Ebola voices: Fighting the deadly virus in Guinea

- Published

The world's deadliest outbreak of the Ebola virus has so far killed more than 670 people across West Africa. BBC News travelled to Guinea to meet some of those involved in the fight against the outbreak which, health experts say, will continue into next year.

Healthcare worker: Adele Millimouno

"At the beginning with all the rumours that were flying about we were very much afraid, but now we have adapted to the situation. We are working for our own community and we are working to save our community.

Now I feel very proud. By our work, our contribution, there are people who have walked out of this hospital cured - between 30 and 40 people.

At the beginning my family was very worried about me, given the risks in working in this kind of a place, but I always assured them that we were well protected.

In this emergency Ebola centre I have learned a lot of things, for example how to diagnose, and how to treat the patient and how to know the difference between a suspected case and a real case.

Lots of people died in front of me. It was a very difficult time for me especially when young children died. Sometimes I went outside and cried.

Some people before they die, we hold their hands, we touch their heads, we sit by them for a little while."

Survivor: Saa Sabas

Ebola survivor: "I was asking myself whether I was going to live."

Scientist: Andrew Bosworth

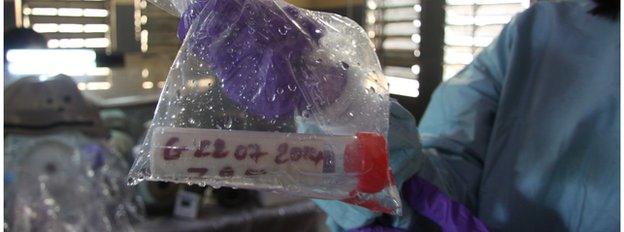

"At the beginning of the outbreak there were a lot more patients around - the sample numbers being seen by the lab were quite high, and a lot of those were positive.

Some days we see around 15 samples. We are still seeing positives, but increasingly we are seeing negatives here.

When you see a negative case from a patient that was previously positive then it's a bit of a celebration because you know that that person is feeling a lot better and might even be released soon. Sometimes you see patients being brought in that are very young and they are testing positive and that's very sad.

For the Ebola virus the fear element is the thing which is causing problems in the community and in the recruitment of health staff to help with the outbreak itself.

Ultimately it is spread in a very specific manner, by close contact with patient fluids, blood and at the end stages when the body increases secretions of saliva and sweat. Having that in your head whilst you are dealing with these samples is obviously very important because the risk can be mitigated through very simple but carefully prepared measures."

Red Cross co-ordinator: Mathew Schraeder

"When I first arrived on the ground in Gueckedou people were not willing to allow access to humanitarian workers to come in and deal with cases or allow contact tracing.

It's been steadily declining since then in terms of numbers - there's the odd small spike, but the main issue we have been facing over the last weeks has been reticent villages still not willing to allow us access.

So we have been making strong efforts to do a lot of communication, a lot of sensitisation.

There is a level of frustration in Guinea that I haven't experienced in a long long time - not just reticent populations; it's a lack of co-ordination.

We can deal with cholera outbreaks all over the world. Ebola is a big scary monster and yet we are not quite sure how to quite deal with it."

Anthropologist: Sylvain Landry Faye

"I investigate first the rumours, perceptions and attitudes of communities relating to Ebola fever in order to help the communication team. I also help the medical team interact with communities in the villages to break down barriers.

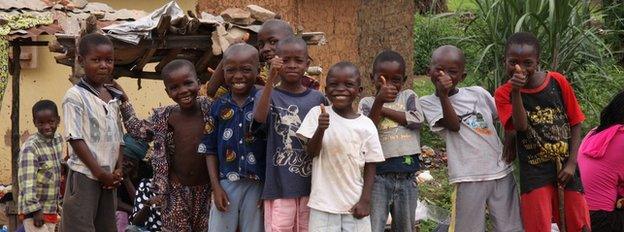

People are very very afraid, because they have never heard of Ebola before.

We have many rumours, for example, that the fever was disseminated by [Guinea's] President Alpha Conde because he is from another ethnic group.

The villages are in remote areas where there is little access to news and the level of education is not high.

We have changed our approach in order to allay their fears. The medical team used go first to pick up patients; now they wait for us.

We use community leaders and community healers as well.

It has changed - they now are the first to call us, we tend to be in villages because they want us to be there, because the approach is different."