Kenya's stoic survivors defy al-Shabab

- Published

Some of the Garissa University students who were rescued comfort each other

"Now I'm okay," was about all Cynthia Terotich could manage, as she sat in the casualty ward in Garissa's hospital.

She had been contemplating the 50 hours she'd just spent crushed inside a tiny cupboard, hidden beneath a pile of clothes, with nothing but a bottle of body lotion to try to quench a raging thirst.

The sound of her friends being butchered in the courtyard outside echoed in her ears.

Cynthia, a 19-year-old student at Garissa's teacher training college on the edge of town, spoke with the studied politeness that I've encountered repeatedly in the past few days in this isolated town, on the hot, dry plains that stretch towards and over the seemingly notional border that separates Kenya from Somalia.

There have been plenty of tears from the survivors of Thursday's killings.

But when confronted by a foreign journalist, each student I met seemed too anxious to reach - more so than in any other similar situation I can remember - for some approximation of composure.

"I'm fine, thanks."

"Everything is fine now."

"Thank you for asking."

I am very wary of reading too much into such things. But I found their politeness increasingly unbearable.

I couldn't shake off the sense that it was somehow linked to the horrors they'd just endured; that it was a lingering echo of the instinctive, terror-driven restraint - a numbed obedience borne out of the purest desperation - that had allowed four gunmen to spend hours sifting, separating, taunting and butchering a huge crowd of young men and women.

The BBC's Andrew Harding said Cynthia needed a lot of convincing to believe she was really being rescued

These feel like bewildering times for Kenya. Not so much in Garissa. In this poor town on the banks of the slow, brown Tana river, the local ethnic Somali population is used to navigating the complexities of religion and identity.

They are proud Kenyans, but occasionally feel like second-class citizens, suspected by every passing, bribe-hungry policeman of supporting the Islamist militants of al-Shabab across the border.

But elsewhere, Kenya seems preoccupied by other matters; by its own hectic development, its increasingly confident, assertive sense of itself as a modern, industrialised, tolerant nation - albeit one with deep levels of inequality.

Seeking revenge

Al-Shabab - with its bombs, its medieval values, and blood-curdling threats - feels not just out of place here, but baffling. Something on which to turn one's back.

Perhaps that helps to explain why, despite the 2013 attack at Nairobi's Westgate mall, security in the capital remains noticeably lax.

At Wilson airport this week, a porter helpfully offered to smuggle my bag on to a plane without going through the scanners. When I asked him why, he shrugged and said: "Oh, I thought you were carrying guns."

And yet you could argue that Kenya's leaders must have known all this was on the horizon.

For two decades Kenya managed to live alongside one of the world's most anarchic countries. It took in vast numbers of Somali refugees, many of them lived in giant camps near the border, supported by the UN and international NGOs, and helping to stimulate the local economy.

But Somalia's chaos stayed, for the most part, outside of Kenya.

Survivors were eventually bussed back to their home towns, after camping out for two days

Then, in 2011, the government's patience snapped - partly due to a series of kidnappings along Kenya's tourist-dependent coast.

Troops were sent into Somalia and Kenya's government quickly found itself neck-deep in the murky world of clan politics and patronage, buffer zones, spheres of influence, and the need strike deals with "friendly" warlords.

Since then, al-Shabab has lashed out repeatedly at Kenya.

Revenge is part of it. But some would argue that the focus on Kenya is actually a sign of al-Shabab's current weakness, as it loses territory within Somalia to African Union forces and an increasingly confident central government, and seeks to project the illusion of strength elsewhere.

Then there is the fact that al-Shabab is no longer a purely cross-border operation.

It has established deep roots (as President Uhuru Kenyatta acknowledged again on Saturday) within Kenya - roots nourished by the activities of Kenya's heavy-handed security forces and by the growing sense of alienation felt by young men in marginalised communities along the Somali border and the coast.

Nationalistic urges

And then there is Greater Somalia.

It is no secret - indeed it is enshrined in the five-pointed star on the national flag - that Somalis have always cherished the idea of one day uniting all the ethnic Somali regions taken from it at the end of the colonial era - in Ethiopia, Kenya and Djibouti, along with Somaliland - into one Greater Somalia stretching across the Horn of Africa.

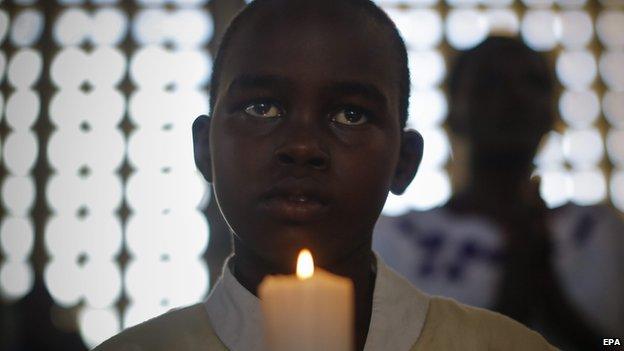

Ceremonies were held around Kenya for the victims on Easter Sunday

Al-Shabab may publicly espouse a global jihadist agenda, but it too is motivated by deeply nationalistic urges.

By attacking non-Muslim students in Garissa, the militants may well have been seeking - in their warped way - to promote the fortunes of Greater Somalia, by sowing divisions between ethnic Somalis and other Kenyans in the area.

Not that there was any hint in Garissa this week, that the militants were succeeding. Quite the opposite.

Yes, it was disappointing to see the way the surviving students were treated by the authorities here - forced to camp out for two days before being bussed out of town.

Surely they deserved better than that. One suspects wealthier students, at a more prestigious college, would have received more prompt support.

But overall such horrific incidents still seem more likely to foster national unity, to bring communities together in shared revulsion, than to divide.