Letter from Africa: Ebola is not an African problem

- Published

- comments

In our series of letters from African journalists, film-maker and columnist Farai Sevenzo considers the difficulty in finding funding to fight an international public health emergency.

Who remembers February 2014? By its very stunted growth, February can be a forgettable month.

But it was in February that a haemorrhagic fever announced its presence in Guinea, and now the number crunchers in officialdom are reeling off figures in the thousands for those affected and killed by Ebola.

In the nine months that have nearly passed, the world has been slow to act.

We are fond, in the reporting profession, of spinning a story for maximum impact but there is simply no spin to the Ebola invasion - it is a crisis of unimaginable proportions.

Disaster emergency funds have not been sufficient to combat a virus which has made a mockery of disaster preparedness.

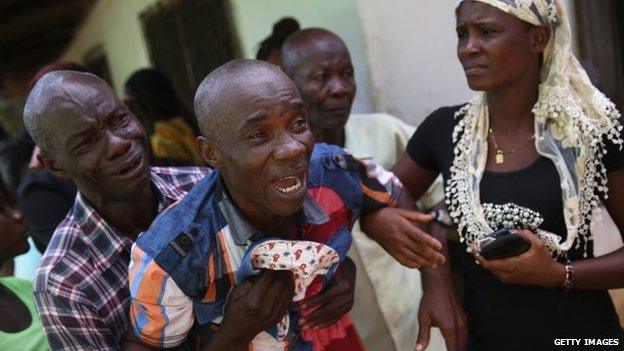

I've made the calls to friends in Monrovia and Freetown, where the individuals feel their fate is in the hands of the Gods not just the brave medical professionals on the front line.

Most airports in the world have someone pointing a body temperature reader at you, especially if you have recently set foot in Africa.

And as everyone knows, Africa is one country to the very impressionable and the far less travelled.

But Ebola has not been reading passports, and health care workers from many nations will tell you that the disease does not discriminate.

It is puzzling then to watch the world reaction to Ebola's relentless grip.

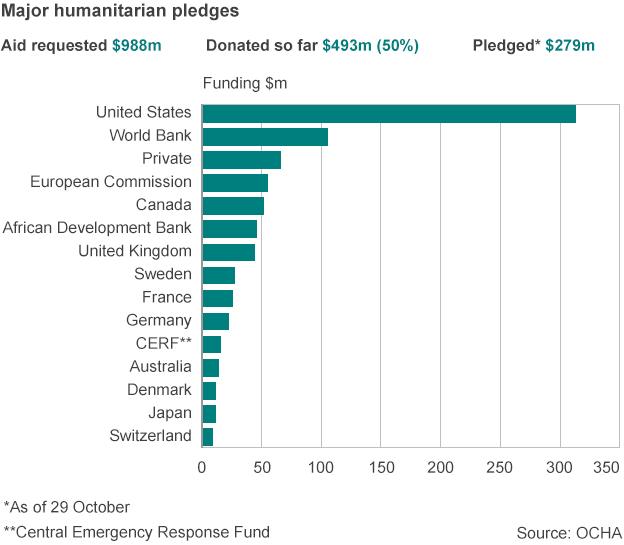

Back in September, Ban Ki-moon launched a UN fund and said nearly a $1bn (£620m) was needed to fight Ebola for the next six months to try and get a grip on it before February comes around again.

Resolutions were passed and the world made all the right noises.

But the newly established UN fund to fight Ebola remained running on empty.

A second appeal did not fare much better - with only about 10% of the total pledged so far, external.

Amidst the complacency, we read that fear and ignorance of Ebola is causing panic and hysteria, with West Africa visa bans and African footballers on international duty being "monitored" - despite never having kicked a ball in an Ebola ward.

Those states from whom much is asked are either under the false illusion that such measures will be enough, that the virus is not their problem or they are simply choosing to shirk their responsibilities.

There is always room to raise the racism flag, but it would hardly be worthwhile for the realities are stark - if Ebola is not stopped at its current source in West Africa, no country will be safe.

'Custom made to travel'

We are living in those times of great migration - where a two-year-old can cross a border into Mali, travel 700km (430 miles) on several buses and then die from the Ebola virus and possibly infect countless people.

Where a man on a flight can reach Nigeria in the confined space of an aeroplane, then die of his illness and fatally infect the doctor who had the foresight to keep him contained.

Then there are the people traffickers, the porous borders - Ebola is custom created to travel.

Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone are the three countries in West Africa worst-affected by Ebola

I am writing this in an African city far to the south of the epidemic, where while passing through two different countries, immigration officers asked me if I had been to West Africa in the last four weeks.

Of course there are many parts to West Africa but that seemed irrelevant.

I hadn't been to any of West Africa's 15 states and said no.

There is a wind of panic in the air and the reaction to Ebola remains uncoordinated.

Ebola virus disease (EVD)

Symptoms include high fever, bleeding and central nervous system damage

Spread by body fluids, such as blood and saliva

Fatality rate can reach 90% - but current outbreak has mortality rate of about 70%

No proven vaccine or cure

Fruit bats, a delicacy for some West Africans, are considered to be virus's natural host

Tanzania's Citizen newspaper reported last week that despite a new bio-safety laboratory in Bagamoyo, the nation would be unable to test for Ebola because it lacked approval from the World Health Organization and that funding was needed to supply reagents - a substance used in chemical analysis.

While in Zimbabwe's Sunday Mail, an official raised concern over a report that suggested the country has 57 informal border posts as opposed to 19 official ones, and what that would mean in the Ebola era.

And as the World Bank appeals for volunteers in the Ebola fight, Australia's government has said it will not send doctors or nurses to help contain the virus until it is certain "all of the risks are being properly managed".

Protective gear is essential for those treating Ebola patients

But many have volunteered. Cuba and Zimbabwe have sent doctors to Monrovia, the Americans are in Liberia, the British in Sierra Leone, the French in Guinea and there are individuals of astounding personal courage sweating in protective plastic suits in the heat of West Africa - yet that is not enough.

The rallying cry before the outbreak had been "Africa is Rising", and now fragile health care systems have been crippled beyond measure.

Could a dollar from each of us build hospitals in Kenema, provide more beds in Monrovia and contribute to quicker detection methods?

Oh for a Nelson Mandela to kick some proverbial backsides and get Ban Ki-moon's UN Ebola fund up to speed.

Once upon a time the world dismissed Aids as a disease for Africans, gay men and drug users. Over three decades on it is still with us in every corner of the globe.

Ebola is not an African problem; it may come for all of us wherever we are.

If you would like to comment on Farai Sevenzo's column, please do so below.