What has Obama's visit done for Africa?

- Published

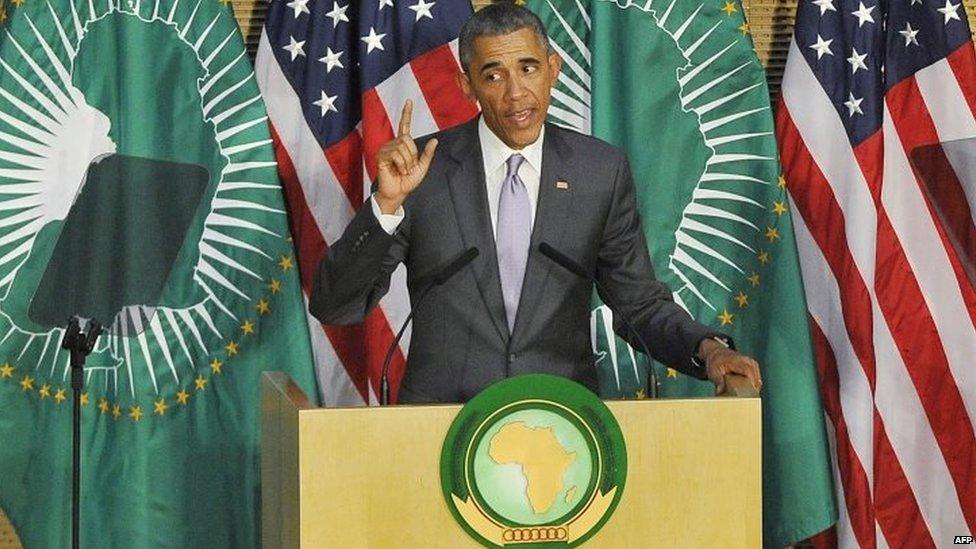

President Obama was the first US leader to address the African Union

When Barack Obama stepped off Air Force One in Kenya it felt like a moment of affirmation and an opportunity to use the US president's words to "call on the world to change its approach to Africa".

As a continent, it depends less on aid now than it did in the past. Instead many countries which make up Africa are increasingly being seen as a global partner, not a minority shareholder in generating wealth, fighting terrorism and climate change.

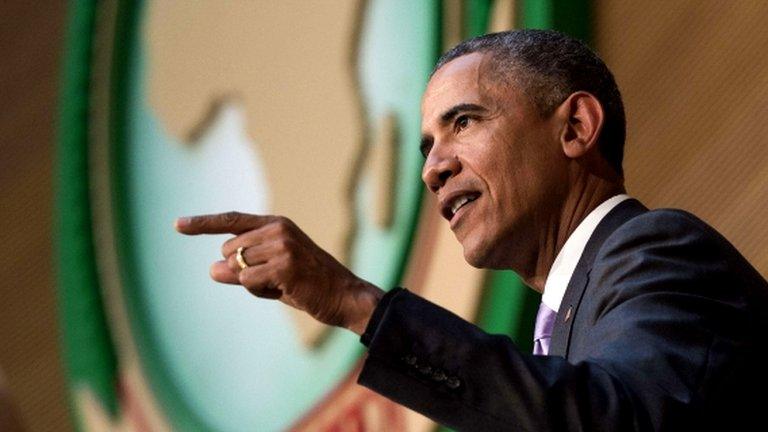

Mr Obama made it clear that such a partnership demanded recognition, dignity and respect.

He argued that, in return, African nations needed to embrace the principles of equality, meritocracy and opportunity for all. Even if at times it grated with "the old ways of doing things" or challenged traditional beliefs.

Africa is a continent whose 54 nations are rich in their diversity. But it's a continent full of promise and contradictions.

Obama’s trip to Kenya: 12 things

Brand Africa

Take for instance South Sudan, It's just four years old, and already is paralysed by civil war.

Having a laugh? A caricature exhibition was organised on the streets of Nairobi

President Obama complained that neither of its leaders had "any interest in sparing their people from suffering" after 18 months of hostilities, following a military rebellion.

On the sidelines of meetings in Ethiopia, he sought to ratchet up pressure on regional friends to push for a peace deal by a 17 August deadline - or run the risk of international sanctions.

Yet situated across the border from South Sudan - the world's newest state - lie Kenya and Ethiopia. These two nations were deliberately chosen for this trip to showcase the continent's dynamic potential. Tantalisingly close, they represent a promise of what could be.

On global security and trade, Mr Obama delivered a ringing endorsement. Brand Africa, he suggested, is becoming a force to be reckoned with as African troops are increasingly being called upon to help settle African conflicts from the al-Shabab threat in Somalia to the brutal sectarian fighting in Central African Republic.

Stepping up co-operation with the US will be rewarded with closer intelligence ties, training and kit. And that relationship is only likely to get "deeper", the president said, as the years go by.

On trade and entrepreneurship Mr Obama spoke of the "power of youth", urging leaders in both countries to create opportunities for young people to build on the economic progress achieved thus far.

With a demographic time bomb ticking in the background, he knows that millions of youths without jobs is not good for the economy and not good for peace.

