World still learning from Ethiopia famine

- Published

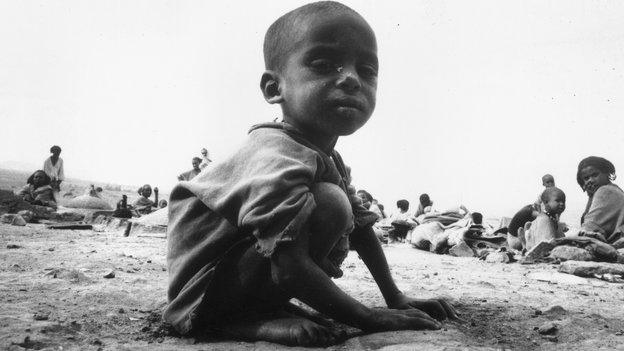

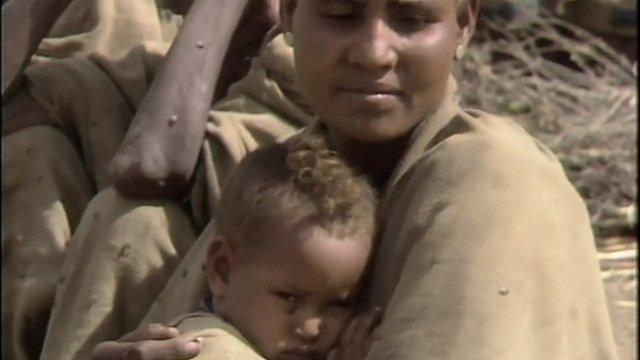

Many thousands suffered from malnutrition in 1984

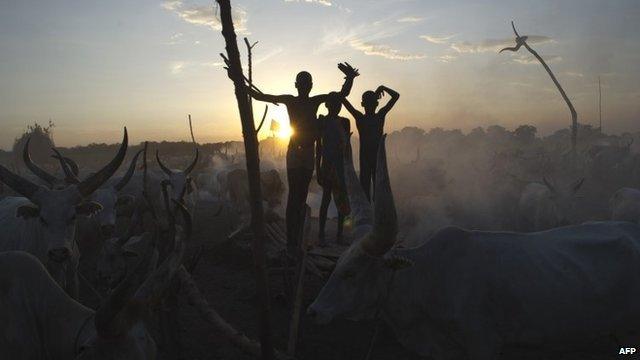

Today the world is seeing one humanitarian crisis alongside another - in Syria, Central African Republic, South Sudan and the countries affected by the Ebola virus. Together they place huge, competing demands on humanitarian organisations.

Thirty years ago, at the end of November 1984, there was one disaster above all galvanising the world's attention - the famine in Ethiopia, which was eventually to kill up to a million people.

At that time, donors were racing to get relief supplies to the worst-hit northern areas of the country in an aid operation on an unprecedented scale.

But, as often happens, it was a desperate effort to catch up with the need.

I journeyed up the spine of Ethiopia, northwards from Addis Ababa, while covering the 1984 famine. My overwhelming memory is of parched countryside, bare hills - and weary and weakened men, women and children congregated in places they thought they might find food.

I was part of the BBC team that, late in the October, finally managed to get access to the epicentre of the famine.

Thousands were dying every week, the impact of drought compounded by the Marxist regime being in denial about the famine's severity and by the region being caught up in civil war.

An aid official described it as "Hell on Earth". It didn't seem an exaggeration.

Although within weeks planes from Western air forces were dropping pallets of food, with aircraft from Eastern bloc nations involved in the aid operation too, and fleets of laden food trucks were reaching the main relief centres, it still took an agonisingly long time for the death rates to come down in some places.

Changes and challenges

Today that same northward journey is a barometer of both the changes that have taken place and the challenges that remain.

Markets are buys and bustling now

In 1984 mothers in worn embroidered calico dresses, clutching emaciated children, would run out into the road and risk their lives trying to stop vehicles and sell whatever possessions they still had.

Now you pass through bustling towns and villages, three-wheeler taxis plying their trade everywhere and people moving animals to and from market.

You see a good deal of construction under way, and new universities in the larger towns.

There is more irrigation, and this year up in these highlands the food crops look good.

As spectacular as the scenery is - with mountain ridges and gorges folding into one another and ever changing light - it is also a reminder of the hard work for many of making a living here. And Ethiopia now has 90 million people - twice as many as at the time of the famine.

We reach Korem, where in 1984 we had seen so many succumb to hunger and sickness on the barren plain on the edge of the town.

Today there is a small hotel there, a college, houses.

But those tragic images come flooding back.

On this trip I met a local administrator who had been a rebel fighter in the area in 1984.

The famine had been heartbreaking, he said.

And lessons had been learnt - now they were trying to protect the natural resources, to introduce more commercial farming and industry.

Rapid action needed

Another brutally obvious lesson of the 1984 Ethiopian famine was the need for humanitarian operations to be "scaled up" rapidly when the distress of a population became evident.

Politics and conflict were a large part of problem in Ethiopia but not the whole story.

Much more recently famine struck Somalia in 2011, and there was acknowledgment afterwards that thousands had died before aid geared up - again conflict was a severe constraint.

But now with Ebola too, more searching questions are being asked about the capacity and the flexibility of the response to the world's many pressing humanitarian needs.

It was Ethiopia's disaster that in many ways helped to shape the global humanitarian system we have today.

- Published23 October 2014

- Published19 May 2014