US-led exercise in Chad prepares troops to fight terror

- Published

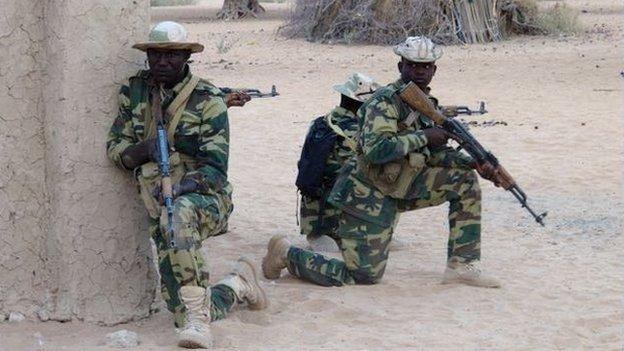

Soldiers take part in Operation Flintlock in the Sahel region of Chad

Troops from 20 African countries are training to fight terror in an exercise deep in the desert of Chad. The drills are part of new Western counter-terrorism tactics on the continent.

Down at the firing range, it is the Chadians' turn. American special forces are training them on the machine gun.

Chadian soldiers queue to lie down on a piece of cardboard, load the weapon and aim at a target around 150 metres away.

Occasionally we hear the "ding" from a bullet hitting the metallic target.

But what makes the soldiers cheer is when one of their comrades holds the trigger down, shooting several rounds at once from the automatic weapon.

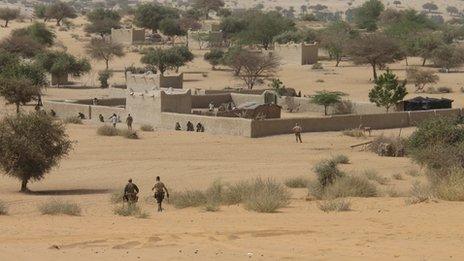

This shooting session is taking place in western Chad, in a section of the Sahel region that skirts the southern edges of the Sahara Desert.

It is part of Operation Flintlock, an annual counter-terrorism exercise led by the United States and held with their Nato allies in West Africa.

This tenth edition is particularly timely. These drills are taking place against the backdrop of a region preparing to take on Boko Haram in Nigeria.

In fact, these Chadian troops may be going straight back into battle as soon as their training is over.

The exercises are taking place in Mao, on the edge of the Sahara

Chad has taken the lead in the fight against Boko Haram, having already engaged the group in neighbouring Nigeria as well as in Cameroon and Niger.

"Our biggest challenge is intelligence to allow us to fight," explains Gen Zakaria Ngobongue.

"Our means may be limited - we have to make do with our weaknesses - but if our Western partners are supporting us and accompanying us, I am sure that we will put an end to Boko Haram."

Boko Haram at a glance

Founded in 2002

Official Arabic name, Jama'atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda'awati wal-Jihad, means "People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet's Teachings and Jihad"

Initially focused on opposing Western education

Launched military operations in 2009 to create Islamic state

Designated a terrorist group by US in 2013

Declared a caliphate in areas it controls in 2014

Light footprint

Providing intelligence is something that Western powers are ready to do - and are already doing.

Unlike in Iraq, where they are carrying out air strikes against Islamic State (IS), the US and European countries would rather stay behind the scenes of this conflict and other counter-terrorism operations in the Sahel region.

British forces have been training Nigerian units over the last few years, and are doing so here during Flintlock.

"We're in a phase now of persistent engagement and a regular rhythm of involvement with our partners, but keeping our footprint light, rather than just an episodic burst and then just go away again," says Tom Copinger-Symes, a British Brigadier.

A light footprint, he says, can mean "everything from low-level training, tactics, to co-ordination, to intelligence fusion and really how to work together within a coalition".

Chad's army is seen as one of the strongest in the region

A new approach

Engaging as a coalition is what units from African nations will need. They have been doing it as a live exercise here; soon, they will have to do it for real.

Mounting a regional force against Boko Haram - the Multi-National Joint Task Force - has so far proven that communication between neighbours remains difficult.

The fight against terrorism has come to the Sahara, but not with the type of military campaign that has been seen in Iraq and Afghanistan.

This year's training exercises in Chad are particularly timely as the region prepares to take on Boko Haram Islamists in Nigeria

The French have redeployed their military forces, mostly targeting al-Qaeda affiliates and establishing a regional presence of undetermined length.

But France, the US and their Western allies have had a different approach to that in Middle East countries - relying on surveillance, very few boots on the ground and the training of regional armies.

Yet, the impact that this build-up of military assets will have on the stability of the region remains questionable.

The US and UK have avoided a combat role in West Africa

A Chadian captain briefs his unit ahead of the live exercise

Analysts point to the nature of relationships that Western states are forging in the Sahel with authoritarian regimes in the name of counter-terrorism, and warn that they could lead to further trouble in fragile states there.

As one European senior military official, who didn't want to be named, tells me: "What is the alternative?"

Islamist militancy now spans from Nigeria to Mali in West Africa, to Libya further north, where IS fighters have become further entrenched in recent months.

Major General James Linder, Commander of US Special Operations Command Africa, says: "All of us are concerned about the instability in Libya and how that spreads across the region - whether it's the movement of foreign fighters or whether it's the movement of weapons systems, that put many different nations at risk."

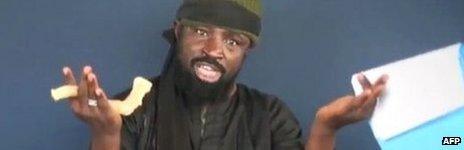

Boko Haram means "Western education is forbidden" in Hausa

'Can't do it alone'

Over the weekend, the leader of Boko Haram pledged allegiance to IS - a move that was expected and that, at least for now, may not change the Nigerian group's capacity.

But it certainly raises fears that networks of jihadi groups are expanding across the region.

"We can't fight these enemies alone," says Maj Gen Linder.

"One man can't do it alone, one nation can't do it alone. We have to work together."

Some Chadian soldiers may be sent to fight Boko Haram as soon as their training is over

Western countries are treading with a light step in the Sahara and are hoping that their hosts will do the heavy lifting.

As the light starts going down, a group of Mauritanian soldiers and their Spanish instructors improvise some dance moves in the sand. They clap and chant too.

But all there is to celebrate, for now, is the end of yet another exercise in the desert.