Who wants what in Libya?

- Published

Islamic State (IS) militants are said to have kidnapped nine foreign oil workers in a raid in Libya.

It follows the beheading of 21 Egyptian Coptic Christians in February.

The internationally-recognised government is trying to run the country from the east, with its parliament based in the city of Tobruk.

In Tripoli, another body claims to be the legitimate government. But is the real power struggle between the militias associated with each group?

The BBC World Service's The Inquiry investigates the forces operating in Libya.

Mattia Toaldo: Tobruk parliament paralysed

Mattia Toaldo follows events in Libya for the European Council on Foreign Relations.

"The elections were held on 25 June last year. [There was] not a very high turnout because of the violence which had already started but still, it's the parliament in Libya."

Mattia Toaldo argues the parliament in Tobruk is fatally compromised by its distance from Tripoli

It includes many who worked for the state under Colonel Gaddafi, although Mattia Toaldo argues that doesn't mean they supported him:

"It would be unrealistic to think that someone living in Libya - a country where 80% of the workforce works for the government - did not work for the government for 42 years."

But he says history is not the main threat to the parliament's legitimacy; geography is.

"The problem with the government in Tobruk is that it's just the steering wheel but the car is 800-1000 km away."

The car is in Tripoli - home to the civil service, the central bank, and the organisation controlling oil production - but the Tobruk parliament can't steer it because the capital is in the hands of its rivals, who say they are the legitimate government.

"In terms of people's perception of who is the government, this is very blurred at the moment. In terms of who provides the daily services... in most cases it's the municipality, the local council.

"Laws are passed in Tobruk. But, yes, any law that implies a civil service structure to be implemented cannot be implemented by the Tobruk government."

The question is whether it's the government and parliament who wield the real power; or whether that lies in the hands of a military man, General Khalifa Haftar. Once a Gadaffi loyalist, Haftar later fell out with the dictator.

"He is considered to be quite a divisive figure even within the Tobruk camp.

"Not everyone likes him but he's been recently appointed as head of the armed forces and his first goal is to fight terrorists, and he thinks he's fighting terrorists also on behalf of the West."

Many suspect he has political ambitions of his own:

"Haftar was accused of organising a coup d'etat on Valentines Day in 2014, except there is no real Libyan army to do a coup d'etat and there is no real state to control. So it's a coup d'etat without the 'etat'."

So who calls the shots in Tobruk?

"At the moment those who hold weapons hold more power, so people like Haftar.

"Basically since the overthrow of Gaddafi in 2011, Libya has never really experienced a period of peace. It was not that militias were integrated into the state, it was the state which has been integrated into the militias."

Abdul Rahman Al-Ageli: Fear of military dictatorship

Abdul Rahman Al-Ageli was born in Libya but moved to the UK as a child.

Abdul Rahman Al-Ageli

He returned to fight against Gaddafi in 2011, and ended up working for the prime minister until 2014 when he left, frustrated by the tension between rival groups:

"There is an Islamist versus non-Islamist agenda. You have the IS issue, the al-Qaeda issue, the Muslim brotherhood issue, you have moderate Islamists, hardliners, you have a revolutionary versus counter-revolutionary narrative.

"And you have also a very interesting social dynamic which is non-Bedouin Arab versus Bedouin Arab."

In the first election post-Gaddafi, an Islamist party did well. Its main agenda was to exclude anyone who had worked for the Gaddafi regime.

But it soon lost support, and was heavily defeated in the House of Representatives elections.

Those voted out disputed the legitimacy of the results, and refused to step aside.

So there are now two bodies claiming to be the government; one in Tripoli, the other in the east. "Each side fears that their opponent will exclude them if they were to take power."

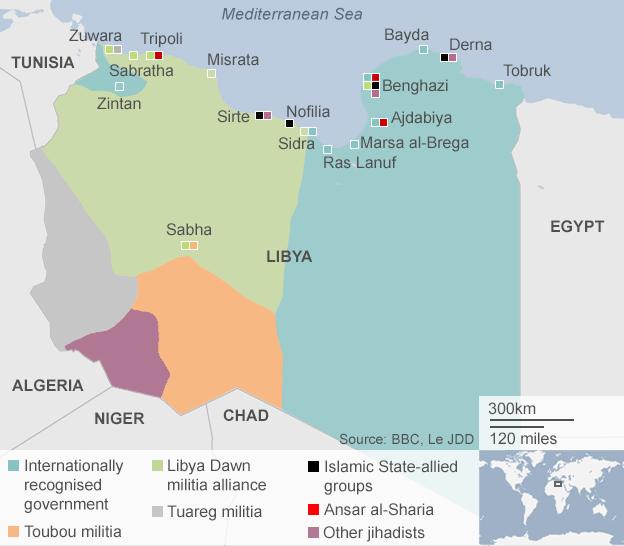

Libya's rival power bases

Military support for the Tripoli government comes from Libya Dawn:

