Yemen conflict: A passport out of war

- Published

- comments

A human tide reaches the shores of Djibouti almost every day.

Waves of Yemenis are taking to the sea in packed yachts or wooden dhows meant to ferry fishermen or livestock, not a people fleeing for their lives.

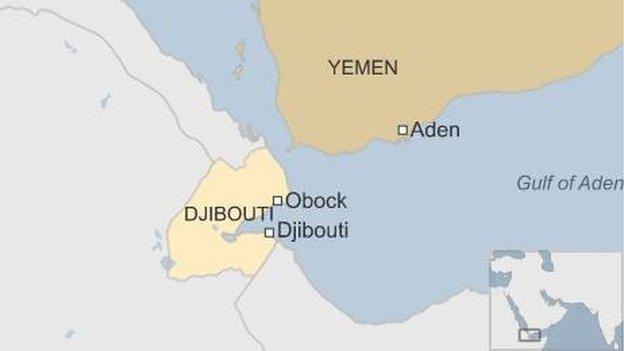

The boats dock in Djibouti's main harbour or the miniature port of Obock further north, a jumble of rocks just 30km (19 miles) across the Red Sea from its neighbour torn by war.

"Schools are closed, colleges are closed, sometimes hospitals are shut because there's no electricity. It's so dangerous," laments 22-year-old Salma al-Shabib, who crouches by a wall as she waits to clear immigration at Djibouti port.

Like almost all the women seeking shelter from the searing heat, she's completely covered in black, except for a small slit that reveals anxious brown eyes.

But Selma hopes she has a powerful weapon in her battle to escape: her father has an American passport and he's coming to pick her up.

"I will be safe," she vows, "in the United States of America."

Selma and family - Yemeni refugees in Djibouti port

Many who made this hazardous 18-hour journey, just before a temporary ceasefire expired, came from the Yemeni city of Ibb and brought their American connection with them.

Jaber is still sporting his moss-green tracksuit emblazoned with the words Michigan State.

After surviving threats from Houthi rebels, who now control most of Yemen, he looks forward to more orderly business in the West.

"We have an appointment in a different country," he says cryptically about his next stop to take his family back to America.

"I put my life at risk to get my family out of Yemen, " he recounts with palpable relief. "It's extremely dangerous. The Houthis point their guns at you and check everyone, even the kids. But they're just kids with heavy-powered machine guns."

He glances across a crowd of hundreds of hopeful migrants.

"Thank God I have money and stuff to take me somewhere else."

Airport bombed

A young man in jeans and a polo shirt also approaches, grateful to vent his frustration, but wary about disclosing his name.

"I've been sleeping for the past two nights in a hangar in this port with 100 other people," he moans. "The American Embassy won't give me back my passport until I find a hotel room."

The 18-year-old American left New York five months ago to meet his new Facebook friends in the land of his father's birth.

The modern magic of social media was no match for Yemen's age-old battles for power.

"I tried to leave three weeks ago, but the airport was bombed," he says, referring to the Saudi-led air strikes unleashed in March to confront the growing sway of the Houthis.

Arrival point at port for Yemenis who have escaped the fighting

By the time we reach the hangar a short walk away, darkness has descended and a gravel yard is full of men of all ages sprawled across thin mattresses.

The relative stillness of the night brings out conversation and khat: bulging plastic bags of the green-leafed stimulant are ubiquitous in Yemen and beyond.

The scene inside, where high plastic sheets separate men from the women, is much the same.

One man lifts an arm to show a medical certificate attesting to his ill health.

Another, sounding delirious, holds out a sheath of photocopied passport pages and an email which confirms he was granted an appointment at the German consulate in the capital Sanaa. But war got in the way.

"I've been here for 20 days," another man announces as a crowd quickly grows. "I don't have my American passport with me and they can't find my name."

An anxious young man next to him interjects. "I have a Yemen passport," he declares. "For me, this port is a jail. I can't leave without a visa."

Scorching heat makes the waiting in Djibouti port all the harder

'Anywhere but here'

A few hours' drive north, a refugee camp taking shape in Obock is a signal that waiting may become a way of life.

Neat lines of dusty tents loom like an eerie ghost town in the desert.

Hundreds of refugees are hiding inside from a new enemy: the scorching heat.

But our arrival, along with a young UN official in her signature blue shirt, draws a crowd and, with it, a torrent of anguish.

"I totally understand," says the infinitely patient Marie-Claire Sowinetz, of the UN's refugee agency, the UNHCR.

She's bombarded with pleas: an elderly woman complains bitterly about the new food rations which are now replacing hot meals; young men beg to go anywhere but here; a well-spoken female lawyer loudly deplores "this miserable life".

"Weeks ago, many of these people lived in air conditioned apartments in Aden and now they find themselves in a refugee camp in a tent," Ms Sowinetz explains.

"For now, we're focusing on this emergency and passing on people's information to embassies."

Abdul Hussain, from Birmingham, was caught up in the chaos in Yemen

My colleagues and I suddenly realise we already know a bit about one man in the crowd - Abdul Hussain, from Birmingham.

He crossed paths with a BBC team in the southern Yemeni city of Aden last month as he was desperately trying to get back to Britain with his wife.

A bear of a man, his strands of curly hair are frizzy with the heat, his nerves frazzled with the wait.

He tells us he spent 20 days at Aden port, 20 days at Djibouti port, and now ten days in this camp.

"Some days I lose hope," he sighs. "But on other days, I hope someone out there will help me."

In a tent which feels like a big oven, I meet his wife Zubaidah. Her Yemeni passport means their case is caught in Britain's restrictions on bringing in foreign spouses.

In this high-stakes lottery of war, the right passport is often the only winning ticket.

"Maybe we'll have to go back to Yemen," Abdul Hussain regrets.

"The war was killing us, but now we're dying from this heat."