Nigeria election: Savouring democracy

- Published

- comments

In our series of letters from African journalists, Mannir Dan Ali says many Nigerians can still not believe that they have succeeded in doing what just more than a week ago seemed impossible to achieve - to vote out an incumbent who accepted defeat, preventing an outbreak of violence.

On the eve of Nigeria's presidential election, residents of the capital, Abuja, were rushing to shops and markets to stock up on everything from bottled water and bread to other essential supplies.

This resulted in clogged supermarkets and queues at ATMs.

I was told that in one bank you could not withdraw more than 100,000 naira (about $500, £340) from your account in the week leading up to the 28 March electoral contest between President Goodluck Jonathan and opposition leader Muhammadu Buhari.

At one supermarket I went to, the shelves for bread were empty and there was a long queue of people waiting to get loaves being brought in hot from an adjoining bakery.

Civil war mantra

All this frenzy was because of the fear that the poll could result in violence, similar to that seen after the disputed 2011 election when some 800 people died.

The prospect of an upset in the 28 March election led many local and international groups to try to ease concerns of violence erupting by getting President Jonathan of the ruling People's Democratic Party (PDP) and Gen Buhari of the All Progressives Congress (APC) to sign a peace agreement and to pledge that they will abide by the verdict of the electorate.

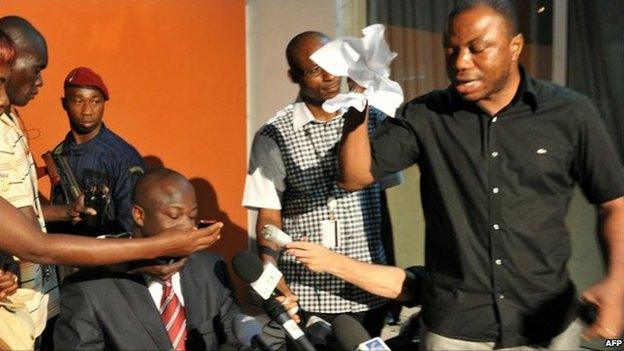

In Ivory Coast in 2010 the election results were torn up on TV

The two candidates straddled the religious and regional fault lines in Nigeria, with President Jonathan a Christian from the south and Gen Buhari a Muslim northerner.

The desperate campaign rhetoric had not improved the atmosphere with some highly provocative claims by the politicians.

There was a flurry of international intervention - most notably by the US.

President Barack Obama released a statement on the eve of the election reminding Nigerians that "to keep Nigeria one is a task that must be done", echoing the mantra heard after the 1967-1970 Biafran civil war which threatened to break up Africa's most populous state.

International Criminal Court (ICC) chief prosecutor Fatou Bensouda also had a clip repeatedly broadcast on some television channels, warning that those responsible for hate crimes committed during the election could be tried at the ICC.

TV drama

On the day itself, the permanent voter cards and biometric card readers introduced by the Independent National Electoral Commission (Inec) helped to sanitise the election and made it difficult for the 100% voter turnout that used to occur in the past - and through which dubious figures used to be returned as votes.

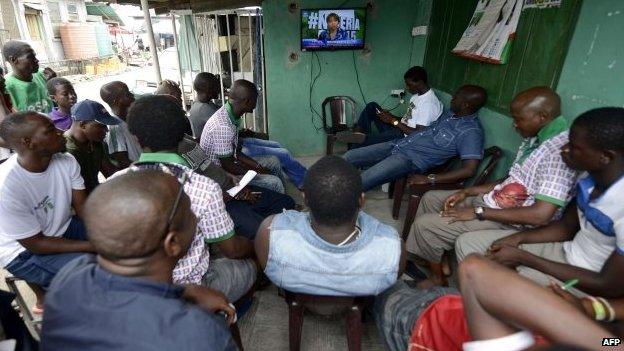

Nigerians were glued to the television watching the results broadcast live

With supporters of the two main candidates heavily mobilised, the vote passed off generally peacefully in spite of some minor hitches.

The one time when everyone in Nigeria held their breath was at the collation centre where results were being announced a few days later.

A PDP agent and a former government minister, Godsday Orubebe, nearly disrupted the whole process by accusing the electoral boss of bias - a charge he dismissed after a tense few minutes that seemed like hours to most Nigerians glued to their televisions and radios that were broadcasting the whole drama live.

Before the matter was defused, many Nigerians feared either a repeat of what happened in Ivory Coast in 2010 when the announcement of election results was halted and the result sheet was torn up live on television by a ruling party agent, leading to a brief civil war

Or a repeat of the Nigerian situation in 1993 when a court halted the announcement of results and the military subsequently annulled the poll, leading to a prolonged political crisis in the country.

'Come of age'

When it emerged later that day that President Jonathan had called and congratulated the opposition candidate and conceded defeat, Nigeria erupted into celebrations several hours before the formal announcement was made by Inec that Gen Buhari had won the election by a margin of more than two million votes.

Dangerous stunts by those celebrating the result led to some accidents

It is a sad irony that the scores of deaths which followed were not as a result of political clashes, but the reckless way in which some people were celebrating the victory through dangerous driving and other stunts.

And while some of the credit for the historic week must go to the electoral commission and to a president who found a redeeming feature in a generally lacklustre term in office, it was also the Nigerian people who were determined to show they had come of age.

They are savouring the fact that they have broken the jinx that an incumbent cannot be defeated through the ballot box.

These strengthened democratic credentials leave a sweet taste for Nigerians and should also be as a warning to the president-elect that it is no longer possible to take the voters for granted.