The hunters breaking an Ebola ban on bushmeat

- Published

Scientists believe bushmeat is the origin of the current Ebola outbreak. A year ago, Sierra Leone put a ban on bushmeat - but is it working?

The old man crouched in the undergrowth and started mewling.

The sound was a cry of distress.

But the old man was not in pain.

He was imitating the sound of a baby antelope calling to its mother.

Then the veteran hunter pointed a stick, posing as a rifle, in the direction he was sending his distress call.

He turned to me and said quietly:

"My copy of a baby antelope voice will bring the mother antelope towards us".

Then he said, in a gentle voice:

"When she comes near to me, I will kill her".

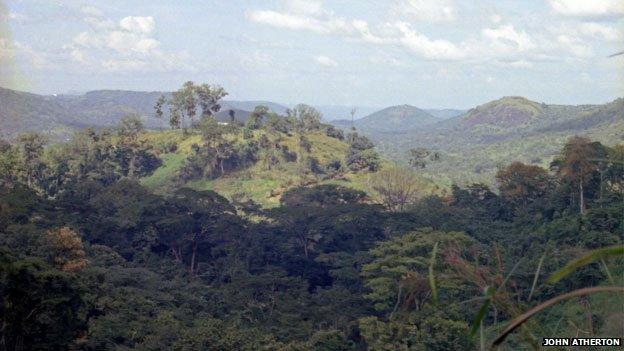

I was two hours drive outside the northern Sierra Leonean town of Kabala, in the ruggedly beautiful Wara Wara mountain range.

I'd linked up with a group of traditional hunters who were demonstrating how the Ebola-inspired ban on bushmeat hunting in Sierra Leone isn't working.

The ban came into force last year.

The Wara Wara mountains

Scientists have warned that bushmeat - non-domesticated forest animals hunted for human consumption - is probably the natural reservoir of the Ebola virus.

Every now and then, the scientists say, the virus jumps from animals to humans. The jump is probably via human contact with fresh bushmeat blood.

"I do believe there's a scientific basis for believing the Ebola virus resides in bushmeat," said Bala Amarasakaran, a Sierra Leone-based expert on forest primates and conservation.

"That's why the government introduced the ban on bushmeat trading, and I support it."

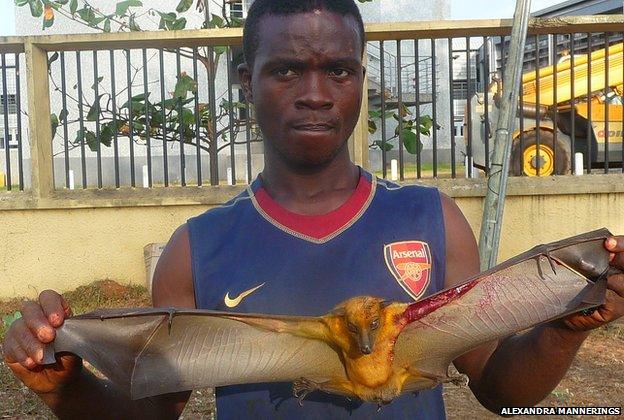

Bats are known carriers of the Ebola virus - this hunter was pictured last year

The Minister for Agriculture, Joseph Sam Sesay, confirmed to me that the ban was still in place and said it was broadly working.

But in the Wara Wara mountain range, the bushmeat hunters I met were obviously active.

Sierra Leoneans can have a disarming tendency to be honest and dishonest at the same time.

They appear to lie about some controversial topic. But they also smile knowingly at you as they talk. And then they find a way of telling you the truth anyway.

One of the hunters I met told me very clearly that he didn't seek out bushmeat any more because the government had banned the trade.

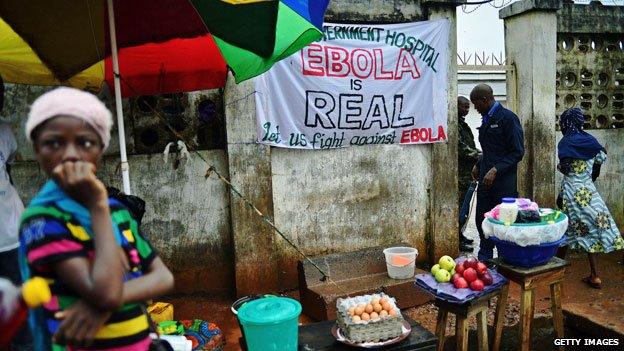

Outside an Ebola clinic in Sierra Leone

But I teased out the truth by promising not to reveal his name, or the location we were in.

So he then proceeded to show me freshly laid traps in the forest and several large joints of freshly killed antelope and wild "bush goat" meat.

Traditional hunters are an elite group in Sierra Leonean rural society.

True to the form of all hunting and fighting men, they are full of impressive stories.

They boast of how large the buffalo they once killed was.

They explain how they have supernatural powers; they can appear or disappear at will in the forest.

In short, they say how tough and powerful they are.

These are not just tall tales.

The traditional hunters of Sierra Leone are indeed highly skilled and resourceful men.

The group I was with showed me five different types of trap.

Some were for taking chimpanzees (babu in the Sierra Leonean lingua franca Krio); some were for killing larger animals such as buffalo, deer or wild "bush cows".

The hunters demonstrate how to set a trap

All the traps were complex arrangements of springing boughs of wood and a killer coil of wire that snared the animal by the foot or neck.

One trap was an enticing doorway of bamboo designed to lure an unfortunate animal in.

A hunter crawled through the small doorway to demonstrate the process for me.

He feigned garrotting himself with the waiting wire.

The hunter then sprawled on the ground, screaming like an animal would do as it tried in vain to escape.

It was, I suppose, a grim display.

But we all had to laugh out loud when the man-animal dramatically "died" and flopped into the undergrowth.

The hunters said they were showing me the traps as a "demonstration".

But I realised this was all part of the playfully honest/dishonest Sierra Leonean show.

It was quite obvious to me that the forest path we had walked along to reach the traps was a well-trodden one.

The hunters were clearly here regularly.

There were freshly-cut tree stumps. And the men with me carefully re-set the "demonstration" traps as we left. They evidently saw no point in wasting a journey to the trap zone - even if it was with a visiting journalist.

The truth is that rural people in Sierra Leone rely on bushmeat for protein.

It is also a delicacy.

The culinary difference between bushmeat and farmed animals in Sierra Leone is like the difference in Europe between expensive, organic sirloin steak and tasteless frozen battery chicken.

My hunch - reading between the honest/dishonest lines - is that the hunters mounted their "demonstration" (that was in fact reality) because they were profoundly proud of their traditions and wanted to impress me.

They succeeded.

I admired the skill of these men.

I also admire conservationists like Mr Amarasakaran who are against the bushmeat trade.

But I doubt if traditional hunters are a major cause of Ebola spreading. The hunting group I was with only take an animal or two every day.

The real cause of the spread of Ebola is a dysfunctional health care system and poor organisation by the government.

I came away from the Wara Wara Mountains believing that the bushmeat trade would probably never be stamped out.

And I was left wondering if the government of Sierra Leone is aiming at the correct targets.

A health worker in Sierra Leone

Listen to: Understanding Ebola on Monday 23 March at 1300 GMT on BBC World Service.

For more on the BBC's A Richer World, go to www.bbc.com/richerworld - or join the discussion on Twitter using the hashtag #BBCRicherWorld, external