Sahara screenings: World's most remote film festival

- Published

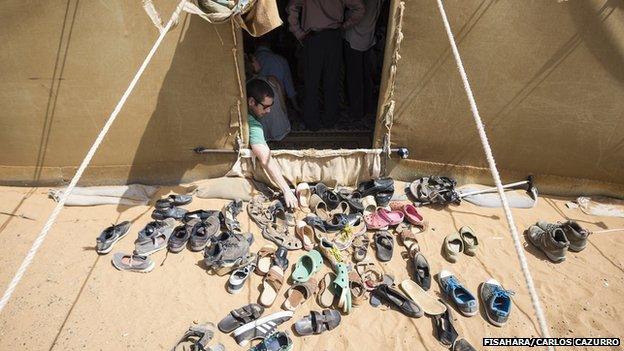

This is the world's most remote film festival - in a refugee camp in the Sahara desert, where nothing grows and few people visit.

The sun is so scorching in Algeria's Dakhla camp - over the border from the disputed territory of Western Sahara - that equipment, including solar panels, can melt in the heat.

The wind is so strong that it can blow down tents and families are forced to shelter in concrete toilet blocks.

But the Western Sahara International Film Festival (FiSahara) has drawn Hollywood stars, like James Bond film actor Javier Bardem, to what residents call the end of the earth.

They have come to hear the stories of the Saharawi people, whose 40-year struggle to call Western Sahara home again would otherwise be completely buried.

The African Union recognises the independence of Western Sahara, but most of it remains under the control of Morocco, which annexed it in 1975 after Spanish colonial forces pulled out.

Morocco maintains it has a historical claim to the territory and has offered it a degree of autonomy.

It is a long journey to get to Dakhla from the Spanish capital, Madrid.

Some 30,000 people live at the Dakhla camp

First a charter flight and then a military-escorted convoy of rickety buses bumping across the desert for hundreds of kilometres until it reaches a tiny strip of lights which illuminate the refugee camp.

The time is nearly 03:00 but host families are there to greet guests, take them home and serve dinner before offering either a bed inside a tent or a blanket for sleeping outside.

FiSahara organisers bring the equipment and a planeload of actors, human rights activists and journalists to this desert.

But festival director Maris Carrion says the Saharawi people are the stars of the show.

They fled Western Sahara in 1975 after the end of Spanish rule - and have been in southern Algeria ever since.

The refugees would move mountains to get the world's attention.

There is much razzmatazz...

During the six-day desert festival

"The last thing that people want to feel like is forgotten, and stuck in an interminable situation of refuge and injustice," Ms Carillon says.

The festival keeps children wide-eyed until the small hours, with films projected onto the side of a lorry that makes a screen under the stars.

Giggles about cartoons and light-hearted short films made by refugee teenagers ripple through the rows of people sprawled on blankets.

'Time for peace'

But there are tears too, as the Sahawari see the bigger picture of their stories of torture, disappearance and abuse, or empathise with the similar fates of others in films from Latin America to Asia.

Saharawi people feel ignored by the world

About 30,000 of up an estimated 165,000 Sahawaris live in the camps, hours away from a heavily mined and guarded wall that separates them from relatives in Western Sahara.

There is a promised referendum on the status of Western Sahara but it has been frequently delayed.

The youth here appear to be tiring of the peaceful resistance to a conflict that the world ignores, but Khadija Hamdi, Western Sahara's culture minister in-exile, said that it still has a role.

"This festival is a peaceful demonstration that allows the Saharawi people to be heard," she said.

The festival is an opportunity for fun and debate

Workshops are held and the refugees' plight considered

"Yes, the youth have the right to return to armed struggle, but we the leadership still believe that there is time for peace."

Nearby, a workshop led by Saharawi rapper Yslem has convinced 15-year-old Ahmed Salem to fight for his rights with art, not arms.

"We don't like what the Moroccans are doing," he says.

"I want to become a revolutionary to fight them in a war, but a war of words, that we will slowly win."

Lawyer Michael Ratner, who is famous for taking on the US government over Guantanamo and Iraq now wants to take on Western Sahara's case, but says that documentaries will sway public opinion.

"What a film can do is bring out with real people what's happening in a particular place. So I believe very strongly in film as one of the modes of struggle."

Whether or not Western Sahara's revolution remains cultural, it will be televised.

- Published28 October 2024

- Published21 September 2014