Ebola crisis: Returning to Kigbal village in Sierra Leone

- Published

Andrew Harding revisits the town of Kigbal to see what's changed for its Ebola orphans

One month ago, Kigbal village, about three hours' drive from Sierra Leone's capital, was in the most agonising distress - ravaged by the Ebola virus, and seemingly ignored by the outside world.

The dead and dying lay on one side of the main road. Dozens of children - many told us they had lost one or both parents to Ebola - stood in an abject cluster on the far side of the tarmac.

A month later, I have come back to see what has changed.

It is an eerie feeling, as we pull up in the car, wondering how many of the people we interviewed in late October will still be alive.

We head straight to the "bad" side of the road, where most of the infections and deaths had occurred.

Health officials had privately blamed a local hospital for discharging a man with suspected malaria, who came home with what proved to be raging Ebola.

In October, we had tried to speak to two women and a two-year-old child - all suspected Ebola cases - who had been lying under a tree in the dirt in obvious distress. The mother and child had long since died, we were told.

Then I spot a familiar face.

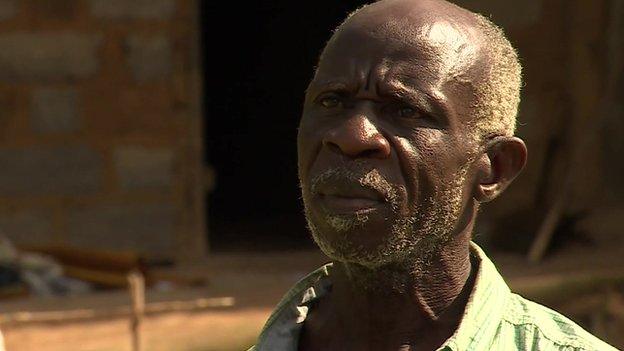

When Andrew first met Momo Sese, he pleaded the team for help for his wife who was suffering from Ebola

Mr Sese was unable to touch his wife (pictured) who had to stay on the other side of the road from him

Momo Sese is grinning broadly as he beckons me over to his porch.

A month ago, he had begged for advice about how to help his wife, Fatu, who was weak with fever. He said he was "scared" of her.

"Welcome," says Fatu, who is sitting on the same bench as before, but now in evidently robust health. "I was so sick. I am surprised to be alive. They took us to hospital, and gave me medicine, and even an injection," she says.

"I didn't touch her. I chose not to," says Mr Sese, explaining that officials had come soon after our visit. "That's what saved us all," he says.

Now Momo and Fatu are reunited following her recovery from Ebola, one month on

I ask if he now feels safe to touch Fatu, and there are polite smiles and some brief confusion as he thinks I'm implying a more intimate act. Then he grins, laughs, leans over and gives his wife a big hug.

Changed man

A month ago the local paramount chief Alimamy Baymaro Lamina II showed us around Kigbal and spoke with deep anger about what he said was the utter lack of attention shown by Sierra Leonean and international humanitarian workers to the crisis here.

"I've been calling and calling and not getting any help. My people are dying," he told me.

Meeting him again in the village this time, the chief appears to be a changed man.

Mabinti Kamara, who Andrew Harding met on his last trip to Kigbal, has now lost both her parents to Ebola

"Now we are getting very big help. From the government. From the Europeans. When they got the message from the media, that's when we got help. I'm very happy now," he says, declaring that "we are totally having control" over Ebola.

That may be overstating the case - and a diplomatic nod towards his criticism-sensitive political bosses in Freetown - but Chief Lamina shows us a new Ebola treatment centre being opened a few miles up the road and insists that Kigbal itself is now "Ebola-free", at least for now.

Still, the outbreak has had a devastating impact on an already impoverished community. Sixteen children died, the chief tells us. A village of 300 has lost one-sixth of its population.

"He dohn die (he has died)," says Mabinti Kamara, 15, before bursting into tears and rushing away.

When we last spoke, she had just lost her mother, but had no news about her father who had been taken away a few days earlier. She is now living with an uncle.

'Vulnerable orphans'

We ask about another child - six-year-old Alusin. He and six other young children had been separated from the others in October because they were considered most at risk.

Alusin (in green) seemed unlikely to make a recovery from the virus last month, but is found alive and well

We had found them sitting in a makeshift "isolation" area, beside two adults who appeared to be dying of the virus. Alusin had told us "my head hurts". Survival seemed, frankly, unlikely.

But an hour or so later, we track down Alusin and all but one of the other children (a baby boy died), living on the outskirts of the nearby town, Port Loko.

"We will take as many [orphans] as we can, but they reckon there are 7,000 or so [nationally]," says Miriam Mason-Sesay, smiling as the children cluster around her. She runs a small British educational charity, Educaid, which operates in several towns in Sierra Leone.

Ms Mason-Sesay helped to rescue Alusin and the others about 10 days ago, moments before they were going to be taken - and almost certainly put at even greater risk of infection - in a larger Ebola treatment centre.

Sierra Leone's president said this week the country only than one-third of beds required for the Ebola crisis

The Ebola crisis has claimed more than 6,000 lives during the current epidemic in parts of West Africa

"For some they will find okay solutions within their communities. [But] our experience is that a lot of those can be very vulnerable and that's the concern really that we don't end up with lots and lots of those children again," she says, referring to the aftermath of Sierra Leone's devastating civil war, more than a decade ago.

In the new home being built on a green hillside for the children - and as many others as they can handle - Alusin and the others listen to music on a radio and try a few dance steps.

Alusin's mother, Zeinab, has been hired by Educaid to care for the children. She is in her early twenties. She had the virus, but survived. Her husband and small baby did not.

Zeinab grins broadly as she puts on a small puppet show for the children, but when I ask her about what will happen next, she goes quiet, and then outlines the poverty and uncertainty that still hover over the lives of so many broken families in places like Kigbal.

"I never went to school. I'm very young. I was married off to a husband who is now dead. I can't say anything about the future. I am resigned to whatever happens. I am prepared to do anything," she says.

Read Andrew Harding's other reports from Sierra Leone: