In pictures: Darfur refugees then and now

- Published

Residents of camps in Sudan's war-torn Darfur region photographed in 2007 explain how their lives have changed seven years on.

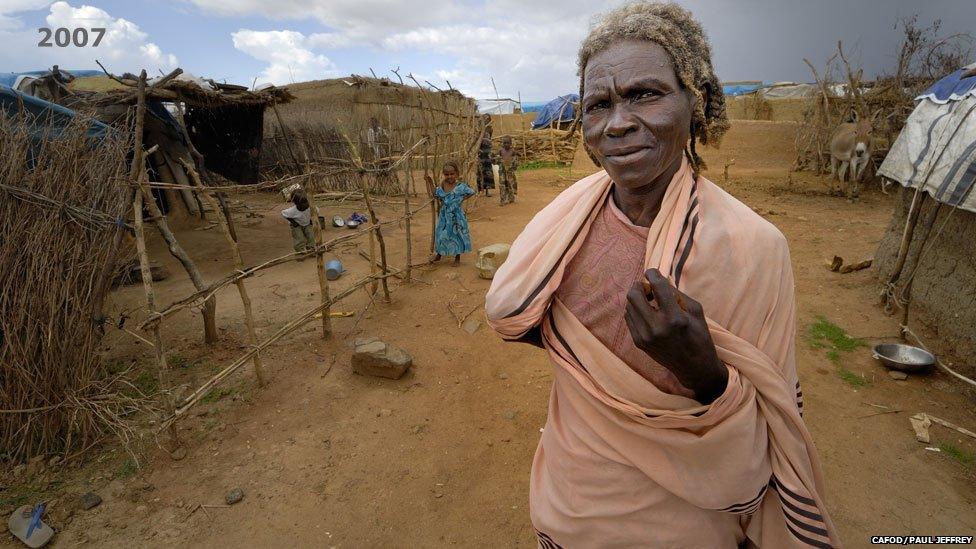

More than a decade since conflict erupted in Sudan's western region of Darfur, the more than two million people who fled their homes have little prospect of returning to their villages. Photographers for the Catholic aid charity Cafod pictured people at three camps in central Darfur in 2007 and again in 2014 to find out how their lives have changed. "I don't remember the day they took this photo, but I had more hair then," says Hamisa, the only camp resident photographed who was happy to use her real name. "I no longer have my peach toub [traditional dress], it burnt in a fire."

Hamisa remembers fleeing her village in 2003 "carrying one of my grandchildren on my back" when it came under attack. "We hid in the mountains and when the 'pow pow' [guns] were silent, I came back to the village and helped to bury some of the dead." It took the villagers four days to reach the Hamadia camp. "I never thought I'd be here for 11 years [and] never to see my village again. When you look at me now, you see an old lady, and because I'm old I can speak my mind, and I ask world leaders to bring back peace to this land, for the sake of our children."

Farming is the traditional way of life for many rural Sudanese. But those forced from their homes because of conflict lose their land, livestock, tools and seeds. Many camp residents over the years have relied on food aid. With only a few international aid agencies still able to operate in Darfur those that do, like Norwegian Church Aid, are trying to support camp communities to become more self-reliant. Here a co-operative from Hamadia camp farm a 15-hectare plot of land.