"It can be described as a loosely organised and fragmented amalgamation of several revolutionary brigades, mainly from the town of Misrata, in a fragile alliance of convenience with certain Islamist factions, united against General Haftar's Operation Dignity in the east."

Abdul Rahman Al-Ageli says all the players in Tripoli fear General Haftar:

"They fear an Egypt-type situation. They fear a military dictatorship."

Journalist Mary Fitzgerald: IS exploiting Libya to taunt Europe

Mary Fitzgerald has reported on Libya since the Arab Spring and spent last year in Tripoli. She says Islamic State's involvement was inevitable.

Journalist Mary Fitzgerald believes Islamic State is well placed to exploit Libya's fragile state

"Since late 2011, hundreds of young Libyans have gone to join anti-regime forces in Syria and many of those young Libyans ended up with Islamic State.

"Last year, a number of the Libyans who had gone to Syria and Iraq and joined Islamic State there started returning home, and around the same time Islamic State sent some key ideologues and planners to Libya to assess Libya's potential."

Libya is an appealing target:

"You're talking about a country with porous borders, vast ungoverned spaces and right now a political and security vacuum.

"All of these factors make it very conducive indeed to Islamic State expansion to Libya."

IS claims to control three provinces in Libya, though Mary Fitzgerald thinks they are exaggerating, in order both to attract foreign fighters, and to entice local men away from other militant groups.

These include Ansar al-Sharia, one of Libya's best known extremist organisations which was listed as a terrorist group after the US ambassador to Libya was killed.

"This is a large part of the radical landscape in Libya, this issue of what you could call brand rivalry."

Mary Fitzgerald describes a youth subculture rooted in radicalism, which IS exploits through social media and gruesome videos, like that showing the Egyptian Christians' murder:

"What was quite striking were the references to Rome in that video. With the killings of the Egyptians, they were obviously targeting Cairo, but they were also taunting Europe.

"Remember that Libya is about 200 miles from Malta, an EU member state."

Issandr El Amrani: International players divided

Issandr El Amrani is North Africa Project Director at the conflict prevention organisation International Crisis Group.

Egypt backs the internationally-recognised parliament in Tobruk, as does the United Arab Emirates. Both fear the spread of Islamism.

Issandr El Amrani argues western countries need the UN-sponsored negotiations to succeed

"At its height over 1.5 million Egyptians worked and lived in Libya. If you go to some Libyan cities most of the bakers, for instance, are Egyptian and so both countries are affected.

"Egypt currently supports the side of the Libyan government that is anti-Islamist. It projects onto Libya this Islamist versus secular divide that it sees in itself, but that's not the Libyan reality."

On the other side are countries like Qatar and Turkey, who in 2011 had backed political Islam as the next major political force across the region.

"They've certainly lost their bets in Egypt with the downfall of the Muslim Brotherhood, and I think they're very afraid of losing the major advance that they have made in Libya where the former parliament was not dominated but certainly very influenced by political Islamists."

Issandr El Amrani says most countries haven't taken sides, hoping United Nations peace talks will deliver a unity government. Several countries, he says, have a direct stake in what happens next:

"France supports the negotiations process, but is very concerned, not about what's happening where most of the fighting is taking place in the north, but in the south, because in southern Libya you have all sorts of groups coming in from Mali and Niger.

"So they're trying to make sure that these groups don't eventually return to northern Mali and then undo the work that the French have done there.

"Italy imports over 25% of its natural gas from western Libya so it wants energy security.

"If you look at the US, its dominant policy in the Middle East is about fighting Islamic State.

He says western countries now urgently need the UN-sponsored negotiations to work:

"The alternative is really prolonged conflict and it would be much, much more costly than working out a political deal now."

The Inquiry is broadcast on the BBC World Service on Tuesdays from 13:05 GMT. Listen online or download the podcast.