Ebola outbreak: What Uganda can teach West Africa

- Published

The experience of health workers in Uganda may prove to be instructive for other African nations dealing with an Ebola outbreak

Dr Jackson Amone, who has tackled several Ebola outbreaks in Uganda, volunteered to go to West Africa to help his counterparts with the growing crisis in the region.

"Where duty calls you go," he told me from his small office packed with papers in the capital, Kampala, before he left.

Our appointment was for 07:30 local time. I arrived 10 minutes early, and he was already working.

"Mentally, you have to be trained first and also practically you need to know, what are you going to do… you use your past experience to protect yourself."

What did his family make of his decision?

"You have to convince them," he replied.

Dr Amone has treated many Ebola patients and led national response teams in the East African nation, which has become a hub for Ebola experts.

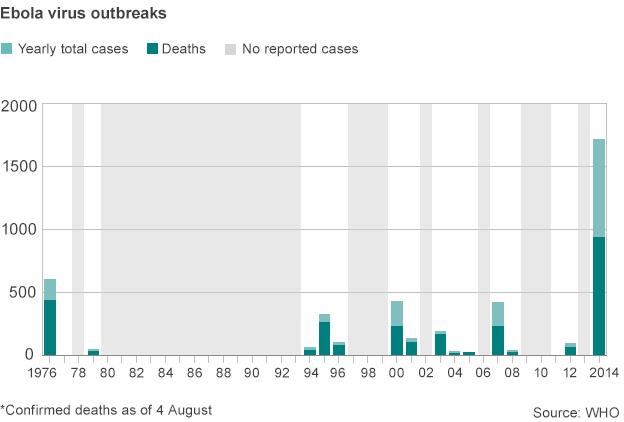

Before the epidemic in West Africa, the worst outbreak was recorded in Uganda in 2000.

More than 425 people contracted the virus, mainly in the northern town of Gulu. More than half of them died.

Since then there have been four more outbreaks.

In addition to that, Uganda has had to fight similar viral haemorrhagic fevers like Marbug, Crimean Congo and Yellow Fever.

But the government has managed to stop widespread Ebola outbreaks.

During the last one in Luwero, central Uganda, there were seven cases and four deaths.

Medical app

What can Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea and Nigeria learn from Uganda's experience?

The importance of speed cannot be underestimated.

Uganda now has a laboratory that can test for Ebola and other haemorrhagic fevers

Spotting cases quickly, confirming them as Ebola and sending out teams.

At the Uganda Virus Research Institute, overlooking Lake Victoria, in the sleepy town of Entebbe, a small laboratory has been set up to do this.

With the help of the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) scientists are receiving Ebola results out within 24 hours.

Stephen Balinandi is a laboratory specialist at CDC and has worked on many of Uganda's outbreaks.

"Unlike before when specimens would be shipped to international labs like the US, we are able to test specimens here within a short time," he says.

"And we send back the results to the healthcare givers in the field, who are able to properly manage the patients."

But any one of the scientists at this lab will say that their work is futile unless suspected cases can be picked up to begin with.

To this effect, the health ministry has educated health workers and the general public on Ebola symptoms.

A young team of techies has also created a health monitoring system known as mTrac that helped with the last Ebola outbreak.

Using a basic mobile phone, health workers reported suspected Ebola cases and received information on how to help communities.

Kissing 'joke'

Over the last decade, their response to outbreaks has improved immeasurably, Mr Balinandi says.

In earlier outbreaks, medics were forced to rely on little more than a hunch.

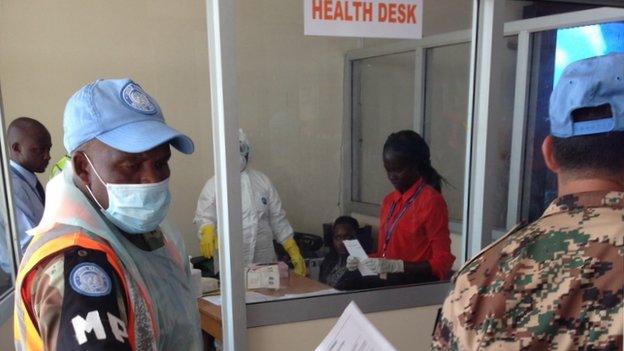

Entebbe airport in Uganda has set up Ebola screenings in response to the West African outbreak

"After very many people had died - then there would be suspicion that we are dealing with something," he said.

Now testing is done earlier in order to pinpoint an outbreak.

Public information campaigns are also vital.

During an outbreak, messages are sent out telling people how to spot potential Ebola patients and how to stop themselves from catching the virus.

This starts at the local level, where leaders and social mobilisation teams go out to speak to those in the affected communities.

And, on the national stage, the president himself has been known to get involved.

In 2012 when there were Ebola cases in western Uganda he made a statement telling Ugandans not to kiss or shake hands.

It quickly made the headlines, and although it became a joke, he got his message across.

The public understood that limiting close contact was vital.

Local authorities often act quickly closing schools, markets and burying suspected Ebola victims to avoid gatherings.

Many Ugandans will admit that their national health system is somewhat lacking, with cases of women dying in labour, drug shortages and poorly resourced health centres.

But the fact that public health officials have managed to stage effective responses despite the many limitations should provide an example for the governments in West Africa, which face similar challenges.

Dr Amone, who has now arrived in Sierra Leone, feels the first crucial steps that would have limited the outbreak there were missed.

"The fact that you need to accept that Ebola is with you at the beginning is very important, because now the thing has spread out, we're going to have to do fire fighting."

Ebola virus disease (EVD)

Symptoms include high fever, bleeding and central nervous system damage

Fatality rate can reach 90% - but the current outbreak is about 55%

Incubation period is two to 21 days

There is no vaccine or cure

Supportive care such as rehydrating patients who have diarrhoea and vomiting can help recovery

Fruit bats are considered to be virus' natural host