Boko Haram: Can regional force beat Nigeria's militant Islamists?

- Published

Nigerian soldiers have failed to end Boko Haram's six-year insurgency

At last, Nigeria and its neighbours - Chad, Niger, Cameroon and Benin - have a plan for their Multi-National Joint Task Force (MNJTF) to fight Boko Haram's Islamist militants.

The plan has now been approved by the African Union.

But what are the chances that this 8,700-strong regional force will root out an insurgency responsible for the death of tens of thousands in recent years?

The area that the MNJTF will be covering draws the force's first limit.

Military and diplomatic sources have confirmed that MNJTF soldiers will only operate between the outskirts of Niger's Diffa border town, and the towns of Baga and Ngala in Nigeria.

In other words, the regional force's main task will be to secure the Nigerian side of Lake Chad, which represents "only 10 to 15% of the entire area where Boko Haram operates", according to a diplomat based in the region, who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

"This plan won't solve the problem, it will remain up to Nigeria to do most of the job," the source added.

As a matter of fact, Nigeria remains extremely reluctant to have an international force on its territory.

Africa's giant would rather show that it can lead regional operations or at least be part of them - Chad in the 1980s, Sierra Leone and Liberia in the 1990s; Darfur later - than host foreign armies to solve trouble at home.

Nigeria has always remained very protective of its territorial sovereignty since the Biafra war.

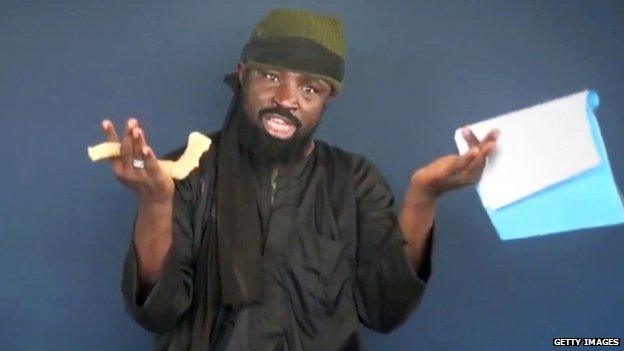

Boko Haram at a glance

Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau has declared an "Islamic State" in northern Nigeria

Founded in 2002

Initially focused on opposing Western education - Boko Haram means "Western education is forbidden" in the Hausa language

Launched military operations in 2009 to create Islamic state

Thousands killed, mostly in north-eastern Nigeria - also attacked police and UN headquarters in capital, Abuja

Some three million people affected

Declared terrorist group by US in 2013

But Nigeria also has a history of border disputes with the neighbours who are now pressing for a regional solution. Whether over islands on Lake Chad that belong to Niger or Chad, or the oil-rich Bakassi peninsula that once led Cameroon and Nigeria to the brink of war.

These tensions went live on Twitter two weeks ago when the spokesperson of Nigeria's army, General Chris Olukolade, furiously responded to comments apparently coming from the defence ministry in Niger suggesting that Nigerian soldiers were running away from Boko Haram fighters.

"Nobody will disrespect my Mother[land], external!" he wrote.

"We don't cross our boundaries. It is unacceptable for any foreign government to say our soldiers run."

In this context of distrust, it is still unclear whether Nigeria will agree to have Niger and Cameroon conduct cross-border operations, as Chad has already been doing.

Zones of deployment will have to be assigned once the plan agreed in N'djamena is approved by the African Union (AU).

Nevertheless, diplomats concede that the level of co-operation between military planners last week had been "surprisingly impressive".

Diplomatic sources have told the BBC that Nigeria and Chad will provide most of the troops; respectively 3,250 and 3,000 men, including a Chadian special forces unit.

There will be 950 men from Cameroon, 750 from Niger and the remaining 750 from Benin. All of them will be under the command of a Nigerian general.

These figures include infantry troops and artillery but also gendarmes and police squads as well as engineering, logistical and civilian units.

'End of the food chain'

No timeline has so far been attached to the current plan; what will be achieved on the ground may drive any future decision to review this deployment.

On the map, the Cameroonian border area seems left out of the plan, which may force Chad to keep its current scenario going with some of its troops deployed south of its capital to fight alongside the Cameroonian forces.

As for the United Nations, "it comes a bit at the end of the food chain", a source at the Security Council said.

Western powers - perhaps with the exception of France - do not seem inclined to give this force more than a political endorsement to keep it a regional initiative.

Still, Nigeria is "dragging its feet at the Security Council", as another diplomatic source at the UN put it.

"Nigeria remains passive on the issue and it makes sure that things don't move forward when it should be the pen-holder [submitting statements and texts]."

President Jonathan is hoping success against Boko Haram will help his re-election campaign

It is election time in Nigeria and there is a sense that mounting a plan against Boko Haram now puts the incumbent President, Goodluck Jonathan, in an uncomfortable position.

After six years of escalating violence in Nigeria's north-eastern states, the Nigerian authorities have postponed the general election to allow time for a last-minute offensive against the insurgents.

But although Nigerian troops have recaptured a number of towns from Boko Haram's hands - at times with Chadian help - over the past two weeks, there is little chance that the insurgency can be crushed before the end of the month, when the election is now due.

Mr Jonathan, who is seen as having barely dealt with the crisis, is now squeezed between his electoral campaign and a military offensive, hoping that both will turn in his favour.

In the meantime, Chad has clearly taken the lead. At the UN Security Council, where it is said to be "pushy", and on the ground, with Chadian troops deployed in Nigeria but also in Cameroon and in Niger.

Chad has been impatient to act in order to protect its supply routes, crucial to its economy. Goods come through Cameroon's Far North while it exports oil through a pipeline running through Nigeria's Adamawa state.

There is scepticism that Nigeria will even bring a resolution before the Security Council following the AU vote, in which case Chad would probably seek UN backing for the region.

Boko Haram regional growth?

Funds for the MNJTF will not directly come from the United Nations but from donor countries led by France, the US and the UK, which will all stress human rights issues, given the track records of the armies involved.

In a paper published last month, external, Marc-Antoine Perouse de Montclos, researcher at Chatham House, suggested that a multi-national response to Boko Haram's threat might just help the Nigerian Islamist insurgency take on a more regional dimension.

After all, Boko Haram launched its first attacks on Chad and Niger after the authorities of both countries said that they were joining the fight.

On the contrary but with tempered optimism, Western diplomats reckon that this current plan will at best stop a Boko Haram spill-over in the region and weaken the insurgency in Nigeria.

Boko Haram means "Western education is forbidden" in Hausa

But it will not be enough to flush it out of the north-eastern states.

"Nigeria isn't really part of the game so far, but Abuja is obviously key to solving the crisis," wrote Mr Perouse de Montclos.

Diplomats agree. The MNJTF may well get the institutional framework it will need to operate, but the co-operation efforts made by Nigeria's francophone neighbours will not achieve much without a real Nigerian strategy - both military and political - against Boko Haram.

A source at the UN Security Council bluntly summed it up: "All we see is the failure coming from six years of non-action.

"Nigeria needs to get a lot more involved."