Ebola crisis: Volunteers for a hardship mission

- Published

Thousands of volunteers are required to combat Ebola, as Imogen Foulkes reports

In the tranquil grounds of the Red Cross in Geneva, a group of people are struggling to put on rubber overalls, face masks, goggles and not one, but two, pairs of gloves.

They are training for what one of their supervisors describes as "a unique hardship mission."

These are health care workers, doctors and nurses, who have willingly volunteered for deployment to Ebola-affected countries, a job they all know carries risks.

Leah Feldman, an emergency ward nurse from New York City, is among them.

"I feel as though it's a responsibility," she says. "I have a set of skills that I feel I can offer. I really feel as though this is a region that deserves our attention right now. I think medical care is something we can provide that can actually make a difference in lives where oftentimes there is not adequate medical care."

Ms Feldman says that, despite the high-profile cases of a few health workers who have been infected with Ebola, she is not worried about risks to her own health.

"That's the first question people ask," she says. "But no. [There are] protocols and rules to minimise the risk, and it's my responsibility to stay as safe as I can."

Painstaking regime

Part of Ms Feldman's responsibility, before ever setting foot in an Ebola-affected country, is to take part in the Red Cross training course.

Leah Feldman, one of the volunteers, says she "can't wait" to join the fight against Ebola

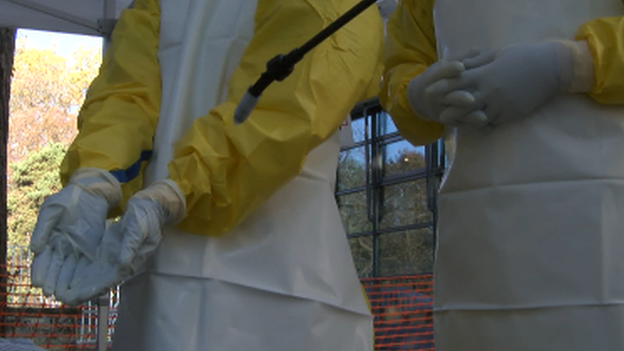

Particular attention is paid to the eyes, nose and mouth as Ebola is spread through bodily fluids

Some items, like gloves, need to be disinfected twice

It is a painstaking, uncomfortable and often depersonalising regime, which regularly requires the volunteers to abandon many of the things they learned in their original medical training.

Before even entering the anteroom to the Ebola ward, the volunteers have to put on several layers of protective clothing. Watched by an experienced supervisor, each item has to be put on in the correct order and the correct way - no loose sleeves or cuffs. Ebola is spread through contact with body fluids, so the skin, and above all the eyes, nose and mouth must be covered.

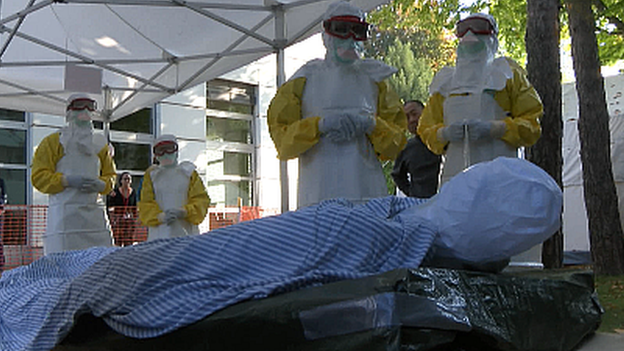

"The interaction that is so important for nurses and doctors with the patient is almost completely absent," explains Red Cross Emergency Health Officer, Panu Saaristo. "We are wearing the protective equipment, people look like aliens, you don't recognise their faces."

Working inside those suits is uncomfortable too, as Leah Feldman discovers. "It's hot and claustrophobic in the suit," she laughs. "And here I'm in Switzerland, so I can only imagine what it will be like in Monrovia."

Slow down

One of the hardest things the trainees have to learn, says Panu Saaristo, is to take every step slowly.

"People from western health care settings are used to always being in a rush," he explains. "They run from patient to patient. This is probably the only workplace they will experience where you never are in a rush, because everything is focussed on safety and infection prevention."

That focus means that just taking off the protective clothing takes a minimum of 15 minutes, with frequent pauses to re-disinfect particular items, such as gloves.

"I'm used to moving at a very fast pace," admits Leah Feldman. "I think the hardest part here is going to be moving very slowly, very meticulously, and just paying really close attention to every action that you are making."

The smallest mistake when getting dressed could mean the volunteer gets infected

Wearing full gear, "people look like aliens", said one Red Cross worker

The precautions required leave little room for intimacy between medical worker and patient

But, once in the field for real, Panu Saaristo knows from his own experience, working with Ebola patients will take a psychological toll as well.

"There are a lot of deaths," he explains. "Sad scenes with a lot of children separated from parents, and parents separated from children."

"You won't get a hug from your colleague," he continues. "You don't shake hands, you don't share anything, you don't even share a simple thing like a pen. It is draining, and that is what I mean when I say this is a difficult mission."

Ebola Stigma

Perhaps most difficult of all for the volunteers, the recent cases of Ebola in some of their home countries, such as Spain and the US, means they now fear stigmatisation once their work with Ebola victims is over.

The moves by some American states to quarantine returning health workers is causing aid agencies like the Red Cross real concern, because they fear it could deter future volunteers, who are desperately needed in the Ebola affected countries.

"There have been some almost absurd reactions," says Mr Saaristo. "Misconceptions, fear, stigma, explanations that are not based on science."

Those who volunteer could face stigmatisation when they return home

"We have to try to combat that in the home countries of these volunteer healthcare workers."

Leah Feldman does not know what her reception will be when she returns to her native New York, but diplomatically says she is "more than willing, if the government makes certain decisions it thinks will protect its own people, that's something I will of course abide by, any protocols and regulations."

But she adds, "It's about knowledge, it's about teaching people what Ebola really is, and how it is actually transmitted."

Training over, Ms Feldman can expect to be treating Ebola patients for real within the next couple of weeks. Undeterred by protection measures which have certainly frightened off some potential volunteers, she says she "can't wait to go."

"If it's not something you feel comfortable with then it's not for you," she says. "But if you feel you want to help people, this is the closest you can come, where there is a need you are filling that void."