Central African Republic's road to anarchy

- Published

People fleeing the conflict approach a checkpoint run by anti-Balaka militiamen

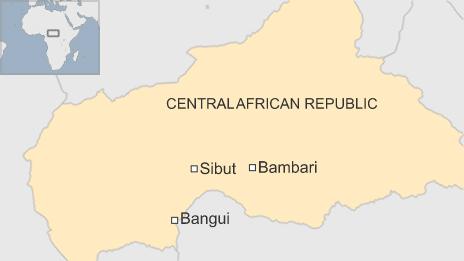

On a map, the RN (Route Nationale) 2 looks like a rather important highway linking the central town of Sibut with the entire eastern half of the Central African Republic (CAR) and beyond.

If you want to drive from the capital, Bangui, towards South Sudan, Uganda and the Indian Ocean, then the RN2 is your only option - a vital artery for commerce and migration that runs through valleys and forests, past gold and diamond mines and dozens of major towns as it forges eastwards just north of the equator and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The reality is rather more underwhelming. A sow and two piglets interrupted our journey east of Sibut. We'd covered about 60km (37 miles) in three hours, grinding along a rutted dirt track hemmed in by thick forests and head-high grass.

.jpg)

'Hidden Horrors'

The pigs - sensibly avoiding the deeper ponds swamping the road - were frolicking in one of the smaller, rain-filled potholes that marked the path ahead like glistening brown cats-eyes.

Our car slid to another shuddering stop - spare tyres piled on the roof rack - and the pigs heaved themselves out of their afternoon bath and disappeared into the grass.

Conflict erupted when Seleka rebels seized power in March 2013

About a quarter of the CAR's 4.6 million people have fled their homes

The state of the RN2 is a reminder of the poverty and uneven development that has blighted this mineral-rich nation for decades.

But it also helps to explain how the horrors currently taking place in this isolated region can remain almost completely hidden from the outside world. "Horrors" is not an exaggeration.

I'm writing this in diary form, as we push further east towards the town of Bambari, where thousands of families are seeking shelter from a new surge of violence.

Both sides have been accused of committing atrocities

Doctors in Bambari have already told me by phone that the local hospital is being overwhelmed with civilian casualties, as surrounding villages are burned and Christian and Muslim communities turn on each other once again.

But first we have to negotiate another 100km on the RN2.

'Marauding ex-fighters'

We'd been warned before we set off about "les coupeurs de routes" - the road-blocking bandits, who have taken to looting the handful of aid vehicles that venture east towards towns like Grimari.

And sure enough, we're waved down in one roadside village after another by men armed with homemade rifles and machetes.

The anti-Balaka are mainly Christian self-defence groups that emerged across much of the country last year in response to the brutal attacks of the largely Muslim Seleka rebels who briefly seized power in CAR.

CAR's religious make-up

Christians - 50%

Muslims - 15%

Indigenous beliefs - 35%

Source: Index Mundi, external

In theory, the conflict is now winding down as African Union, French and European Union peacekeepers intervene, a larger UN force prepares to replace them, an interim president pushes for new elections, and peace negotiations have this week finally produced promises of a ceasefire.

But in practice, while the capital, Bangui, may be relatively calm, much of the countryside remains in a state of seething anarchy, with far too few foreign troops available to fill the power vacuum.

"I'm pessimistic about the countryside. It's extremely volatile - and very hard for humanitarians to access. We've seen increased banditry on the roads," Claire Bourgeois, the United Nations' Humanitarian Coordinator, told me before we left Bangui.

"Cigarettes? A gift? Something to eat?" said one anti-Balaka fighter - a teenage boy with a machete tucked inside his belt - as we paused in front of another tree branch dragged across the road near Grimari.

The fighters eventually let Andrew and his colleagues pass

Fortunately for us, the fighters seemed content with the cheap cigarettes we'd stocked up on for just such encounters, and were more interested in telling us about the marauding ex-Seleka fighters they had killed on the road two days earlier. So we continued unscathed towards Bambari.

'Sounds of roosters'

It is clear though that in CAR - as in so many other conflicts - the lines between soldier and bandit have blurred and that all sides are targeting civilians.

As night fell we arrived at Grimari, 120km from Sibut. A lone French Foreign Legionnaire, standing beside two military patrol vehicles, checked our papers and waved us on.

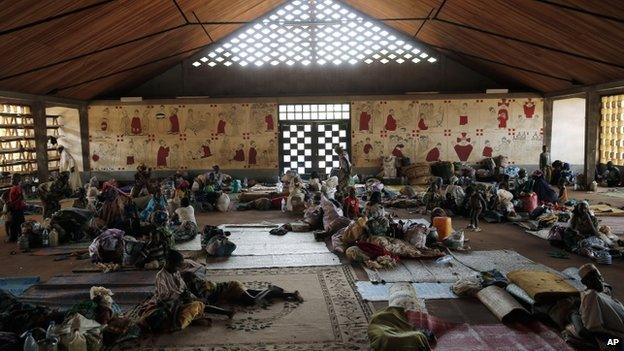

Some places of worship have been attacked...

While others have become refugee camps

"There's nothing here. You could try the Catholic church," he said, gesturing towards the dark woods ahead.

Sure enough, Father Sylvain graciously let us camp on his porch, and we woke the next morning to the competing sounds of roosters, an early morning Mass, and some 6,000 displaced civilians who had recently congregated in the church compound to seek safety.

Ordinarily, we would have stopped to talk. But we knew worse was ahead - that the rains and the "coupeurs de routes" could block us at any moment - and so we got back on the RN2 for the last 80km to Bambari.