Zimbabwe's triumvirate retains firm grip on power

- Published

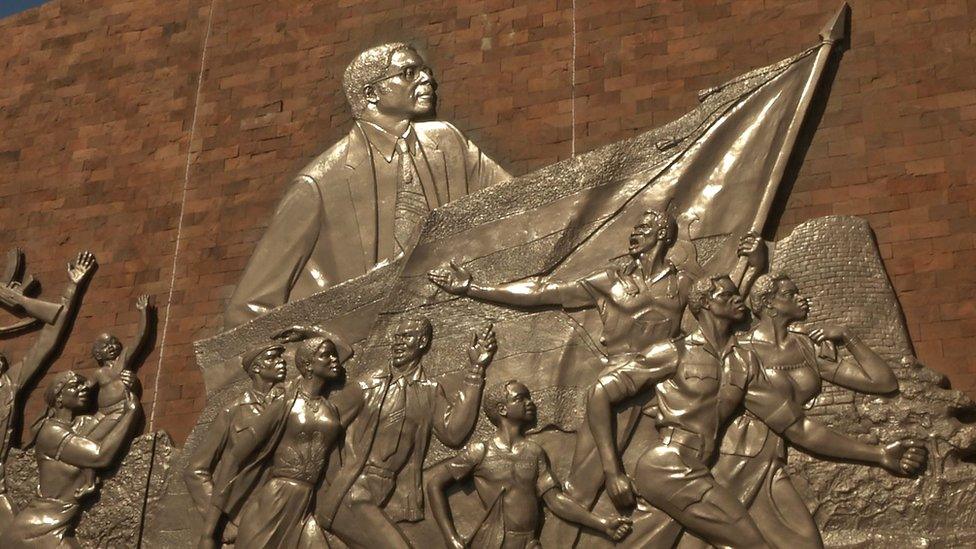

The huge golden statue of three liberation soldiers - two men and a woman - form the centrepiece of Heroes' Acre, the monument to Zimbabwe's fallen.

Alongside them in the shade of a small tent adorned in the colours of the ruling party sit two men and one woman, in whose hands the future of this country are held.

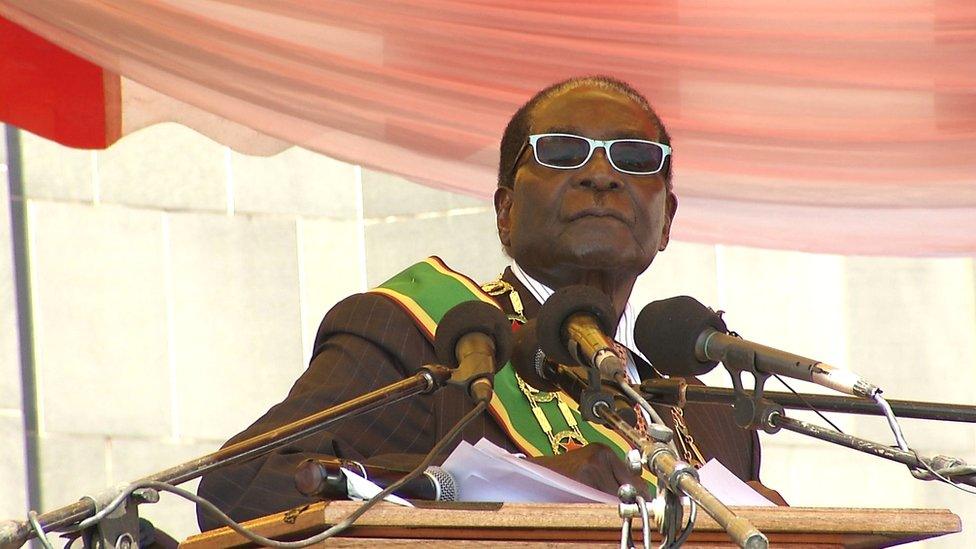

Front and centre is the man who has led Zimbabwe since the struggle for independence ended in 1980.

President Robert Mugabe is 91 years old, has been in power for 35 years, but still oozes energy and passion addressing his supporters and his nation for more than an hour in the midday sun.

He may be slower on his feet, but he's still sharp in his mind.

