When is it hunting and when is it poaching?

- Published

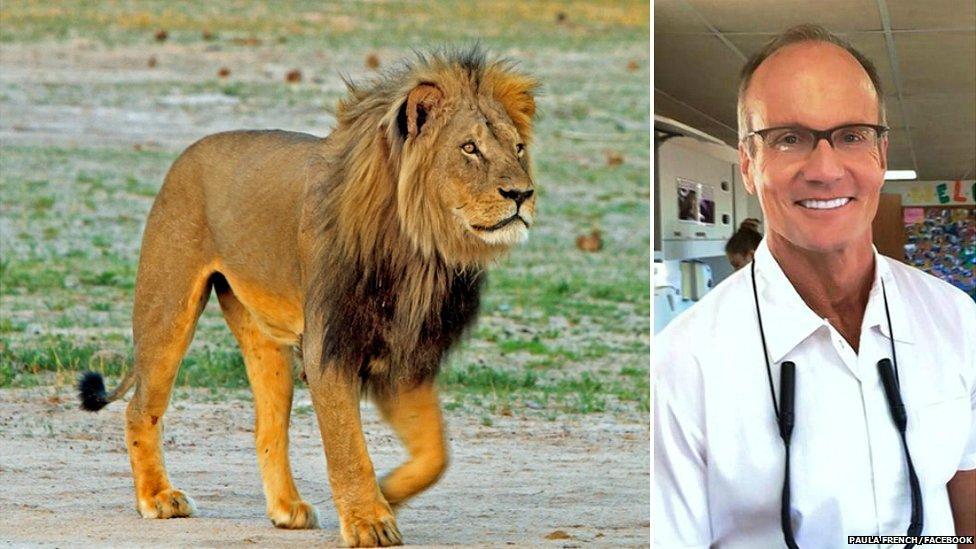

Cecil was a major tourist attraction at Zimbabwe's Hwange National Park

Cecil the lion was a renowned figure in Zimbabwe's Hwange National Park.

Earlier this month, however, American dentist Walter Palmer paid roughly $50,000 (£32,000) for the chance to kill the popular animal, although he says he was unaware of Cecil's fame and reputation.

That prompted revulsion from many on social media, with tens of thousands signing a petition calling for Cecil's killer to be brought to justice.

But what is the difference between hunting an animal and poaching?

What is poaching?

The crucial distinction to be made between poaching and hunting is where each sits in the eyes of the law. Put simply, poaching is hunting without legal permission from whoever controls the land.

Hunting lions is not prohibited per se in Zimbabwe, and indeed in many other countries in Africa. Hunting is regulated by the government, and hunters must obtain permits authorising them to kill certain animals.

Walter Palmer, who killed Cecil, said he had no idea the lion was a "local favourite"

Tourists who wish to hunt in the country may do so. Where and what they hunt, and what type of weaponry they use, is all the subject of regulation.

Foreigners hunting in Zimbabwe must be accompanied by a licensed professional hunter, and tour operators which sell hunting packages to tourists are regulated by the government.

Browsing online, it is possible to find package hunting trips in Zimbabwean game reserves for around $50,000 - about the same amount Mr Palmer says he paid for the hunt which has earned him global infamy.

The dentist who has attracted numerous unwanted headlines over the last couple of days, has insisted that he believed "everything about this trip was legal and properly handled", prior to killing Cecil the lion.

Why do people poach?

Some animals, such as elephants and rhinos, attract poachers because selling their tusks can prove extremely lucrative.

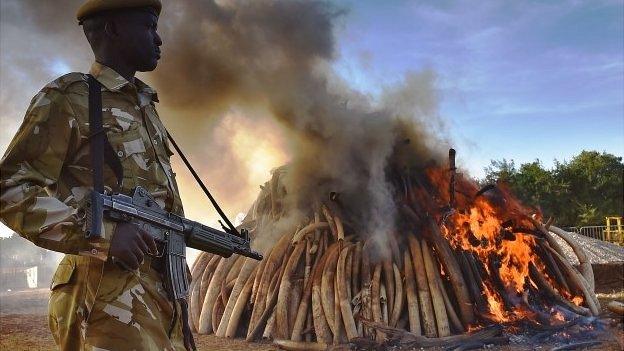

Earlier this year, Kenya's president set fire to a pile containing 15 tonnes of seized elephant ivory with an estimated value of more than $30m (£19m).

