Tunisia tourism: The past, present and future in Sousse

- Published

In 2014 tourism made up around 15% of Tunisia's economy

Now that the UK government has urged Britons to leave Tunisia in the wake of June's gun attack in Sousse, there is a question over whether the tourist industry can recover. The BBC's Rana Jawad has been to Sousse to meet those whose lives are deeply entwined with welcoming foreigners to the town.

Sousse was the first city to introduce tourism to Tunisia, where it is now one of the biggest sectors.

but an eerie silence on the sea front has replaced the happy hum of a throng of tourists that would normally be heard at this time of year.

A few metres inland, there is a sadness echoing through the old city's abandoned alleyways dotted with idle vendors.

The halls of hotels are mostly occupied by shell-shocked staff members facing an uncertain future.

Here, three generations of Tunisians working in the tourism sector recount their stories:

The past

A small tourist industry already existed during the colonial era

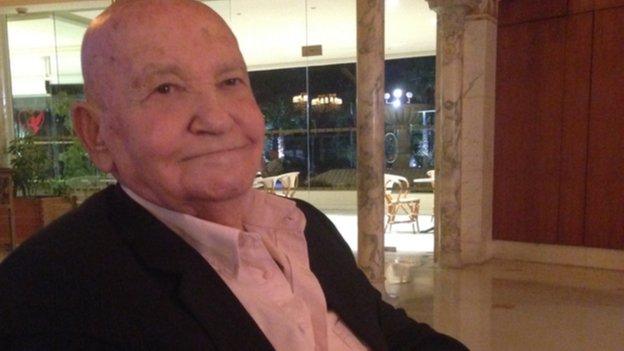

Mohamed Idriss, aged 92, was among the pioneers who started mass tourism after the country emerged from colonial rule.

He sits upright with a cane by his side in the gleaming lobby of Bourj al-Khalaf - one of 20 hotels he and his family own in Sousse.

He comes every night to sit in his office - it is perhaps an ageing man's way of staying connected to a legacy he started.

Mohamed Idriss's family have not told him about the gun attack

Mr Idriss built the first of what would become the Marhaba chain of hotels in 1964, a family business he still oversees.

The Imperial Merhaba - run by his daughter Zohra Idriss - was the scene of June's deadly attack.

He does not know about the gunman's deadly rampage as his family were not sure how to explain it to him.

Mr Idriss is a softly spoken man with a fading memory that belies the strength and confidence he displays.

"I am the first person who established tourism in Sousse, not one of the first," he says with a faint smile.

"There was nothing in Sousse before tourism was developed. And no-one had thought about building hotels… I saw the newspapers writing something about it and I said to myself: 'Why not try this?'"

Locals enjoy Sousse beach in the days before the advent of mass tourism

In the 1960s, tourism was of little significance in Sousse, as Mr Idriss explains: "Some thought it was a good idea and some thought it was bad [but] today you'll find that every businessman has thought about tourism."

The city's wealthy families and other local entrepreneurs followed suit and went on to develop the tourism sector, and it remains an industry still dominated by people from Sousse.

The present

Fifty years on from the first tourist hotel, Sousse bears the hallmarks of any Mediterranean resort: Large hotels, discos, bars and fast-food joints with big neon signs.

Loutfi Soula runs the Soula Centres, four big shops catering almost exclusively to tourists. His most popular is on the edge of the old city and sells everything from traditional carpets to bikinis.

Along with his brother, Mr Soula started off by selling traditional Arab gowns, known as jalabiyas, from a tiny shop in the old city in 1981.

Loutfi Soula is worried that he may have to close some of his shops

A decade later he opened the first Soula Centre "selling all kinds of things like olive oil, ceramics, copper, leather and souvenirs and business developed automatically", he recalls.

There was a dip in visitor numbers in the aftermath of the 2011 revolution which overthrew Tunisia's former dictator Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali, it started recovering last year but this latest attack in Sousse has struck at the core of the sector.

The murder of 38 tourists has made some people nervous about visiting Sousse

Mr Soula is now worried.

"We are not sure if we will have more tourists. This year there will be no business [and] I'm starting to think about closing one or two stores, because we can't pay all the costs, we have almost 350 members of staff."

He takes me on a tour of his sprawling gallery and shows me the roof where he is building a cafe. He says he is considering stopping work on it because of the lack of visitors.

"Terrorism is difficult… these are crazy people who are destroying the economy."

The future

What then for the tens of thousands of Sousse's young people who have set their eyes on the tourism sector?

Wael Toumi will this year get a diploma from Sousse's tourism institute.

He emphatically states that in Sousse, there are three career options: "Tourism, casual labourer or no job".

Like others, he is incensed by the gunman's attack. He was working at a nearby hotel when it happened, but he has not yet decided whether to look for an alternative career.

Tourism student Wael Toumi remains optimistic the sector will revive

"I won't make a decision now, I will finish my studies and then I'll see," Mr Toumi says.

Some have already lost their jobs after a flood of hotel cancellations.

"I have to be optimistic because I just know we have to work through the hell to reach heaven. You have to be patient. "

"Tourism for Sousse means 40,000 jobs, so if tourists disappear, it means 40,000 will be jobless."