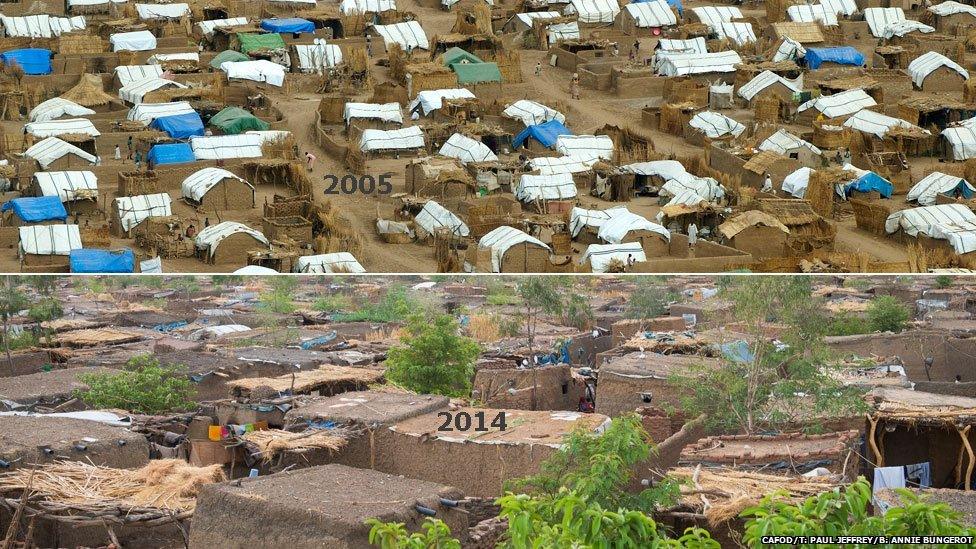

There are more than 27 camps in Central Darfur, from small camps of a few thousand to larger camps hosting around 70,000 people. These photos of camps near the town of Zalingei show how things have changed over nine years. Tarpaulin roofs have been covered with mud bricks as homes have morphed into permanent settlements. There are narrow alleys between tight-packed makeshift houses that sit higgledy-piggledy on top of each other - and the trees have grown to provide much-needed shade.

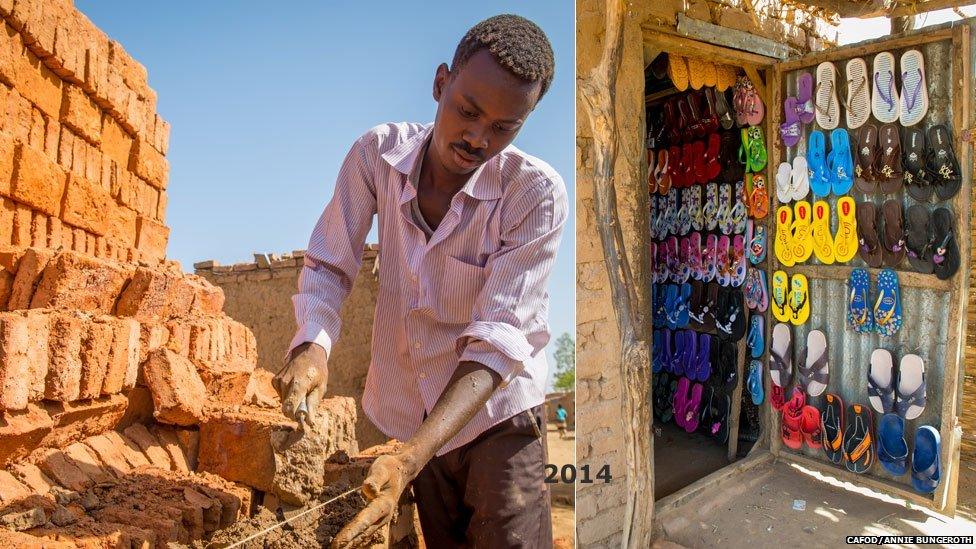

There are signs of permanency everywhere in the camps: Shacks selling basic supplies; piles of roughly made red bricks waiting to be to be used to build more sturdy structures. It takes two days to make 1,000 bricks which sell for 40 Sudanese pounds ($7; £4) - the average daily labour rate is two Sudanese pounds.

