Inside Mali's human-trafficking underworld in Gao

- Published

The city of Gao in north-eastern Mali is the gateway to the Sahara for many African migrants seeking to get to Europe.

But crossing the desert can be as dangerous as crossing the Mediterranean - and a group of young men in a backstreet compound sit nervously and in silence.

In one corner of the walled yard is a pile of five-litre jerry cans, each with a sackcloth cover and strap.

When the next truck is ready to head out into the desert, the containers will be filled with water and given to the dozen migrants.

Each has paid up to $400 (£270) for the uncertain ride to Algeria. They look frightened and confused; most are unable to understand the French that is being spoken.

The place is called "the ghetto". It is at the heart of Gao's human-trafficking underworld.

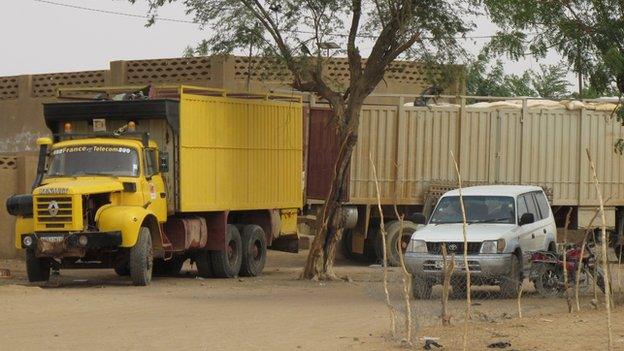

The migration business is the mainstay of Gao's economy

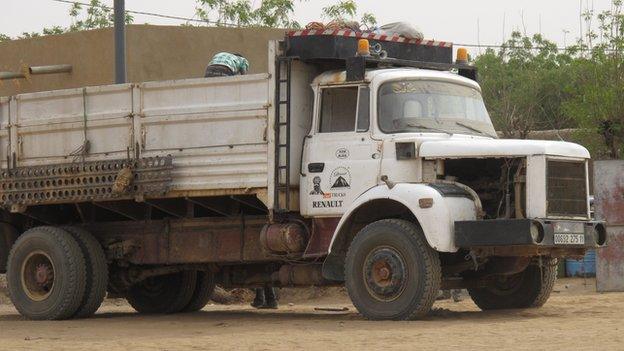

Trucks come south to deliver goods to Gao and often head north with migrants

Hundreds of African men dreaming of a future in Europe pass through one of Gao's three "ghettos" every month.

Some 2,000km (1,240 miles) from the Mediterranean coast, Gao is the last point of relative safety before a six-day truck journey through the desert that claims an untold number of lives.

Sardou Maiga, bus station mechanic

They may die on that journey because if there are difficulties, the drivers will just drop them in the desert along the way

''I reckon the migrants have a 10% chance of reaching where they want to go. But the way I see it, it's their choice,'' says Moussa, a 26-year-old ''coaxer''.

His job is to board the passenger buses arriving from southern Mali and earmark migrants for his ghetto boss.

''You get on the bus about 20km before Gao. You walk between the seats saying you've been sent by Abdoulaye or Ibrahim - any common Malian name will do - and you are there to look after their onward journey.

"The guys put their hands up,'' says Moussa, who receives 5,000 CFA francs ($10) for each migrant he takes to the ghetto boss.

'Cocaine Town'

Gao is a low-rise city with broad, dust-red streets.

Its economy is based largely on trafficking; humans are traded here like fuel barrels and boxes of noodles or fridges from Algeria.

It is a known transit point for the lucrative trade in South American drugs, to the extent that it has a suburb known as "Cocainebougou" - Cocaine Town - where two- and three-storey concrete villas rise incongruously out of the dusty surrounds.

Trafficking networks prey on the migrants' fatigue and ignorance of geography

Because so much is at stake, Gao saw some of the worst fighting when rebels under various banners - Tuareg secessionism and Islamism - swept through northern Mali in 2012, prompting a French military intervention the following year.

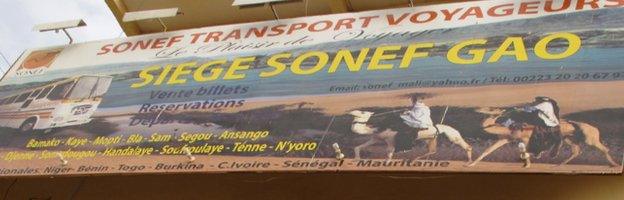

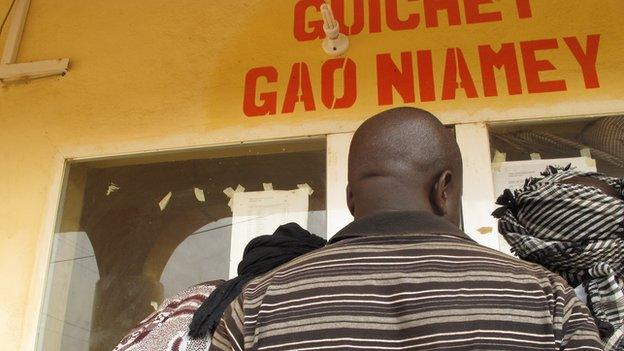

The touting that goes on aboard the coaches before they even reach Gao explains the relative order at a bus garage run by Sonef Transport in Gao.

