Letter from Africa: On Buhari and forgiveness in Nigeria

- Published

In our series of letters from African journalists, novelist and writer Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani considers Nigerians' tendency to forgive past misdemeanours and what it means for the country's new president.

In Nigeria, it is quite common that if you fire someone for gross misconduct, that person will turn up days later in the company of his or her grey-haired, widowed mother and maybe an aged uncle and a pregnant wife.

Together, they kneel at your doorstep and beg you to forgive, promising that the recalcitrant person will act differently if re-employed.

Sometimes, the sacked person will phone you two months later to say that he or she has been offered employment elsewhere, then beg for a positive reference, while reminding you that the same people you meet on your way up, you shall surely meet on your way down.

More likely than not, the repentant former employees are given a second chance.

Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani:

"My Nigerian-American friend is horrified by this Nigerian culture of wiping clean people's track records"

Nigerians are usually willing to give others the opportunity to prove that they have transformed, no matter how grave their previous errors.

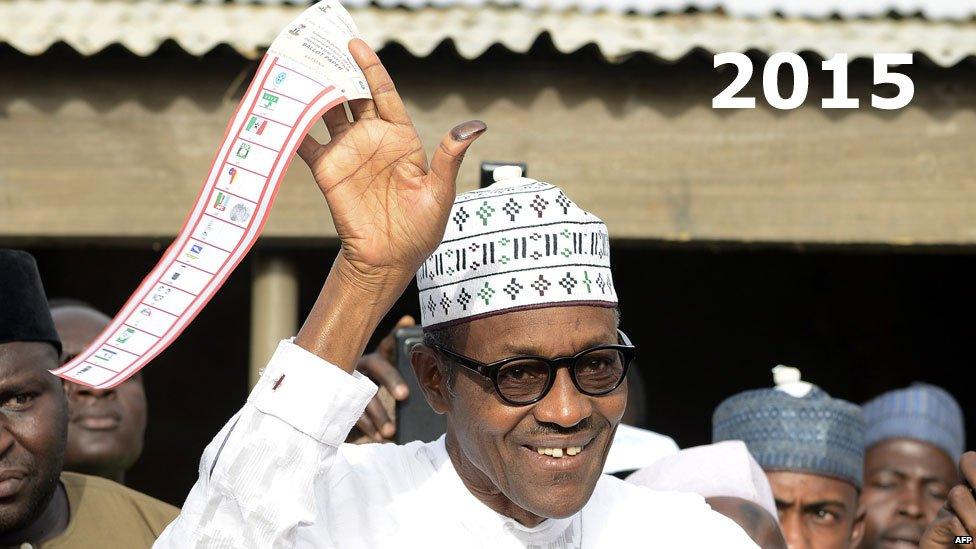

One of the most recent, high-profile beneficiaries of this second-chance culture is Muhammadu Buhari, Nigeria's new president.

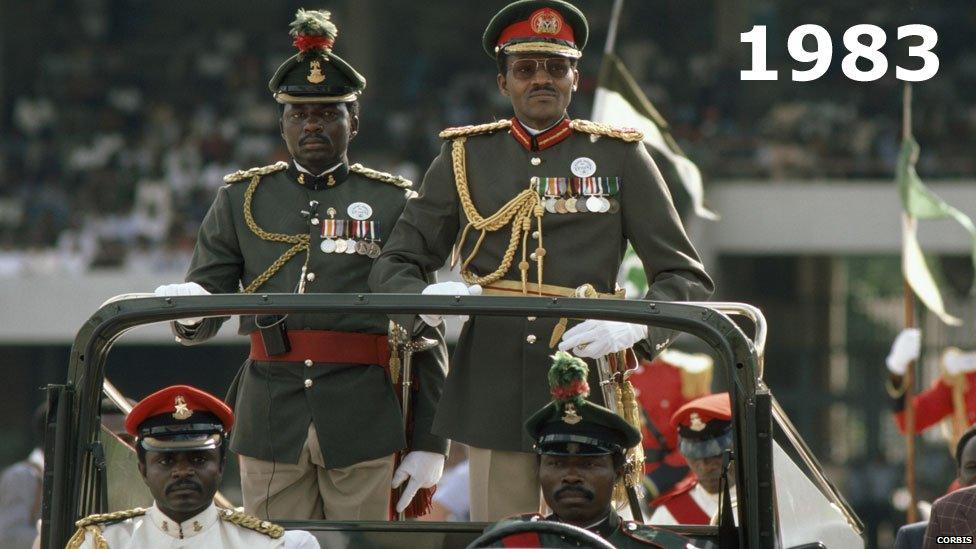

Back in 1983, he brought the country's then fledgling democracy to an abrupt end via a military coup, and his 18-month rule was infamous for draconian policies and human rights violations.