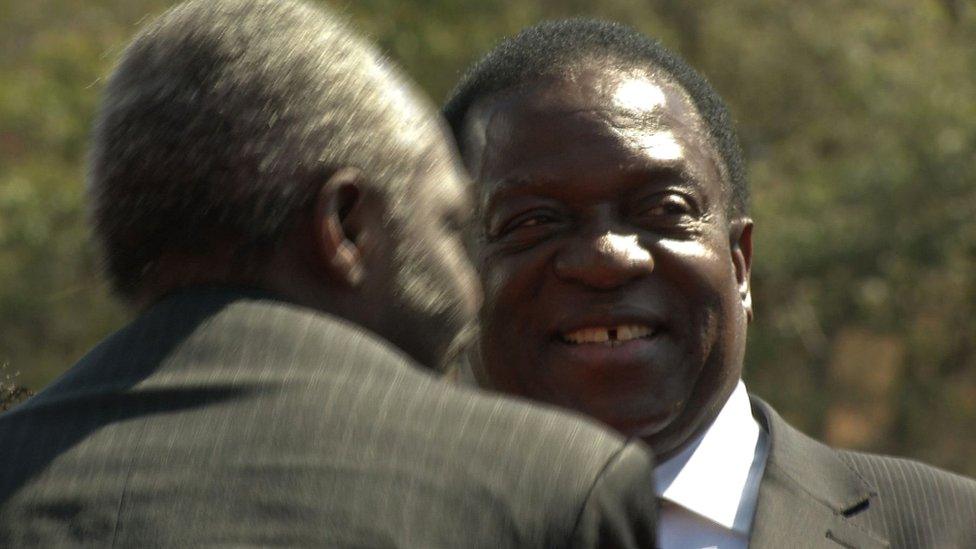

To his left, Grace Mugabe, his second wife and the country's first lady; to his right, Vice-President Emmerson Mnangagwa, the man who could be king.

Since the beginning, Robert Mugabe has dealt ruthlessly with his political rivals and outmanoeuvred those presenting any threat to his leadership.

Anyone perceived to have too much power has their wings clipped, or as happened last year, is simply blown out of the sky.

Joice Mujuru was the vice-president - the one who sat next to him under the tent at the previous Heroes' Day address.

She was an heir apparent who apparently became too much of a threat.

Hers really was a fall from Grace as the political purge enforced by Mrs Mugabe cast the vice-president and her huge support base out of the Zanu-PF party.

Now the man known as ngwenya, the crocodile, is back in the driving seat, 10 years after he suffered a similar fate.

Emmerson Mnangagwa may be someone the international community can do business with

"The nickname of the crocodile is very appropriate for Mnangagwa as he has this reputation of lurking just below the surface and only striking when the moment is apposite," said Derek Matyszak, a senior researcher with the Research and Advocacy Unit in Harare.

"The fact that he accepted… the vice-presidency would lead some people to think, well he thinks this is the right moment to be there."

First lady's future

But what of Grace? Does the first lady have presidential ambitions?

"Grace has been trying to increase her political capital in her own right, probably as a defence mechanism for when Mugabe does depart the scene," he said.

"That, I think, has been misinterpreted to some extent to suggest that she has presidential ambition."

After a period of growth during a government of national unity, Zimbabwe's economy, its currency pegged to the dollar, continues to fall as investors shy away.

More than 80% of the government budget is spent on civil service salaries, and companies are laying off workers after a court ruling lifted the requirement to pay off sacked employees.

President Mugabe publicly opposes the decision and used his speech to promise parliamentary action to put this right, but the party of the people knows the civil service expenditure is unsustainable and it's tempting to take advantage.

Heroes’ Acre is the monument to Zimbabwe’s fallen

In central Harare, the trading spaces are taken up with second-hand clothes and shoes.

Among them are a former banker, who is just trying to make ends meet.

"It keeps me going," she says. "Most industries are closing at the moment, so unemployment is a bit high, but if they open up industries, I'm sure things will improve."

And a computer science student was optimistic she'd find work when she graduated.

"You have to be creative enough," she said. "Like right now, selling these things - it's entrepreneurship - so for me it's cool."

The government has threatened a ban on pavement thrift stores, and some traders were forced away to stalls outside town a few weeks ago.

They've been labelled an eyesore, or unhygienic, but the informal economy doesn't generate tax receipts for the government, and with money short, people aren't spending in the shops.

"It's rugged my friend. The economy… it's not going anywhere, it's stagnant," says a taxi tout in an American football shirt.

"I'm a qualified accountant, but there's no jobs, you can't find employment anywhere, so I don't know what to do."

Mr Mugabe tried to be reassuring in his speech about the state of the economy

In his speech to the nation, President Mugabe admitted: "We are still grappling with the task of transforming our economies," but he tried to reassure people things were on the up.

There were certainly plenty of tourists at Victoria Falls and the Hwange National Park last week, and Zimbabwe still sits on precious metals and diamonds, but foreign investment is the key and confidence is low.

The economic ideas of Emmerson Mnangagwa and his close ally, Finance Minister Patrick Chinamasa, are already impressing Western institutions and those too nervous to invest while the old man prevails.

His ambitions for open democracy may not be as advanced, but the right-hand man may be someone the international community can do business with.

But President Mugabe, leaning on his lectern as he delivers his speech, is a difficult man to read.

After all these years, it's hard to see him settling on a successor and handing over power, unless he's thinking about his family and the political exposure they could face if he died in office.

Opposition hope

The opposition takes the purge of Joice Mujuru and the internal split in Zanu-PF as a sign of some hope, but it may have had the opposite effect and made a cleaner succession much easier.

Morgan Tsvangirai: "You give people hope there is a democratic alternative"

They are arguably even more divided and unprepared to challenge for power, after losing unfair elections and then failing to gain from a unity government.

The cult of personality wins votes in Zimbabwe, which explains why Morgan Tsvangirai still leads the Movement for Democratic Change and holds hopes of one day being president.

After 15 years of trying, he's still passionate in his words at least.

"We are not waiting for him to die," he said. "We have always done what we believe every struggle should do - you mobilise the people, you re-energise the base.

"You continue giving people the hope that a democratic alternative is a possibility."

But the strength of those on the podium, alongside the huge golden statue of liberation heroes, still hold the future of this country in their hands.