how the academy, founded in 1994 by the Asec club, inspired others across the world, adding that it is becoming harder to attract the talent.

They are "shared between competitors" and young players are spotted and "leave early", he says.

"If we want to remain the best, we must work even harder than before."

But even so, recent graduates of the academy are starting to shine at the European level, like Anderlecht's Gohi Bi Cyriac and Saint-Etinne's Ismael Diomande.

"They are the next generation," Chevalier says.

Drogba is one of the few top Ivory Coast players who did not attend the academy

And the hunt for the next Didier Drogba is ongoing.

Every year, the academy scouts trawl the neighbourhoods of towns and cities across Ivory Coast observing up to 7,000 kids a week.

"So, who here is the future Drogba?" I ask.

He smiles. "Even if I had one, I wouldn't give you his name," he says.

But he nods towards Traore, suggesting the young defender is definitely one to watch.

We walk across the vast green playing fields: dream terrain for these young players who started out playing football on grubby, brown coloured sand in their neighbourhoods.

Both Traore and Kouadio were spotted playing football in Abobo, a sprawling slum in the heart of the city where wealth and poverty lie side by side.

"It's a hard life where we come from," says Kouadio.

More than half of the Ivory Coast team which qualified for the World Cup went through the Asec academy

We reach the canteen where the younger ones are still busy having a breakfast of rice and stew after their morning training session.

From 05:45 to 22:00, five days a week, every hour of the day is meticulously laid out: football practice, fitness sessions, school, study time and then bed.

"This is a sports centre for the footballers of the future," says Adou Kouakou, head of the education at the academy.

"But education has to come with it. Only with education they will become an all-round player."

What's the secret?

Emphasis is placed on core subjects like maths and French, but the teenagers also have to learn English and Spanish as well as life skills - preparation for a possible life abroad playing football.

"Everyone wants to be a professional footballer," says Traore. "But if you only focus on football and you neglect school, what if your football doesn't work out for you?"

The older players, fresh from showering, are already starting to stream into the classrooms.

"My favourite subject is philosophy because it's the language of thinking," says Kouadio.

"You find philosophy in everything," he says, adding that's why he loves Liverpool; because of the philosophy of the club.

So, could he be the next Kolo Toure then?

"It's possible. Anything's possible if you work hard," he says.

We walk towards another block of classrooms, around the library and then on to the games area beside the lagoon.

A group of boys are sneaking in a quick game of table football before classes start.

"This is much easier," laughs Traore.

I look over at the young footballers, possibly the future generation of "Les Elephants", and realise they've missed their breakfast and school is about to start.

I quickly pull Traore aside: "So tell me then - what's the secret?"

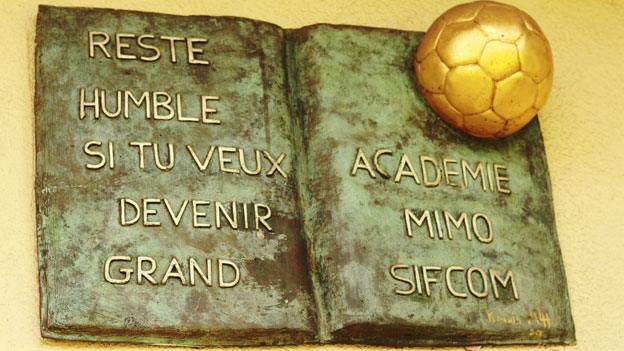

He takes me back to the school and points up at the thick, copper mounted plaque above the entrance of the computer room.

"Stay humble if you want to become great," it reads.

"That's our secret," he says, before running off to take a shower.

The academy motto is mounted above the computer room

- Attribution

- Published1 June 2014