I see three young men, with hardly any luggage and dressed in clothes that have clearly been slept in, being whisked into a taxi.

Sahara trafficking routes

Chief mechanic Sardou Maiga says the trafficking networks prey on the migrants' fatigue and ignorance of geography.

"The ones you have just seen mostly have bought bus tickets from Bamako [Mali's capital] all the way to Libya. We run a bus service to Niamey [the capital of Niger] and onwards to Arlit on the border with Libya," he says.

"But the travellers have to change buses here in Gao and that's when the coaxers divert them and sell them to Tuareg truckers going to Algeria.

"They may die on that journey because if there are difficulties, the drivers will just drop them in the desert along the way."

Theodis Windel Dennis, 26, from Liberia:

I had $1,100 when I left Liberia one week ago. It's gone now. I went to Senegal where I paid $400 for a ticket to go to Morocco. But I was tricked. There was much more to pay later. So I went to Bamako and paid for transport all the way to Algeria.

There were 15 to 20 checkpoints all the way through Mali. At each the Malian army harasses you for money - you have to pay between 1,000 and 5,000 CFA francs or they take you off the bus.

When the bus arrived in Gao I was robbed of my bag with my phone, the cream for my hair, the rest of my money and my passport. But I am going to keep moving… I need to find a job in Algeria.

I want to go to Europe; I want to work for money. I am educated; I am a high school graduate. My mother is very old, my father has died, so I found it difficult in Liberia. I don't care if it's dangerous; I am not afraid. I just need to get out of Africa.

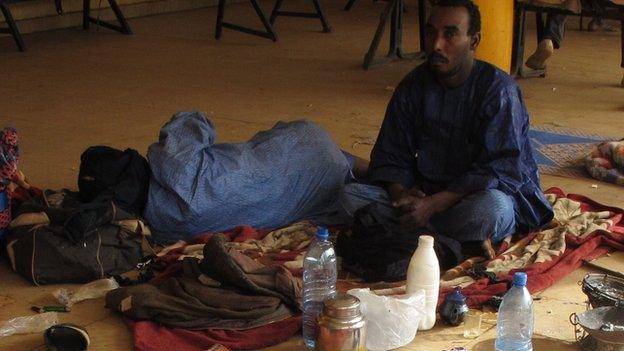

Ibrahim Miharata, 45, runs Direy Ben, meaning "the journey to fortune is over", a hostel for migrants who are down on their luck.

It receives funding from the Malian Red Cross and the Roman Catholic Church and can accommodate up to 70 migrants.

'Shameful to return'

He says he has seen a lot of Gambians lately.

Many migrants are unaware of the risks of the desert journey

"Many have backtracked after being put off by the war in Libya," the hostel manager says.

"When they come back to Gao they are often desperate and sometimes mentally disturbed.

"Imagine someone who left his family a year ago. The family sold two head of cattle to support his trip.

"He was given $800 or $1,000. And now he is facing going back without a penny. It's shameful. It's enough to drive you mad."

Mr Miharata reckons up to 900 African migrants pass through Gao each month and head out on trucks up the road to Kidal and the Sahara, bound for Tamanrasset in Algeria.

Others - those who stay on the Sonef buses - continue eastwards towards Niger and Libya.

Hundreds of migrants pass through Gao each month

Some head to Niger on buses and then to Libya

Others head in trucks to Tamanrasset in Algeria and then either to Morocco or Libya

"The reason Gao is a key transit point for trade is that it offers one of the cheapest and shortest desert crossings - about five or six days," Mr Miharata says.

"So even if you come from Eritrea you might find yourself crossing the desert from here. It all depends what advice you get along the way."

Ibrahim Miharata, Gao migrant hostel manager

If you want to make a living in Gao, the migration business is your only choice

He estimates that Nigeria, Cameroon and The Gambia are the top three countries whose young men - mainly - are leaving the region this way.

"It is hard to be categorical because migrants lie about where they come from. The majority are definitely English-speakers, though."

Although he runs a hostel for distressed migrants, he owns a green bus, which runs to and from Kumasi in Ghana.

"Direy Ben helps those in distress but I am a former migrant myself - I went to Tunisia and Ivory Coast in my time - and I am in favour of the free circulation of people,'' Mr Miharata says.

"If you want to make a living in Gao, the migration business is your only choice."

- Published3 December 2014

- Published25 April 2023