Uhuru Kenyatta lamented that the tusks had been taken from elephants which had been "wantonly slaughtered by criminals".

Rhino and elephant tusks are routinely exported to Asia, where ivory is used to make ornaments, and in traditional medicines.

For some, like Walter Palmer, however, the act of hunting itself is the attraction. That, and the prospect of a "trophy", such as a lion's head, after the kill is made.

Since he acknowledged having killed Cecil, photographs of the hunter with the carcasses of other animals have been widely shared online.

He has expressed regret that "my pursuit of an activity I love" had resulted in the death of such a popular animal.

It is estimated that more than 650 lion carcass "trophies" are exported from Africa each year.

What are the effects of poaching?

The main argument against unauthorised hunting is the effect it has on the numbers of animals living in the wild.

The level of public outcry when a case such as the slaying of Cecil the lion comes to the fore is accentuated by the fact that poachers often target some of the planet's most impressive and treasured creatures.

The Born Free Foundation estimates that between 30% and 50% of Africa's lion population has been wiped out over the course of the last two decades. Just 32,000 of the animals remain in the wild.

Can hunting have a positive impact?

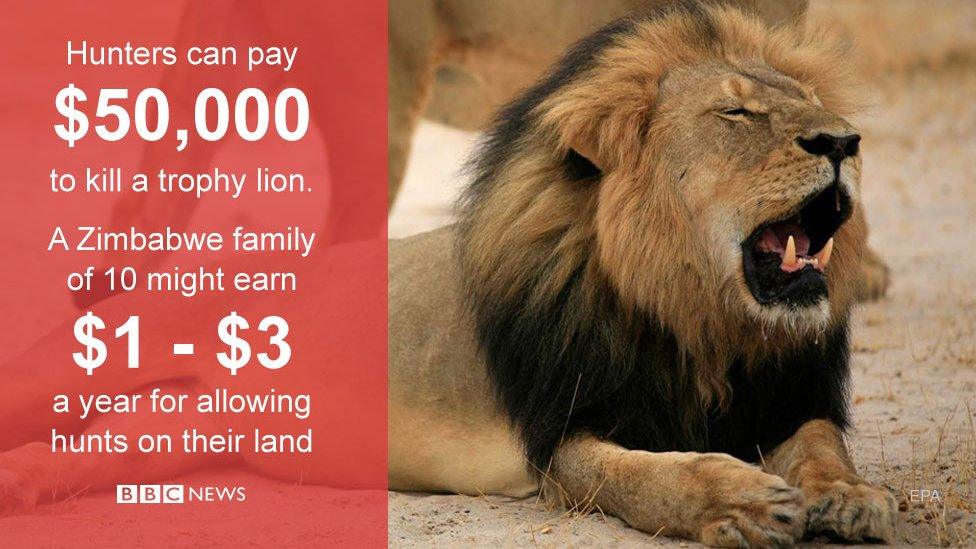

Hunting big game in its natural habitat is undoubtedly an attractive prospect for some tourists - and something many are willing to pay tens of thousands of dollars to experience.

Emmanuel Fundira, president of the Safari Operators Association of Zimbabwe, has described Cecil's killing as a "tragedy" for tourism in Zimbabwe.

Critics say the money paid by trophy hunters rarely reaches those most in need

However, he is in favour of hunting, providing it is done, as he puts it "sustainably".

The money paid by big game hunters can be used for conservation, and employs locals who otherwise may have become poachers. Wild animals inhabit the same land as locals, so in some cases numbers need to be kept down to protect lives and livestock.

Mr Fundira says tourism, of which hunting is a part, contributes "close to 15% of gross domestic product" in Zimbabwe.

But critics say that while tourism is a key revenue generator in many of the areas where hunting is common, less than 0.5% of the Zimbabwe's GDP comes from trophy hunting itself, and that the benefits often fail to reach ordinary Zimbabweans.

- Published3 March 2015