In pictures: Ebola orphans

- Published

The Ebola outbreak in parts of West Africa has left more than 500 orphans, with parents either dying or abandoning their children, aid agencies say.

In normal circumstances, extended families would take in orphaned children but many are now refusing to do so, they say.

"Children are sent off to extended family outside affected areas, but extended families don't want to take care of orphans of affected parents or other vulnerable children any more out of fear of being contaminated or stigmatised in the community," said Dr Unni Krishnan, head of disaster preparedness and response for Plan International.

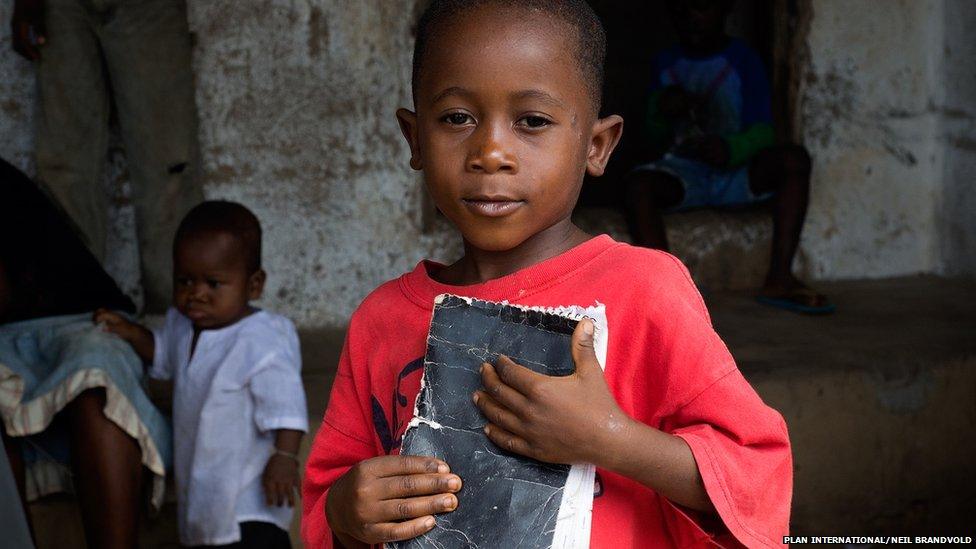

John, five, from Lofa County, Liberia lost both his parents to Ebola. When they died, no-one was prepared to look after him and his sisters because their parents had died from Ebola. Their extended family is from Sierra Leone but it has not been possible to trace them.

Siah, 16, is the oldest of three siblings and is now facing the challenge of raising her younger brother and sister. "We cry every day and night because of Mama," she says. "I can't imagine how I will take care of the children without any help. I feel very scared right now. I don't want Ebola to catch any other member of my family. I can't afford to lose any of these children to Ebola."

.jpg)

In Bomi, Liberia, Miatta, 16, Jenneh, 12, Musa, five, Larmie, one, and Hawa, six months, are the only remaining members of their family. They lost both parents to Ebola. Miatta is now raising her brother and two sisters along with her son Larmie. "When my mother was sick, they came for her," she says. "I was scared and thought they were spirits because of the clothes they were wearing."

"When day breaks, I cook dry rice, and [we] eat," says Miatta. She says the health ministry gave them 30 cups of rice when their mother died, but they have not received any more food from the government. "I want to be a president in the future," she adds. "When I become president, I will make sure that things will become accessible like rice and medicine."

Musa and his siblings are sometimes given food by churches or community members. They are trying to keep themselves safe by washing their hands regularly, but they have little money, which they need to buy chlorine for the water.

Also in Bomi, Pascaline, 14, (in orange), Noami, 12, (bright green), Yonger, 11, (purple) and Blessing, two, sit on the porch of their home on the first day the quarantine was lifted from their house after they lost their parents to Ebola.

Their elder sister Fatu, 28, (pictured here braiding sister Princess's hair) says their father was the first to get sick from Ebola. "He used to work at the Ahmadiya hospital. He was treated but he didn't recover and he died. After a few days, grandma also got sick and died. Our mother also died after 14 days and then the last to die in this roll was my little brother."

Fatu says: "I'm feeling bad for several reasons. I have not been able to go to the hospital for my regular check-up as a pregnant woman because of the 21 days quarantine that was placed on their house. Also, people in the community are stigmatising us because they say Ebola is in our house. So nobody wants to have anything to do with us."

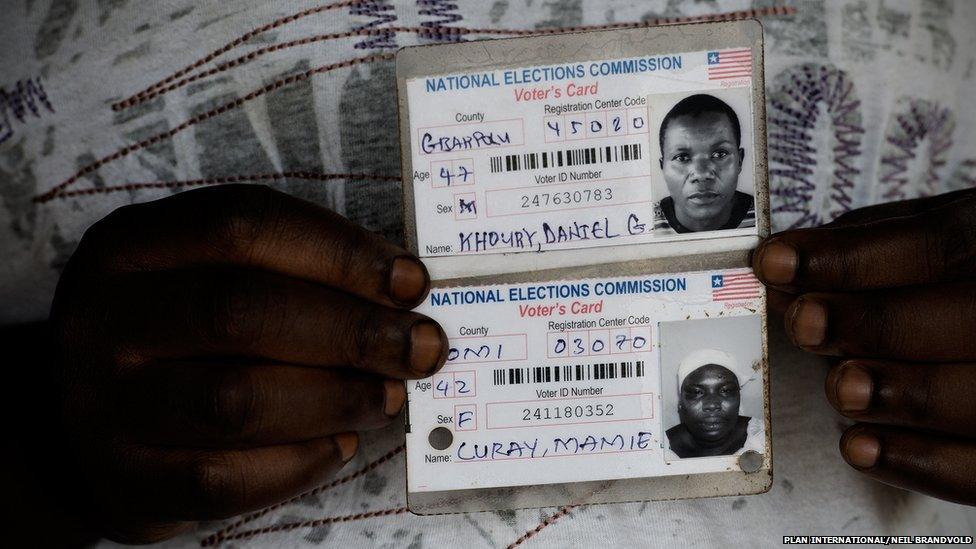

The only pictures the family has of their parents are their old voter identification cards. Fatu says: "Living like this is hard and I can't imagine what will happen to the country if things should continue like this. The health ministry only gave us food one time and that was all."