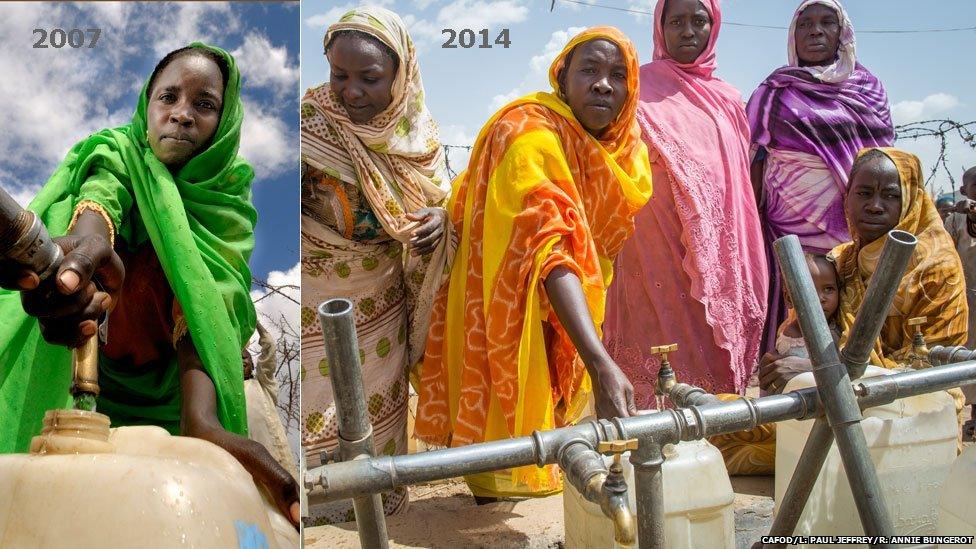

Amina, seen in green to the bottom right of the photograph, remembers seven years ago staring down the gaping hole of the newly dug well. She had gone with other women to the site in Khamsa Dagiag camp with food for the men digging the foundations. Solar panels now provide the energy for a pump to provide 15 standpipes in the camp from the well. "It was the best day when we had our own water in the camp," says Amina. "Before, we had to walk to the valley to collect water, and this was dangerous, because we were threatened by nomads who would attack us."

"We still face many challenges after 10 years of living here, but at least we don't need to worry about fetching water," says Amina, whose nine-year-old son was born in the camp. He is now going to school and she hopes he will use his education to find a better life outside the camp one day. Amina does not read or write and sometimes goes to Zalingei to earn money by washing and ironing at "big houses" in the town.

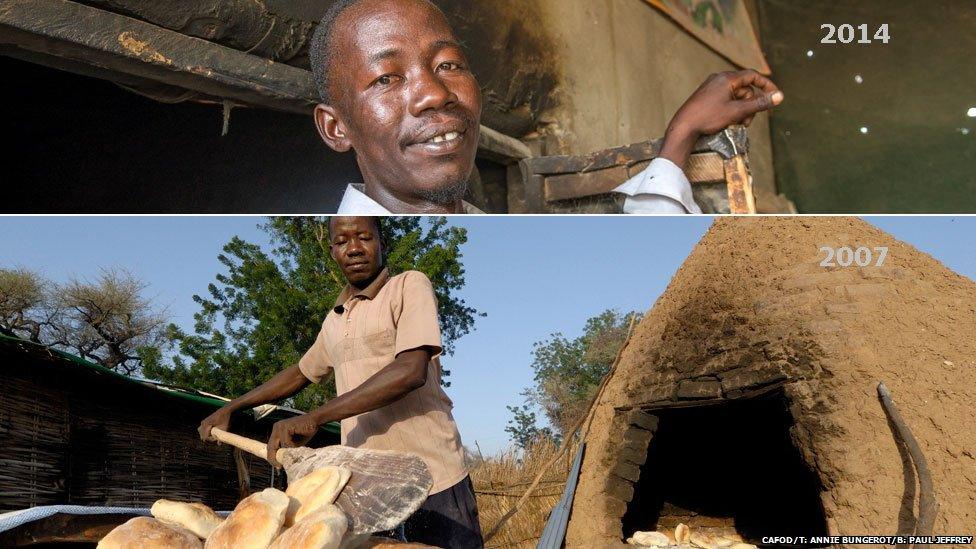

Finding work in the camps can be difficult. In 2007, Yousif was single and on arriving at the camp had learnt how to bake bread to support himself. Today he is married with three children. "I moved to a different camp when I married - it has no prospects for me to bake bread, so I took up brick-making. It's hard work, but I need to take care of my children," he says. "Darfur is still not secure, so I can't take my children back to my village and show them a peaceful life."

