Tanzania's albino community: 'Killed like animals'

- Published

"We're being killed like animals" - An albino woman in Tanzania where over 70 albino people have been murdered in the last 3 years

People with albinism face prejudice and death in Tanzania. A new campaign is now being launched to end hostility towards the tiny community of about 30,000. BBC Africa's Salim Kikeke met some of them.

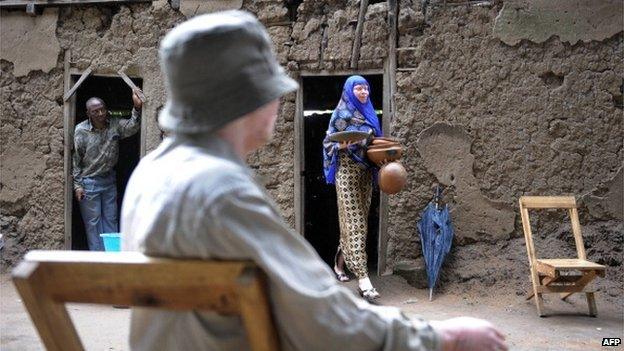

Mtobi Namigambo, a fisherman by trade, sits calmly on a stool outside his mud house in Ukerewe island.

Once a sanctuary for albinos, this is no longer the case. His four-year-old son, May Mosi, who has albinism, sits on his lap. Showing off his newly learnt skills, May counts from one to 10, confidently.

Mr Namigambo occasionally throws a glance at his wife, Sabina, who is seated on a mat at his feet preparing the family's evening meal. Their other two children are playing nearby. They also have a newborn baby, sleeping inside the house.

When May was three months old, he escaped an attempted kidnap.

"I had gone to the lake to fish. They were all alone in the house when the attackers struck," Mr Namigambo tells me.

"My wife jumped out of the window and ran to safety with May, leaving the two children behind, who were not harmed at all."

'Hacked to death'

"The attackers were after May," Mrs Namigambo chips in, "My husband was away on a fishing trip and they knew about it. That's why they came for my boys.

"After jumping out of the window, they still came after me and I was screaming for help. They only backed off when I woke up the neighbours."

People with albinism risk being killed for their body parts

Activist Alfred Kapole hopes that the next generation will have a safer future

Albino people, who lack pigment in their skin and appear pale, are killed because potions made from their body parts are believed to bring good luck and wealth.

More than 70 albinos have been killed over the last three years in Tanzania, while there have been only 10 convictions for murder, campaigners say.

In the most recent case, in May, a woman was hacked to death.

"We're being killed like animals. Please pray for us," one albino woman sings, at an event called to promote the rights of albinos.

'Targeted for hair'

May is among 70 people with albinism who live in the remote island of Ukerewe, which is three hours away from Mwanza, the second largest city in Tanzania.

"We would urge the government to do more in educating the community here," Mr Namigambo tells me.

"The government once held seminars about albinism. It made a lot of difference, but not any more," he adds.

Mashaka Benedict stands by a statue which promotes the rights of albino people in Sengerema town

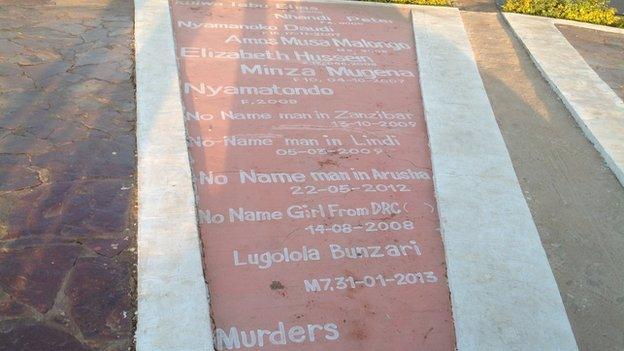

Albino people who have been killed, some of them from neighbouring states, are remembered

Campaign group Under the Same Sun, which works closely with the local albino community, says the island is not as safe as people would like to believe.

The chairman of the regional Tanzania Albinism Society, Alfred Kapole, an Ukerewe native, was forced to flee to Mwanza city.

"He was among the first person with albinism whose case reached the courts after a village leader attempted to kill him for his hair," says Vicky Ntetema, head of Under the Same Sun.

"Last year his home was attacked. Luckily he was in Mwanza. There was another attempt on his life this year."

Ms Ntetema says this is a common experience for albino people.

"A family of a young girl with albinism had to flee their home twice, in 2011 and 2012, when unidentified men attacked them, saying that they were sent by the father of the home, a fisherman, to get the girls' hair.

"When people commit crimes they go by canoes to neighbouring islands where they cannot be found," she adds.

'Bodies stolen'

The Tanzania government has launched a campaign to raise funds to help persuade communities to abandon old beliefs and stop targeting albino people.

However, the campaign focuses on urban areas, not in rural areas where albinos face the biggest threat.

"We don't have the capability, or means to reach communities at village level. We mainly rely on radio or television, but we can't reach the grassroots because of costs," says Ramadhani Khalfan, chairman of the Ukerewe Albino Society.

About 70 peole with albinism live in the remote island of Ukerewe,

Albino people face the biggest threat in rural areas

In Sengerema, some 60 km (34 miles) from Mwanza, a monument has been erected at a roundabout in the middle of the town.

It is a life-size metal statue, depicting a pigmented father holding his child with albinism on his shoulders while a pigmented mother puts a wide-brimmed hat on the child's head to protect him from the sun.

There are also 139 names of victims who were killed, attacked, or whose bodies were stolen from graves.

A representative of the Sengerema Albino Society, Mashaka Benedict, told the BBC that even educated people still believe that albino body parts can bring wealth.

"If that's the case, why are we not rich?" he asks.

Mr Benedict alleges that prominent people are involved in the "killing business" and this is why very few people have been arrested, charged, convicted or jailed.

"How can a poor man offer $10,000 [£6,300] for a body part? It's the businessmen and politicians who are involved."

The police say they try their best to investigate attacks.

"These cases are complicated because most incidents happen in very remote areas where there is no electricity, for example, and that makes identifying perpetrators at night very hard," says Mwanza police commander Valentino Mlowola.

"We investigate each and every case and claim, but as you can see, it's not simple."

Despite the failure to solve cases, many people living with albinism are hopeful that public attitudes will change and children like May will be able to have a life, free of persecution and violence.

- Published27 October 2010