Uncomfortable messages

Successful Kenyan businessman Vimal Shah, whose quiet rise to the top I've observed over the past decade, told me the key message he took away from Mr Obama's visit was that Africa needed to be in the driving seat as it navigated the economic tug-of-war between China and the US.

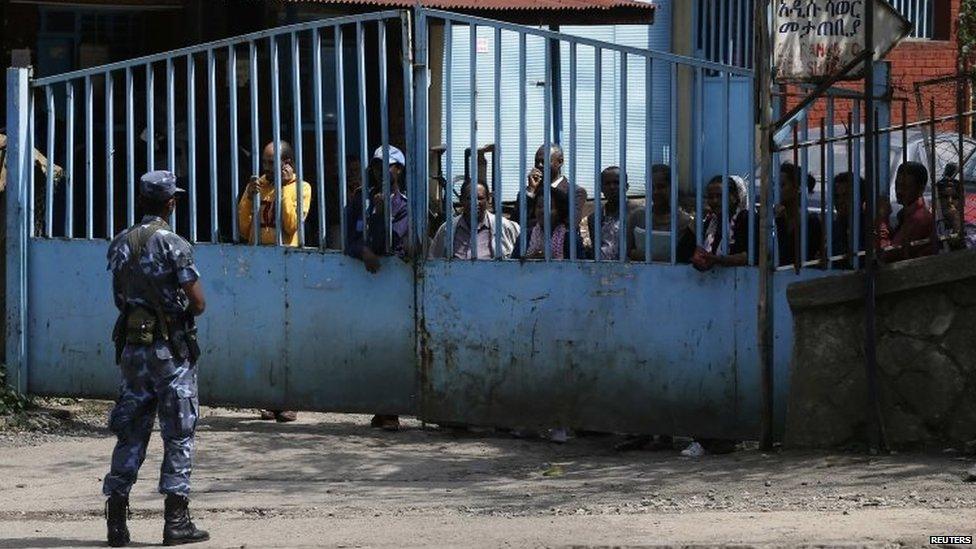

Security was raised to unprecedented levels in Addis Ababa and Nairobi during Mr Obama's visit

"It's important to take charge of our own destiny and become credible with governance and investment destinations," he said. He added that Mr Obama restored Kenya's "can do" philosophy.

But the US president also used the Africa tour as an opportunity to deliver some uncomfortable messages. Conspicuous by their absence were many heads of state at the Chinese built African Union headquarters in Addis Ababa - maybe that was just as well.

In what was the strongest performance on tour, the president seemed like a man with nothing to lose. With just a little over a year in office to go he knew he could perhaps be more bold, despite diplomatic difficulties he would have to navigate carefully.

They included accountability in Kenya, with Deputy President William Ruto still facing charges at the International Criminal Court.

And in Ethiopia, worries about the erosion of democratic freedoms, following elections earlier this year and fears about the jailing of journalists.

By speaking out so openly ordinary people may feel "empowered" by Mr Obama's speech, given permission almost to do the same - especially in countries where freedom of speech is not guaranteed.

So when Barack Obama told the Ethiopian leadership that political opponents should not be branded as terrorists and critical journalists should not be jailed, my taxi driver sat up and listened. And so did millions of others, no doubt.

He did it before in Nairobi. When he warned that "corruption is tolerated because that's how it's always been done", Kenyans paused.

Like an indiscrete guest at a posh dinner party, Mr Obama laid it bare. Yet with every word of criticism came a gesture to lessen the blow.

The US president cited America's current struggles with race and the debate over the confederate flag to show that in his country, too, they still faced challenges with democracy.

And his words of censure were offered "as a friend". Not as an outsider standing in judgement.

'Talking shop'

So, for some Kenyans like Ory Okolloh, a governance and tech specialist well known for her contribution to national debates, Mr Obama's frank talk was refreshing.

In Kenya, many local residents welcomed Mr Obama's visit to his ancestral home

And the president's African tour, with all the promise and potential it inspired, reminded her "of what we could be when we are at our best".

A good many Obama watchers had feared that the fight against terrorism would eclipse the hard messages for good governance during the the president's farewell Africa tour.

They feared his visit would somehow give credibility to badly run states.

But Mr Obama pulled no punches, when he accused presidents of outstaying their terms, and cited Burundi as an example of leaders feeling "they were above the law".

But rights groups believe the "real test" of Mr Obama's visit will be whether policies change long-term.

"If not," says Leslie Lefkow, deputy Africa director of Human Rights Watch, "then Obama's visit may have simply endorsed the leadership of two countries" which she describes as having "worrying human rights situations".

That's where strong institutions could step in.

Mr Obama made it clear that America would not be a lone voice rebuking its African friends when they strayed from the path of democracy.

He said he expected African leaders to do the same, through the African Union. For many years it's been slammed by critics as being nothing more than a "talking shop".

Perhaps the test of its mettle will be how it responds to the pressing troubles in South Sudan.

- Published28 July 2015

- Published23 July 2015

- Published24 July 2015

- Published21 July 2015

- Published23 July 2015

- Published6 July 2015

- Published22 July 2015

- Published17 July 2015