While campaigning for the 2015 elections, Gen Buhari assured Nigerians that he was a changed man, that he was well aware of the difference between dictatorship and democracy.

Many prominent citizens who had suffered in one way or the other under his rule responded by openly declaring their forgiveness for the retired general.

Politician Audu Ogbeh and journalist Tunde Thompson, who were incarcerated under President Buhari's military regime, became active members of his 2015 campaign committees.

My Nigerian-American friend is horrified by this Nigerian culture of wiping clean people's track records.

She describes her experience as a first-year student at Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, where the careers counsellors often spoke about the close-knit circle in corporate America, and how easy it is to get blacklisted by all firms based on bad behaviour or poor performance at one firm.

The students studied the stories of two alumni who had brought shame and financial ruin to their companies because of their unethical behaviour.

"I remember the moods in the lecture rooms after each of these sessions," she said, "when we often swore to ourselves that we would never become subject material for case studies on ethical failures."

No such case studies are taught in Nigerian schools.

A disgraced CEO here could easily get hired in another high-profile role.

Yesterday's vilified plunderer of public funds could metamorphose into tomorrow's icon of philanthropy and champion of the masses.

Radical policies wanted

But, one month after President Buhari's inauguration, a paradox appears to exist in the forgiveness extended towards him.

Nigerians claimed to have forgiven him for the man he used to be, yet are expressing disappointment that he is not that same man they thought he was.

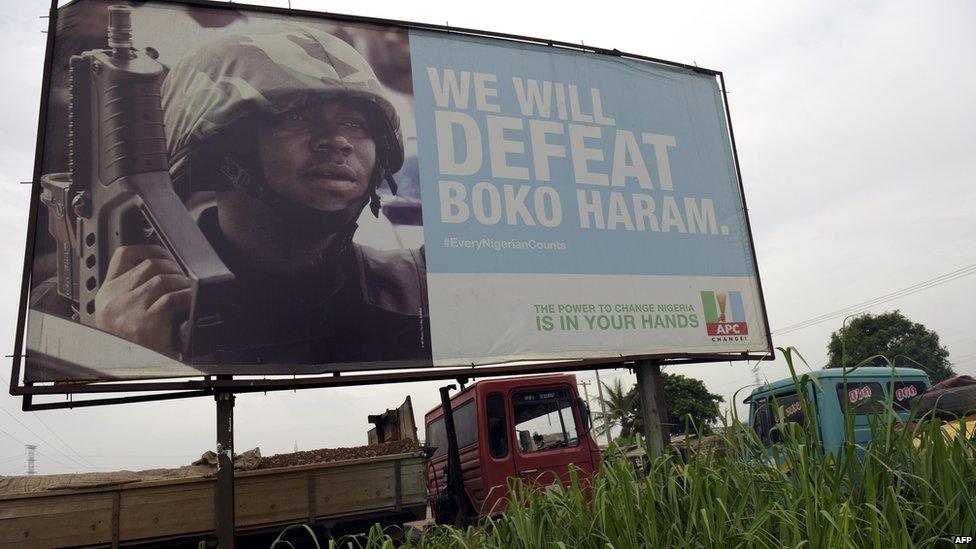

They seem to have expected President Buhari, on assuming power, to immediately act tough: To send corrupt government officials straight to the guillotine; to initiate probes and commissions of inquiry; to announce radical policies; to order arrests; to drop bombs on Boko Haram.

President Buhari has promised to deal with the Islamist insurgency in the north

So far, President Buhari has done none of these things.

He says he is consulting and assessing.

He has not appointed the squad with whom he is expected to zap the nation clean.

He has not shown any open interest in political machinations, appearing indifferent even to the vitriolic squabbling engulfing the country's National Assembly.

President Buhari is clearly a changed man.

And Nigerians have started grumbling, in daily conversation and in the media.

They want their new president to get a move on. They want to see some action.

They want a bit more evidence of those revolutionist traits for which he became infamous, and then famous. They want some of the old Buhari. They want the man they forgave.