Why South Africa let Sudan's Bashir escape justice

- Published

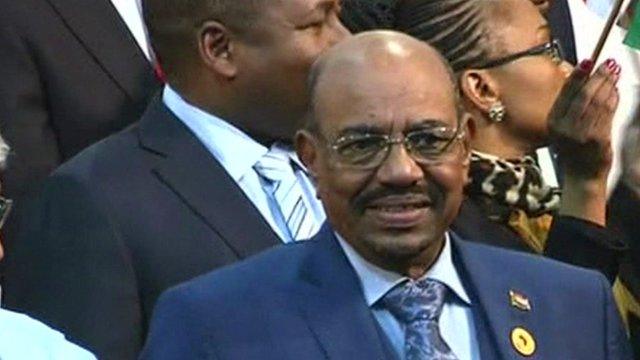

Cheering supporters greeted Mr Bashir at Khartoum airport when on his return from South Africa

South Africans are angry at their government for flouting the country's laws.

It was very clear from the beginning that South Africa would not only be breaking international law by allowing Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir to fly out of a military base but would be going against its own courts.

In a constitutional democracy such as this one, it could be argued that President Jacob Zuma should have not allowed Mr Bashir to come into the country in the first instance.

And many are questioning why South Africa decided to violate its own obligations to the International Criminal Court (ICC), which wants to try Mr Bashir on charges of genocide and war crimes related to the conflict in Darfur - charges he denies.

The answer perhaps lies somewhere between a former liberation movement's nostalgia for being defiant to the West and a lack of strategic thinking.

Darfur conflict: Key points

The conflict in Darfur has forced more than a million people from their homes

Fighting began in 2003 when rebels in Darfur took up arms, accusing the government of neglect

Pro-government militias, known as Janjaweed, accused of responding with ethnic cleansing

In 2008, the UN estimated that 300,000 people had died because of the war, though Khartoum disputes the figure

More than 1.4 million people have fled their homes

In 2010, the ICC charged President Bashir with genocide in relation to the Darfur conflict

There have been several peace processes, but fighting continues, with numerous armed groups now active

But South Africa's own standing in Africa may be another, more complex, reason for its defiance.

The recent xenophobic attacks on fellow Africans diminished South Africa's status amongst African peers.

The country as a whole, from government to business, has been hard at work trying to recover lost ground from that embarrassing episode.

'Unthinkable'

Africa was not just disappointed by the behaviour of South Africans, it was angry.

At least seven people died in over a month of attacks on foreigners and foreign-owned property.

Xenophobic violence has tarnished South Africa's image in Africa

Many countries repatriated their nationals who felt too afraid to stay in South Africa.

So the idea of arresting a sitting head of state so soon after the violence was simply unthinkable.

It would have been considered a colossal failure of judgement when it came to maintaining cordial relations with the rest of the continent.

In 2010, before the ICC added genocide charges to its arrest warrant for Mr Bashir in relation to crimes of humanity allegations in Darfur, the AU sent a communique to the UN Security Council asking for proceedings to be deferred until a political solution was found.

The Security Council did not reply, and this, according to law professor Bonita Meyersfeld, was when the antagonism between the AU and ICC was born.

She told the BBC that the weekend drama was "a devastating moment for South Africa's democracy, with such a blatant disregard of its own laws".

Critics of the ICC should not be asking whether the court was unfairly targeting Africa, the University of Witwatersrand lecturer said.

Mr Bashir's supporters carried a mock coffin of the ICC after he returned to Sudan

"The question is: Why is the ICC not holding people from the developed world criminally accountable?"

I pressed her to give examples: "The obvious suspects are [former UK Prime Minister Tony] Blair and [former US President George W] Bush who are in contravention of international law over the invasion of Iraq."

The UK government at the time said it received legal advice that the invasion in 2003 was lawful.

Ms Meyersfeld added that "Russia for its actions in Chechnya and Israel and Palestine" were other cases that deserved attention.

But the fact that ICC's scales seem unfairly tilted against Africa does not mean that South Africa, which is this week commemorating the youth anti-apartheid uprising of 1976, should violate its own court order.

- Published16 June 2015

- Published15 June 2015

- Published14 August 2019

- Published15 June 2015