Peter Greste represents all journalists

- Published

- comments

I first ran into journalist Peter Greste in a sandstorm in northern Afghanistan in 2001.

We were both staying in the same crowded, shabby house, trying to make sense of the fighting nearby, and clinging on to a few home-comforts - something at which Peter, with his roll-ups, his music and his well-honed ability to put the stresses of the job to one side over a few beers, excelled.

Since then, our paths have crossed repeatedly, as they tend to in this relatively tight community of foreign correspondents, cameramen and producers.

Mogadishu, Goma, Juba, Abidjan… the big stories draw us to the same hotels, frontlines, refugee camps and government offices.

Peter is a fine journalist. Over the years I have watched with admiration and surges of envy, as he has set the pace for the rest of us in places like South Sudan and Somalia.

He is based in Nairobi, Kenya, covering the continent in much the same way I try to from Johannesburg.

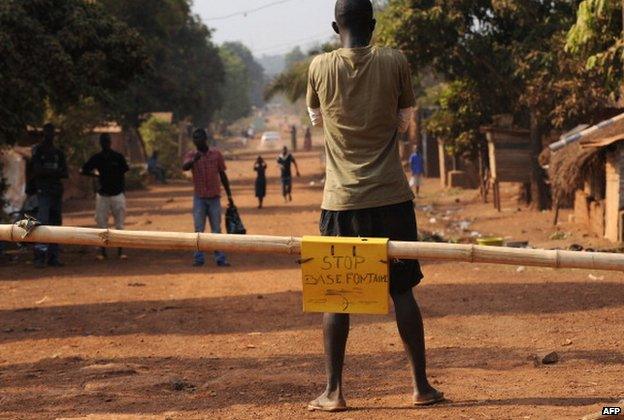

Roadblocks can cause security problems for journalists on some assignments

And yes, like the rest of us, he has run into trouble.

Roadblocks, security scares, predatory bureaucracy, and the more complicated political minefields that come with the job.

It is not uncommon, on this continent and elsewhere, to run into the assumption that foreign journalists venture into places like Zimbabwe, or South Africa, or Egypt, with fixed agendas - either personal ones or those assigned to us by our editors back home.

Regime change, cultural imperialism or just a merciless addiction to reinforcing every wretched, negative stereotype we can lay our hands on.

The truth - from my experience - is almost always far less Machiavellian.

We are just trying to find good stories, understand what is going on, give a voice to those who seem to need it most, and make sure we get our reports on air.

In 23 years on the road, I can only remember one time when an editor asked me to make changes that I did not feel were warranted - and that was in Libya, when he was more sceptical than I was about the likelihood that the rag-tag rebels would ever take Tripoli.

It is subjective stuff, for sure. We are all prone to mistakes.

Too reckless?

And with the internet, our audiences have the ability to dissect and re-dissect reports and blogs and tweets that have sometimes been scribbled at great speed and under enormous pressure.

A testy email exchange comes to mind - with a listener who bitterly objected to an infinitive that I had split on Radio 4 one morning, as I crouched behind a wall during a firefight on the outskirts of Abidjan, and which he believed fundamentally undermined the credibility of my entire report.

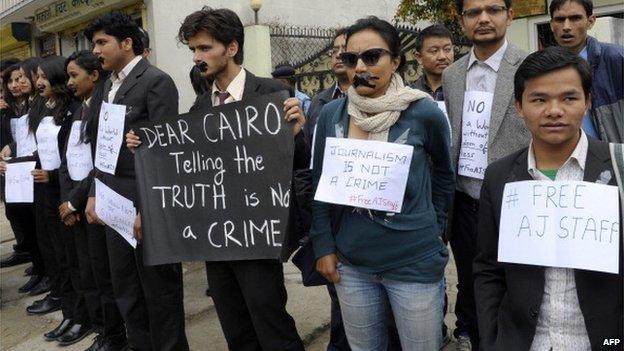

There have been protests worldwide calling for the release of the al-Jazeera journalists

But the idea - and here I realise I am being subjective, though I hope impartial - that Peter was working in Cairo in support of Egypt's Muslim Brotherhood is absurd, and appears to have been revealed as such in court to most viewers, although not, as today's sentence makes clear, to the judge.

The news is - most importantly and pressingly - a terrible blow for both Peter and his family.

But it is also something that surely strikes at the entire journalistic community.

Sometimes, when the news comes in of another colleague killed or injured in conflict, I find myself clutching at the thought that the journalist had been too reckless - had taken risks so foolish that somehow they bore responsibility for their fate.

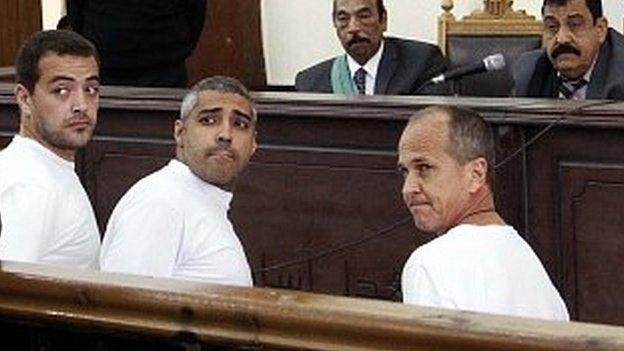

Peter Greste and his colleagues were found guilty of supporting the banned Muslim Brotherhood group

Over the years I have come to realise that this is just a self-defence mechanism - a way of trying to make it feel like that same fate could not be waiting for me on the next road in the Central African Republic or wherever.

Surely I would have been smarter. I would have pre-empted the threat. It couldn't have been me…

But what Peter's own agonisingly slow Cairo disaster has shown more clearly than any other instance I can think of is this: For however many days he and his colleagues remain in prison (and given the international outcry that must surely follow the verdict… it can surely not be many), Peter represents all journalists.

In that cage, in that cell, it really could be any of us.

Peter Greste (L), Mohamed Fahmy (C) and Baher Mohamed (R) were accused of aiding a terrorist group

- Published24 June 2014

- Published13 February 2015

- Published19 February 2014

- Published23 June 2014

- Published23 June 2014