Why Tunisia has been targeted

- Published

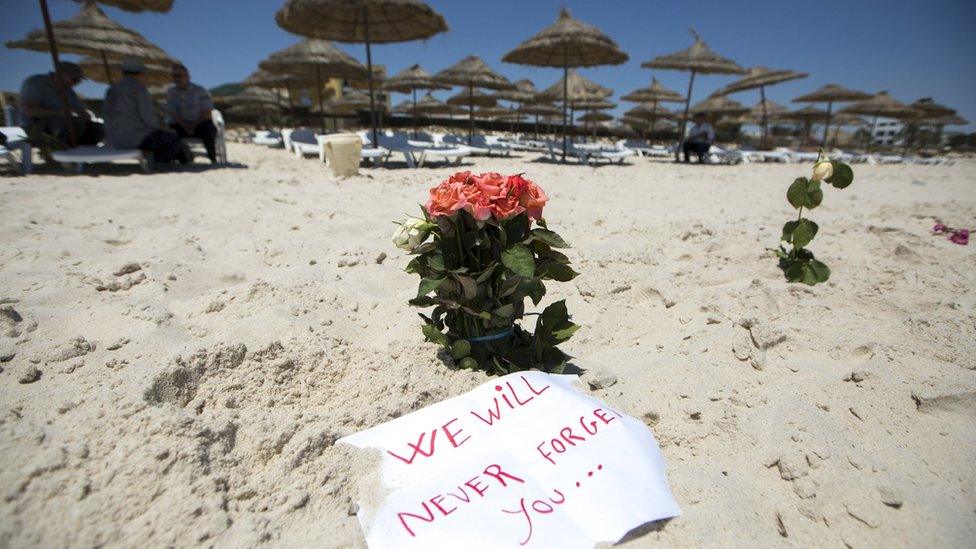

The attack is expected to hit Tunisia's tourism industry hard

The attack that killed 38 people in the resort city of Sousse has left Tunisia looking particularly vulnerable.

It was a devastating blow to a country still struggling to recover from another attack on tourists in the heart of its capital just three months earlier.

And it was claimed by Islamic State (IS), whose actions have spread fear throughout the region and beyond.

"We note that Tunisia faces an international movement," Tunisian President Beji Caid Essebsi said shortly after Friday's attack. "It cannot respond alone to this."

While much remains unclear about the extent and nature of the threat within Tunisia that the events in Sousse may expose, observers have pointed once more to two specific risks.

First, the threat posed by neighbouring Libya, a fractured country with porous borders that has been awash with weapons since the fall of Muammar Gaddafi, and where Islamic State now has an established presence.

And second, the apparently large number of Tunisians who have left to fight in Syria and Iraq, hundreds of whom are estimated to have returned home.

Other countries in the region also face cross-border threats, and it is hard to get a truly accurate idea of how many Tunisians have been radicalised fighting abroad.

But Tunisia appears to be more exposed than its neighbours to high-impact attacks against foreign civilians.

Neither Libya nor Algeria have mass tourism, and though Morocco does, it also has a pervasive security network and has been politically stable.

Tunisia, by contrast, has a "big, soft underbelly", said Geoff Porter, the head of North Africa Risk Consulting.

"I don't think Tunisia does have a disproportionately greater jihadi problem than Algeria or Morocco," he said. "What Tunisia has is a security problem.

"It's simply that there are a greater number of targets in Tunisia and the security forces are less effective."

Full coverage of the Sousse attack

Before the uprising of 2011, the focus for those security forces was enforcing control under former President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali - a job at which they were long efficient, developing a vast web of informers.

But security reform has been slow, and the challenge may now be for the police to repurpose towards counter-terrorism work, Mr Porter said.

That will be a complex task, partly because of the demands of training and equipping police officers and soldiers, but also because of the democratic political process and the fine line between ensuring security and reverting to repression.

Tunisia has said it will deploy soldiers and armed police to tourist sites

In a cruel twist, some contend that Tunisia has been targeted partly because it has achieved a democratic transition and is often held up as the single success story of the Arab Spring.

Its progress as a modern democratic state on friendly terms with the West, if halting, is unwelcome to the militants of Islamic State and other extremist groups.

Over the last four years, Tunisian governments are seen to have vacillated between granting radical Islamists political space and cracking down on them - only taking the latter course more decisively after the assassination of Chokri Belaid in February 2013.

A new Tunisian anti-terrorism law that would broaden police powers and provide for harsher penalties has been stuck in committees since the start of 2014.

The attack in March on the Bardo Museum - next to the parliament building - focused attention on the bill, but shortly after it was redrafted, 13 non-governmental organisations called for it to be dropped or amended, external, saying it would violate international human rights standards and guarantees under the Tunisian constitution.

The president of the Tunisian parliament now says it will be approved within the next month.

Then there are the broader internal challenges.

The Tunisian economy has become more fragile since 2011, and like other states in the region, the country has a large pool of unemployed or underemployed young men who may be susceptible to radicalisation.

As Sayida Ounissi, a Tunisian member of parliament from the Islamist Ennahda party, told the BBC: "What we are seeing today is terrorism is actually nourishing itself from social exclusion, from economic injustice, from the lack of education."

In the short term, the number of potential recruits is only likely to grow as the tourist sector - which accounted for about 15% of GDP last year - takes another big hit.