Tunisia 2.0 - from revolution to republic

- Published

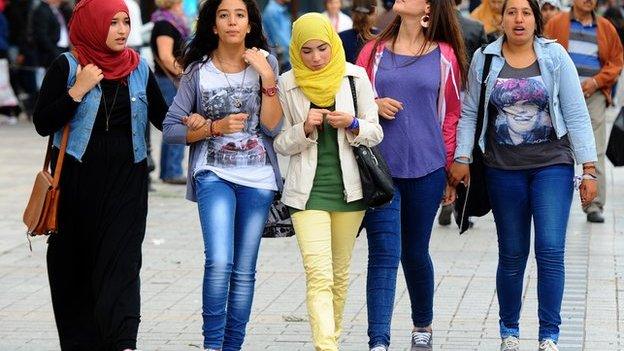

The secular-leaning Nidaa Tounes party was the most popular choice of voters in the parliamentary election

For someone who has not been sleeping much, and working punishing hours for months, 27-year old Anis Smaali is in an extraordinarily good mood.

He is running a team of 5,000 election observers for Mourakiboun - a group that monitored Tunisia's parliamentary elections in October and on Sunday will be observing the first freely contested presidential election in the country's history.

"These are the most important elections in the history of Tunisia," he says with a broad smile. "After this we will have a real government with a five-year mandate. Tunisia is showing that a real and sustainable democracy is possible in the Arab world."

Less than four years ago, Mr Smaali was among hundreds of thousands demonstrating outside the Interior Ministry, calling for an end to dictatorship.

Tunisia is leading the way for other Arab countries, says election observer Anis Smaali

The ousting of then President Zine El-Abedine Ben Ali that followed inspired young people across the Arab world.

Long-time leaders were toppled in Libya, Egypt and Yemen amid scenes that might once have seemed unthinkable.

But only Tunisia has managed a successful transition, while other countries that experienced uprisings have reverted to authoritarian rule or descended into violence and chaos, crushing the hopes of young activists.

Astonishing

In Tunisia, the most progressive constitution in the region was adopted earlier this year.

The hope now is that this election period marks the beginning of a second - democratic - Tunisian republic.

Twenty-six candidates are running for president, among them several members of Mr Ben Ali's ousted regime.

Although the presidency is now a mostly ceremonial post, many young Tunisians will see the old guard running for office as a bitter pill to swallow.

But it followed a parliamentary debate on a new electoral law in which politicians decided against a ban on Mr Ben Ali's former colleagues.

A strong nation is a nation that respects all its religious sects, says Ennahda politician Jawahra Ettis

It was an astonishing decision, especially considering that the Islamist Ennahda party - many of whose members had been tortured under the previous regime - voted against a ban.

"We, the children of political prisoners, saw the harshness of the regime on the faces of our fathers and mothers," says Jawahra Ettis, a representative of Ennahda in the outgoing parliament.

As a child, Ms Ettis remembers her father being taken away and tortured. On his release, she saw the marks where cigarettes had been stubbed out on her father's skin.

"It was a shock for me to see him so distorted, but what was even worse was the psychological torture," she says. "We lived in fear for years, but it also motivated me to become politically active."

In 2011, at the age of 26, Ms Ettis became a member of the Tunisian constituent assembly, and was later involved in drafting the new constitution.

"I am so proud of this constitution," she says. "People in the Arab world have to learn to sit down and conduct a dialogue; they have to learn the art of compromise."

"A strong nation is a nation that respects all its religious sects and political groups."

For Ennahda, part of the compromise was to allow members of the Ben Ali regime to run for office.

"We had to rely on the conscience of our people," Ms Ettis says. "If it's the will of the people that the agents of the ex-regime return, we have to accept it."

Frontrunner

Members of Mr Ben Ali's party, the RCD, are also returning to public life as members of other parties.

Nidaa Tounes, the secular-leaning party that won the largest share of seats in last month's parliamentary election, has several ex-regime officials in its ranks.

Its presidential candidate, 88-year-old Beji Caid Essebsi, served as interior minister under Tunisia's first president, Habib Bourguiba, and was later speaker of parliament under Mr Ben Ali.

He is considered a frontrunner in the presidential election.

Nidaa Tounes does not have the seats to govern alone but its supporters hope the party wins the presidency

Nidaa Tounes rejects the notion that it represents a return of the old regime.

"The revolution is our duty and a source of inspiration," says executive committee member Mahmoud Ben Romdhane, arguing that the RCD was "the state party, with 2.5 million members".

Nidaa Tounes won the election but does not have enough seats to govern alone.

The shape of a future government remains unclear. A national unity government that includes Ennahda has been mooted and remains a possibility. But it would be unlikely to go down well at grassroots level.

"We will have to make hard decisions, the answer is not easy," says Mr Ben Romdhane.

His party has a good chance of making it into the presidential run-off expected in late December, and wants to start coalition talks after the result of the presidential election is known.

For Nicole Rowsell, programme director of the National Democratic Institute, the Tunisian commitment to inclusion is at the heart of its successful transition.

"There have been a number of moments when debate came to an impasse or the process stalled entirely," she says.

"But politicians reached out and recommitted - in the end it was hard-nosed political compromise that has brought Tunisia to this milestone."

Despite all the political progress and praise, many Tunisians remain unconvinced that the revolution they started has delivered real change.

In the parliamentary election, voter turnout in Sidi Bouzid - the birthplace of the revolution - was the lowest in the country.

Even in the capital, Tunis, many poorer Tunisians are despondent.

On Rue Charles de Gaulle, 30-year-old Mahres is one of hundreds of illegal street vendors in the area, selling everything from socks to cooking pots.

This informal economy is a huge problem for the Tunisian state finances, but for many people, selling goods illegally is the only way to make ends meet.

Mahres, who has a wife and young daughter, says: "I want somewhere where I can work - a space to sell my goods.

"I have been asking for permission for a while. Instead we always have problems with the police. The state has never delivered for us - so why should I vote?"

Empty coffers

Whatever the make-up of the next government, demands for greater economic opportunity are unlikely to disappear.

Those demands - one of the root causes of the revolution - have not been addressed. And neither has reform reached the security services or justice system.

People are unhappy about the arbitrariness of the system, says economist Mohamed Ali Marouani

A survey conducted by the Pew Research Center has suggested waning confidence, with just 48% of Tunisians saying democracy is preferable to other kinds of government.

Pew said part of the discontent may be explained by economics - 88% of respondents said the country's economic situation was bad.

"People are really unhappy about the arbitrariness of the system," says Mohamed Ali Marouani, an economist who teaches at the Sorbonne and has done consultancy work for the Tunisian government. "The Ben Ali family left, but the system never changed.

"If you are linked to the political system you have access to finance and licences."

So far this year, foreign investment has fallen by 25%, the public coffers have emptied and youth unemployment remains stubbornly high.

Election observer Mr Smaali sympathises with the despondent view but says now is the time to demand change.

"People have the opportunity to decide for themselves - in the past dictatorship decided for us," he says.

"We need to leave that mindset of dictatorship behind and remain involved and engaged. We need to keep looking forward."

- Published9 October 2024

- Published12 November 2014

- Published30 October 2014

- Published1 October 2014