Tunisia museum attack tests transition

- Published

The president says "we need national reconciliation"

"Degage!" One word says a great deal.

Four years ago, in Tunisia, you heard this forceful command, in French, a lot. It was the rallying cry of "go away" against authoritarian rule during the unprecedented uprising that came to be known as the Arab Spring.

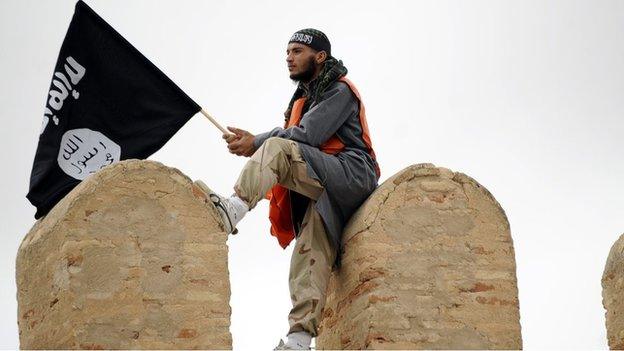

Now you hear that same demand hurled at extreme Islamist groups like Islamic State which have gained a foothold in Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and now neighbouring Libya.

The cry resonates in street protests in Tunis against the attack last week said to have been carried out by gunmen linked to IS. The assault on the country's exquisite Bardo National Museum killed 23 people, most of them foreigners, and inflicted a crippling blow on a vital tourism industry.

Thousands of young Tunisians did "go away" to fight in Iraq and Syria, or to train with radical Islamist groups in neighbouring Libya. But now some who are armed and radicalised are coming home.

"There is no place for Daesh in Tunisia," insists Rached Ghannouchi who, like many in the region, uses an Arabic acronym for IS regarded as a more derogatory term.

Security has been beefed up following the attack

"Tunisia's long-established state and our freedoms will prevent extremists from seizing territory and establishing themselves here," the head of the moderate Islamist party Ennahda, which won Tunisia's first elections in 2011, tells me in an interview in Tunis.

But Mr Ghannouchi flags up a vulnerability.

"If the situation in Libya isn't resolved, Tunisia will remain under attack," admits the 73-year-old leader, who is now personally involved in daunting efforts to bring about a political accord between Libya's two rival governments.

"Young Tunisian men go to train in camps in Libya. They get arms and then sneak back across borders we can't control," he regrets.

Rached Ghannouchi tells the BBC that there is "no place for Daesh in Tunisia"

The two gunmen killed in Wednesday's attack are said to have trained with al-Qaeda in the eastern Libyan cities of Derna and Benghazi and then become part of "sleeper cells" once they returned home.

Tunisian security forces have also been battling al-Qaeda-linked Islamists of the Uqba bin Nafi Brigade in the Chaambi mountains near the Algerian border.

"There is a possibility of other attacks but they are more likely to be of the 'lone wolves' kind we saw in Paris and other cities, not the open war of Iraq and Syria," maintains Tarek Kahlaoui of Rutgers University, who formerly headed Tunisia's Institute of Strategic Studies.

"But we have limited resources and need more training," he tells me when we meet outside the Bardo.

'Soft'

His view is echoed by Sayida Ounissi, a member of parliament with Ennahda.

"At the very moment attackers struck Bardo, we were hearing from army chiefs next door in parliament that they did not have the right resources and training to take on the growing threats," she remarks.

Ennahda has also been criticised by Tunisians with more secular views for being "soft" on Islamists. Mr Ghannouchi flatly denies the accusations.

"On Wednesday afternoon, I had my first cancellation. After I had another one in the evening and another one a day after"

"When we were in government, we classified Ansar al-Sharia as a terrorist group and declared war on them," he insists, referring to another al-Qaeda linked group that operates in Tunisia.

"Secular parties also have no influence in the mosques, so we contained the threat of radical groups there and forced them into hiding," he adds.

It's been a journey of rude awakenings for the prominent intellectual who returned in 2011 after a 20-year exile in London. In earlier interviews we conducted, he had played down what were then threats posed by radical Salafist groups. Their members were he said, like all Tunisians, "his children".

Gunman Yassine Laabidi was buried on Sunday

The experience of the ousted Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt is also now seared in his thinking and was a key factor in Ennahda's decision to relinquish power in 2014 in the face of rising protests over security and economic failures.

When I ask Mr Ghannouchi whether he shares concerns raised by some observers that a new anti-terrorism law under discussion could revive the old police state, he expresses confidence in the gains won by Tunisia's revolution as well as the importance of national unity.

"Tunisia is an exception in the Arab Spring and will remain the land where west and east meet democracy and Islam coexist," he replies.

"We will investigate the security failures and fix them."

An admission of security lapses has also come from President Beji Caid Essebsi, whose Nidaa Tounes party eclipsed Ennahda in last year's polls but gave its rival a small share in the new government.

The footage released by the Tunisian interior ministry shows two gunmen in the museum

"We need national reconciliation," the 88-year-old leader remarks in a televised interview with French journalists at the popular museum of ancient relics which has now been thrust into a harsh spotlight in Tunisia's modern history.

The readiness of Tunisia's leaders to overcome opposition within their own ranks to reach difficult political compromises has been a significant factor in a successful transition.

So is the strength of its society with its traditions of established trade unions and civil society groups.

'Optimistic'

Over the past few days in Tunis, I've heard the same defiant refrains from everyone from lawyers and footballers, to business executives and tour guides.

"We are still optimistic," affirms lawyer Samia Jlassi next to coils of razor wire and lines of police which now form a security cordon across the wrought iron gates of the Bardo museum.

"Tunisians will do what we can," she says in the midst of a group of female lawyers in their white trimmed black court robes during one of the now daily protests outside the museum. "But this is an international problem."

Many Tunisians tell you they want tourists to keep coming to help bolster their struggling economy, and they need assistance to strengthen their security forces. But they want threats of extremism, as well as any return to excesses of power, to "get out".

- Published20 March 2015

- Published19 March 2015

- Published19 March 2015

- Published19 March 2015

- Published19 March 2015