Lamine Diack: What has he achieved as IAAF chief?

- Published

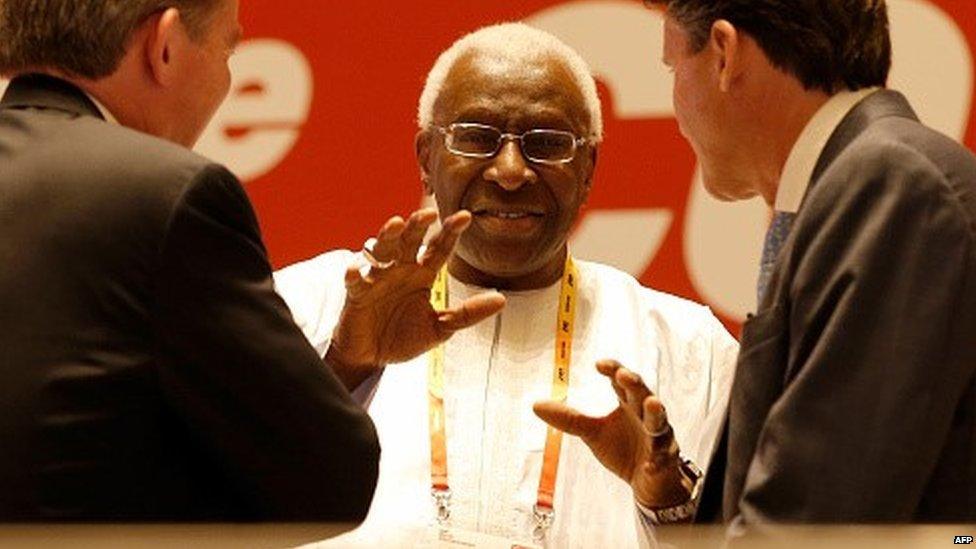

Diack believes he is leaving the IAAF in good financial shape

Senegal's Lamine Diack will formally end his 16-year reign at the helm of athletics' governing body, the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF), on 31 August.

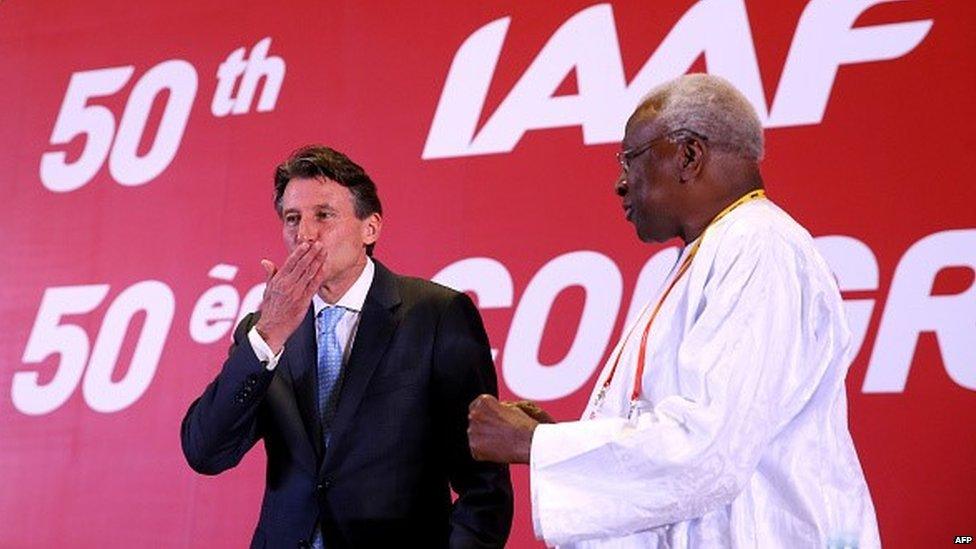

He will hand over the baton to Lord Coe of Britain, who will become only the sixth man to lead the IAAF in its 103-year history.

Diack, now 82, was vice-president when his predecessor Primo Nebiolo died of a heart attack in 1999. After becoming acting president, he went on to stand unopposed in four subsequent elections.

A former long jumper whose 1960 Olympic dreams were dashed by injury, he has been involved in athletics for most of his life - but what is his legacy as IAAF president?

Unfortunately, his departure could not have come at a worse time, given that he leaves an organisation fighting for credibility in the face of incessant doping allegations.

'Greatest gift'

Earlier this month, German broadcaster ARD and the UK's Sunday Times newspaper claimed that between 2001 and 2012, a third of medals in endurance events at the Olympics and World Championships were won by athletes who recorded suspicious blood tests.

Lord Coe will be the sixth man to lead the IAAF

On Monday, the IAAF was then forced to deny it had vetoed publication of a report that suggested that 29% to 34% of athletes at the 2011 World Championships had knowingly doped.

So it spoke volumes when one of the first pledges made by Coe upon his election was to protect clean athletes and rebuild trust by maintaining a "zero tolerance to the abuse of doping in my sport".

Nonetheless, Diack has preferred to focus on the positives when questioned on his legacy in recent weeks.

His proudest achievement appears to be vastly improving the IAAF's finances, so building on the presidency of Nebiolo, whose at-times controversial reign coincided with the establishment of the biennial world championships and a lucrative grand prix circuit.

"Long-term financial security ... is the greatest gift I can pass on to my successor as president," he told AFP in an interview this week.

Another area that will please the Senegalese is his success in making athletics universal, which wasn't the case when he joined the IAAF in the 1970s.

Lord Coe on the challenge to shape athletics' future

The first World Championships, in 1983, attracted 154 countries, whereas 207 nations will be in Beijing for Saturday's showpiece event.

The grand prix have also grown, morphing into the Golden League (1998-2009) before becoming the Diamond League five years ago - with the stated aim of taking athletics outside Europe, with Asia, the Middle East and the US all on the list of venues.

Interestingly, Diack did admit to the lack of a proper bidding process when the IAAF largely bypassed convention in April by awarding the 2021 World Championships to the US for the first time.

"Blame it on an old president on the eve of his departure who wanted to give this opportunity to the United States," said a man who has long wanted to spread athletics in the US.

That aside, and to its great credit, the IAAF has been ahead of other sports bodies in terms of paying out equal prize money, but critics have questioned the Diamond League's ability to transcend athletics.

'Cheats'

Among the laudable creations under Diack are the relatively simple, such as the Kids' Athletics initiative (which reached 1.5 million children across 100 territories in the first six years of its existence), to the very complicated, namely the war on doping.

Kenya's Rita Jeptoo has been at the centre of doping allegations

Ironically, the IAAF has often been at the forefront of the war on drugs.

The organisation was one of the first sports bodies to implement the Athletes Biological Passport, as well as the storing of blood samples to use for re-analysis in future years (when the science has caught up with the cheats).

But these anti-doping actions have now been used against the IAAF and Diack, who has given the allegations short shrift (despite admitting to a 'crisis' in the past) and highlighted a host of initiatives instead.

But as the questions abound about the way in which the IAAF publicises its findings or doesn't - for the critics who say the IAAF fears it would damage the sport by so doing - Diack is seen as the man who has allowed the stench to come about on his watch.

Not that the former mayor of Dakar sees it that way of course, believing his sport is handling the problem.

"I have said on many occasions that when the day comes where we no longer can believe what we see, then sport is dead," he was quoted as saying this week.

The problem for Diack as he leaves the highest position in athletics is that too many believe that day has already arrived in his beloved sport.

- Attribution

- Published19 August 2015

- Attribution

- Published5 August 2015

- Attribution

- Published9 August 2015

- Attribution

- Published9 August 2015