Caring for Kenya's HIV orphans

- Published

Cheerful screams, squeaks and laughter from children welcome you to Nyumbani Children's Home located in the verdant suburb of Karen in Kenya's capital, Nairobi.

Nyumbani is a Swahili word which means home - and home is what more than 50,000 children have found here since it was founded in 1992 by Father Angelo D'Agostino.

There are between two and three dozen children in the playground swinging, sliding and playing hide-and-seek in the sandpit, which is surrounded by different houses in a well-planned and landscaped compound.

It is hard to tell that all of the children - some as young as two - are living with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which causes Aids.

"In those early years we were burying a child maybe once, twice, three times in a month," says Sister Mary Owen who now runs the home.

"We have a little graveyard which reminds us of our history.

"But now we don't have mortality here."

But it has not been a smooth ride.

Three quarters of new HIV cases are in just 15 countries

Twenty years ago not much was known about HIV and all the home could provide was quality care for dying children.

"In those early days we cared for them here until their status was confirmed, which took about 18 months," says Sister Mary.

"Today we don't accept any child who has not been definitively confirmed HIV-positive because we now have the six-week test."

She says Father D'Agostino got the first anti-retroviral (ARV) medication for the children in 2000 and that made a huge difference to them.

When Nyumbani first began it was more like a hospice for children with HIV

Drug resistance

Five years later, the home became one of the first beneficiaries of US funding through Pepfar - the President's Emergency Plan for Aids Relief.

"But we have a challenge," explains Sister Mary.

"Our children have been on anti-retroviral medication for over 10 years [and] some of them have started to develop resistance to all the drugs we are supplied by Pepfar," says Sister Mary.

That has meant that Nyumbani finds stronger third-line drugs from abroad for two of its children.

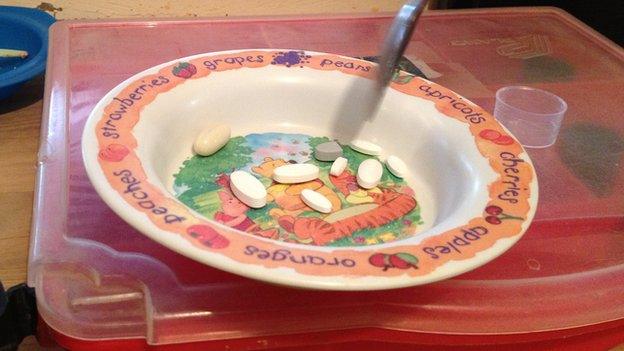

One of them, 14-year-old John (not his real name) shows me his prescription - nine pills he takes twice a day without fail.

"I want to be a pilot when I grow up," he tells me confidently, wearing a Wayne Rooney T-shirt.

"John" has to take 18 pills every day

But, he says, Cristiano Ronaldo is his favourite footballer - and he supports Real Madrid, not Manchester United.

John is growing up like a normal teenage boy, with passion for sports and a bright vision for his future.

Yet it is a future he can only live long enough to see if he continues to get the right medication.

"The major challenge is that these drugs are not supplied by the government so Sister has to source them from outside the country," the nurse who works at Nyumbani explains.

"She has to do it early enough so that we don't miss them since it's the last option for the child."

Drugs lifeline

The younger children at the home sometimes have to swallow big, bitter and hard pills meant for adults.

Sister Mary says there are not enough child-friendly ARVs.

HIV in Kenya

Adult HIV prevalence rate: 6.1%

People of all ages living with HIV: 1.6m

Children aged 0 to 14 living with HIV: 200,000

Orphans due to Aids aged 0-17: 1m

Source: UNAids/Unicef

"You see in the developed world there are so few children born with HIV that the pharmaceutical companies are not interested in manufacturing because it's in the developed world they get their profits, not in the developing world.

"So we've been using adult tablets for our children, sometimes we have to split them and we even have to open a capsule sometimes."

Pharmaceutical companies rarely develop ARVs for infants

Some scientists consider paediatric Aids a neglected disease.

Researchers from the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative say this may be hard to grasp given that in the 30 years since the Aids virus was discovered, more than 20 anti-retroviral drugs have been approved and many more are in the pipeline.

However, that is not the case for paediatric HIV.

"Children with HIV/Aids in low- and middle-income countries are not considered in the HIV research and development agenda because they are poor and voiceless and do not represent a lucrative market in the traditional sense," they wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine, external.

Titus Syengo, who heads the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric Aids Foundation in Kenya, feels it would be good if scientists in the developing world could get more involved in such neglected areas.

"Research in the developing world is still in its nascent [stage], especially for technologies. But if governments put enough money into research it can happen."

Better prospects

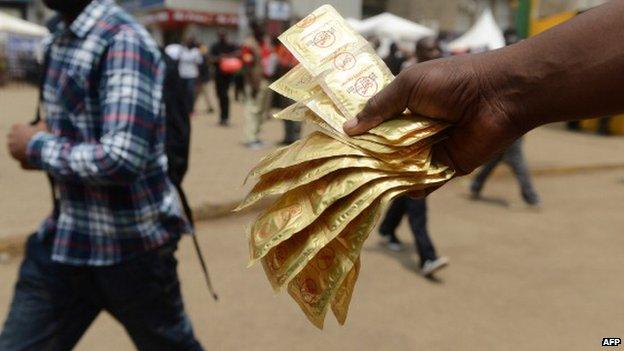

The focus at the moment is in preventing transmission of the virus from mother to child and to halt that by 2015.

With proper infrastructure and education the strategy has brought great success.

Preventing mother-to-baby transmission is the focus of global HIV campaigns

But the reality in low-income countries is that literacy levels and access to healthcare remain low and so mothers are still more likely to pass on the virus to their babies.

And Mr Syengo says lack of life-prolonging medication has dire consequences.

"If they don't get treatment, 50% of them will die by the age of two, and by five years, 80% of them will have died.

"So there's no option but to put them on treatment, otherwise you'll lose a whole generation."

The cheerful playing at the orphanage dies down as children return to their houses as evening draws in.

At six o'clock exactly, they all queue up to get their life-saving drugs - the younger ones have their medicine stirred in water and the older ones swallow the pills.

Sister Mary likes to reflect on how life has improved for the children over the years.

"One of our first boys has a wife now and they've had their first child and that child is not infected, neither is the wife.

"I thank God and I feel so happy for our children, our young people now," a beaming Sister Mary says.

- Published21 November 2013