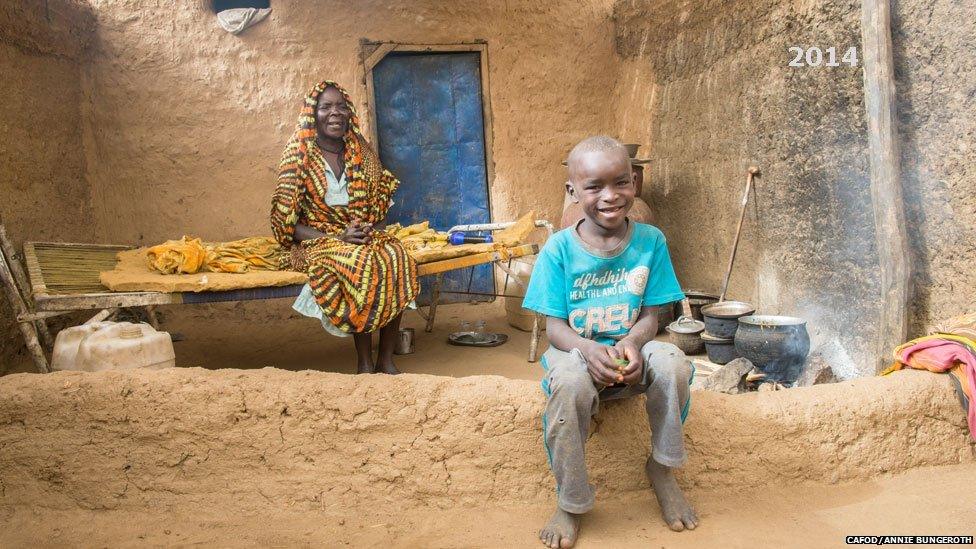

Haja was pictured here in 2007 with the youngest of her seven grandchildren, Horan, in Hassa Hissa camp. "I was living in sector two of this camp when the photo was taken - the place was too small for us so we moved," she says. Haja would like to go home but feels this is unlikely and she has lost contact with neighbours and village friends. "In my village we could provide for the children, we had fields to farm, livestock and milk," she says.

Seven years on and besides moving house, life has not changed much for Haja. "I look after my grandchildren while my daughter looks for casual work in the town - washing dishes or ironing clothes," she says. Horan is now attending a Koranic school. The older grandchildren go to other schools in the camps. There is now a whole generation of children who have known nothing except camp life.

When Rawia fled her village, she arrived at the camp with her husband and children carrying only her jerry can and a small amount of food wrapped in a cloth. It took her several days before she was reunited with her parents, brothers and sisters. "My mother recently passed away, and we have buried her here in the camp," says the 32-year-old mother of four. "We could not take her back home for burial because we still receive news of fighting; my heart is heavy because of this."

The conflict in Darfur is being waged on many fronts and by different groups; fighting between government forces, rebels and militias, and localised conflict that has sparked a wave of inter-ethnic violence. This meant there is a steady flow of new arrivals - on foot, donkey and hired vehicle. According to the UN, 390,000 people fled their homes in the first half of 2014 - more than in any single year since the height of the crisis in 2004.

A 2011 peace initiative has failed to stem the conflict, which has become more complex than the historical tensions between the mostly nomadic Arabs, and black African farming communities over grazing rights. The joint UN and African Union force deployed to the region patrols the camps in armoured vehicles and some people feel insecure about leaving the camp. Residents have been forced to find new ways of earning a living - but there is a burgeoning entrepreneurial spirit.

And traditional ways of life continue inside the camp. Here a henna artist works on a design for a client. Sudanese women like to decorate their hands and feet with henna for festivities, especially weddings. "Life is difficult in the camps, but when we come to do our feet we forget about our problems," said one of the women.

Community leaders (L) still expect to maintain their authority in the camps, but worry that frustration at the lack of proper jobs is leading to an increasingly politicised younger population that is vulnerable to recruitment by militia groups. Youth committees have been set up to engage younger camp residents - football is popular with young men and there is growing interest in volleyball among some young women. Gallery from Cafod; photos by Paul Jeffrey and Annie Bungeroth